See You in the Emergency Room, Part One

Nothing goes with dry ink like cold beer, but what happens when the beer dries up? When I broke my leg on a German parking lot in 2004, I was on my way back to Paris to see a woman I’d met after a poetry reading with Geoffrey Cruickshank-Hagenbuckle at Shakespeare & Company. She had the same name as one of the main characters in a novel I had just finished writing, a coincidence which in my altered state—hair-triggered by tepid Leffe and the song “The Ghost in Me”—seemed powerfully tarot. I’d poured everything into the novel, my girlfriend and I were through, I was thousands of dollars in the hole and no one one would publish my poems, but it didn’t matter. I was going to reverse all losses with this book. This was going to be the book that paid me. I was going to float out of the humdrum, bullshit world of underground poetry on this classical, funny, truthful work of art. This is where I woke up after poetry ran me off the road. When all the poetry is gone, you can’t run up debts at some free-verse bank against some future watershed. You either do something that makes sense (like read a lot and eat square wheels) or, if you can’t stop writing you write a novel. You’ve never read mine and I bet you never will, since I destroyed “the only copy” in 1918.

The bus was parked in Germany but it was full of Poles since I was leaving Poland where I’d visited my friend Marcin Radziminski and watched a full lunar eclipse over Warsaw. That was the last time I ever saw Marty, clacking his crutches together over his head as my bus pulled out of the terminal for the most nightmarish 18 road hours I’ve ever logged. Marty had blown out both knees and shattered his shoulder in the space of a few months—not all at once, mind you, like in some spectacular accident—no. He’d done it over time, disaster by disaster, crushed bone trumped by torn cartilage, doing heroically idiotic things like skiing into a ditch on his way to help a kid in his ski class or stagediving off a retaining wall the night that Poland was officially admitted into the EU. To add to his grinning misery, meeting me off the bus in Warsaw he was carrying a hand-me-down car battery in a backpack—and when he finally took a load off, it leaked acid all over his old friend’s wood floor.

This friend had been a very old woman whom Marty had been taking care of and who had died a few months back in her bed. Marty found her sitting up with her petrified hand stretched out, almost pointing. The twin bed was gone but there was a reverse shadow of its outline on the floor. When she died, Marty inherited the flat, but he wasn’t living there and there was no furniture except a kitchen table with a few chairs, and a small dresser with a triple beveled mirror hung with the woman’s necklaces in the other room. I slept on a couple of blankets on the floor of that room, its windows scraped by the branches of a tall blossoming tree.

The battery was supposed to go into a red sports car, belonging to Marty’s imaginary friend, that was parked on a sidestreet behind the Soviet-era apartment complex (drained-aquarium-green) so he could take me to a region of Poland abounding in lakes. This did happen. We spent a night in the house of a young man up there—in his lodge—who was a bonafide hunter, a member of the Polish haut-bourgeoisie and an admirer of George W. Bush: just another beady-eyed head mounted on the wall. But for some reason, the only place he had for us to unroll our sleeping bags was on the floor of a small kitchen in back—the old servants’ kitchen, I suppose, and we were told that we had to leave before daybreak: The man and his hunting party intended to get an early start.

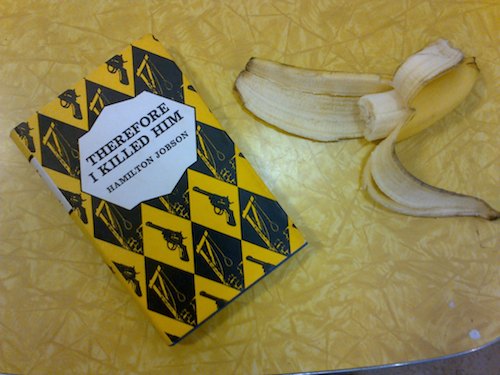

On a side note, I sometimes wonder if I’m taking it too seriously, this poetry thing. It’s on my mind both day and night. When I can’t sleep, I make poets jump over a fence. I’m like a white supremacist, only instead of hate I thrive on the glory of poetry. Instead of hair clippers, I curl up with my chapbook collection. I text Filip Marinovich every other day with new poetic findings: “Wm Wordsworth a GREAT POET.” I confess that I’m not a very deep reader. Regularly on this blog and elsewhere I come across the names of poets from all over the Americas, poets who chanted their poems out loud to thousands at once and who may have even died for poetry. Not one name rings a bell. Even as I demand originality from others, I rationalize my ignorance in all of the usual ways. I’ve always wanted poets to blow me away. I want the poem to kill me, to make me feel simpatico with the poet behind it. So begins the revolution: thirty feet below the lab, on a dirty mattress in a steam tunnel. In the same way that, as a kid, my heart would start pounding when I came to the little ad for x-ray specs at the back of the comic book—because I wanted to see inside of dogs—when I pick up a new book of poems by a mysterious poet my heart skips a beat. I even get cottonmouth. Oh man, do I want it to be good—amazingly, obliteratingly good. And at the same time, how relieved am I when it’s no good at all? When I can say, while sliding the book back into place, “Very smart. Of course, I came here to be immersed in a tub of gelatinous morphine spiders, but all the same...”

Julien Poirier grew up in the San Francisco Bay area and was educated at Columbia University. He is ...

Read Full Biography