“Always Being Myself”: Remembering Alice Notley

She survived in and because of poetry. That, and love.

Essays in the “Remembrances” series pay tribute to poets who have died in the past year.

“I will never leave you. I can’t explain what I mean or who you are.”

Alice answers the door, one flight up, her name in lithe cursive taped to the buzzer. She’s small in the entrance of her small apartment, which is the smallest here. We hug. I take the pastries I’ve brought into the kitchen—she likes apple pastries the best—where I cut them in half, as equally as possible. She is judicious about the sharing of pastries. We are settling into another day of organizing and remembering and gossiping and preparing her archive—a project we’ve been working on together the last few years. Alice orders me to sit down as she makes the coffee. “Do you want a single or double?” I usually want a double.

With stacks of papers and boxes between us, she sits in her blue chair and tells me about a dream she had the night before, in which she was absorbing folders of typescripts into her body: “They were so soft!” I sit at the table—the same one she’s made collages at, for years—as I sort through those folders, and use an app on my phone to scan over 6,500 pages of typescripts and manuscripts, much of it unpublished. Also, correspondence, notebooks, artwork, photographs, and large collections of work by both of her late husbands, Ted Berrigan and Douglas Oliver.

Mostly I show her things and something wonderful happens. I hand her a page from an extended manuscript of Parts of a Wedding, from the mid-1980s, with a green-and-blue-colored drawing of a planet cut in half, one side labeled “A” and the other “10th,” a kind of cosmic diagram of the East Village street corner that appears in her poem “I The People.” “Did I make that?” she says, baffled—then, “Ah, yes. I was being Charles Olson as myself.” This process, repeated many times, becomes a kind of ritual.

Other times, a vortex opens—residue of Alice’s losses. She shows me a series of poem-postcards made in collaboration with George Schneeman after Ted died and says, “You are the first person I am showing these to.” “Ever?” “Yes.”

She remains hilarious and full of refusal. I read out loud from a paper she wrote in high school on Walt Whitman that begins, “I have a basic, irrational prejudice against Whitman which has nothing to do with the quality of his poetry.” “I was always,” she says in response, “being myself.” She shows me her most recent notebooks, explaining it will be a book called The Old Language. “It’s what I’ll be writing until I—” she stops. “It is what I’ll be writing for the rest of my life.”

She asks about my family. She makes statements about my destiny. On one of our last nights together, she makes me shrimp alfredo. She says, “You’ve done so much for me.” There is a density to our work here, cut through with intimacy and grief, and the apartment becomes saturated. The vortex touches us both.

Once, she emerges from the bathroom and announces, “I went into the bathroom and became very thoughtful.” The way she says “thoughtful” makes it sound like two words: thought full.

I find a typescript of a poem called “Needles, California” dated “7/30/86.” It’s the day my wife Carrie was born. The poem is sort of occasional, complete but unpublished, and includes the words “picante sauce,” which delights me. Alice reads the poem out loud to me, an acknowledgement of love and its proximities. She cares about me. Our lives are entangled.

She just

wants you to

do right, for love & a little comfort

I want

you to be a coldhearted poet, with me.

I keep, as an amulet, the staccato shape of her voice in those last lines.

Alice tells me things about loving her husbands and how they loved her. I absorb, softly, as much as I can. I will think about these things for the rest of my life.

***

“the people I’ve loved and who died are still free inside themselves, uncharacterized and unchronologized by me or anyone.”

Alice survived in and because of poetry. That, and love.

She also thought a lot about time, timeliness, and timelessness, which have to do with different ways of considering poetry’s forms, but she refused linearity, which did not reflect her experience of art and of life. Because of this, her poetry carries the capacity to be instructive about, and to participate with, death and the dead. She wrote books with titles like When I Was Alive, Alma, or The Dead Women, and Grave of Light. At a conference on her work a few years ago she asked, “What can we learn from the fact that we don’t die?” She was suggesting that death is the state of becoming the substance of communication—that therefore we continue to have a form but not matter—and what does this mean? At the same gathering she tossed off the incredible statement, “Sometimes I think my entire oeuvre is a response to As I Lay Dying.” She was funny like that. Her inscription in my copy of When I Was Alive is simply: “to Nick, when I was alive.” (So close to “when I was Alice.”) She was funny, also, like that.

On the title page of When I Was Alive there is a small image of a black galleon ship. When I asked her about the ship imagery laced across her poetry and collages, she looked into me and recited this D. H. Lawrence couplet: “Have you built your ship of death, O have you? / O build your ship of death, for you will need it.”

Alice built her ship of death. It was everything she did. It’s like what she wrote about James Schuyler’s The Morning of the Poem: “A whole life happens right now. It’s a beautiful morning full of life and death and everything that ever happened to you.” Alice had the capacity to articulate these braided temporalities. There’s a page in her notebook from 1970—before any of the grief that circulates in her poetry has occurred—on which all that appears is the question “Where are the dead?” And in the bottom right corner, very small, is the response: “quilted.”

We thought together about her temporalities when I was editing Early Works, a book published by Fonograf Editions that collects her poems written between 1969 and 1974. She writes in the preface to that book,

Being alive are you always the same person? I invite you to this volume asserting I am still she or at least remember how I chose the words contained herein as my details, conscious that no choices were correct, but somehow the details would add up to something “true” nonetheless.

That she emphasizes “words” instead of “poems”—Alice communicated an undeniable matter-of-factness about living among words—means everything (see her essay “Because Words Aren’t Language” in the first issue of Talisman).

I have a piece of paper on which Alice wrote the word “coral.” It’s beautiful.

“I can’t explain what I mean or who you are,” she said. Neither can I, other than to say that on the cover of the notebook I’ve been using is taped a copy of a thing she made: a photo of an unnamed baseball player under which she’s written “Fuck Creation.” The elegance and irreverence of Alice’s ship.

***

“We die and go to poetry.”

A few days before she died, I asked Alice if she would make me a list of her favorite folk songs, the ones she’d sometimes sing while we worked together in her apartment. She emailed me from her hospital bed with the subject line “probably illegible” and a photo showing her open notebook with two pages of handwritten song titles. “Careless Love,” “Wild Mountain Thyme,” “What is the Soul of a Man,” “Shady Grove.” At the bottom of the image, she arranged two figurines—a blue-eyed owl and little R2-D2—to weigh down the pages. “Baby, Please Don’t Go,” “Down in the Valley,” “Spanish Johnny,” “In the Pines.” There are no musicians, just song titles—these are folk and blues songs, after all—all written in her lush cursive. “Shenandoah,” “Black Is the Color of My True Love’s Hair,” “The Water Is Wide,” “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean.” This will be the last thing she says to me.

I adored Alice. Writing that sentence is bright pain. I adore her.

The last time I saw Alice earlier this year, I was in Paris for a week to pack her archive. Everything we had sorted through and inventoried during my previous visits we touched again, together, before placing it all in newly labeled folders and boxes. She deemed me “the house critic,” insisting, “I always knew you were.” She said Ted would agree.

The responsibility she trusted me with was immense and gratifying. It was also a demanding, exhausting experience, physically and emotionally, for both of us. She was managing shifting and unusual pain following an operation and wasn’t recovering the way she’d anticipated. We worked 10 or more hours a day, rarely leaving the apartment. Walking had become more difficult for her. We were tired. We ate a lot of pizza.

Sometimes, as we went along, I had the feeling Alice was encountering an object for the last time. A mimeographed copy of Berrigan’s The Sonnets with her own, original cover painted in yellow, red, green, blue, and black watercolors. The collage with a childhood photograph of her in the middle that appears on the cover of Grave of Light. A 1981 birthday list asking for, among other things, “whatever the works are of Jane Ellen Harrison,” “batteries for my fuckedup radio,” and “garnets; notebooks; watercolor sets; inks; watercolor pads; herbs; a tea chest; tights; bath salts.” I don’t know what she felt as these things, and years more of it, were packed and secured, reoriented from being the material stuff of her life into this archival collection. Often, she would finish sorting through something, let out a long sigh, look up at me, and smile. I think she was happy, mostly, especially to see what she had of Ted’s and Doug’s preserved alongside her own legacy. She had maintained what she called “this record of continuous practice,” and could see it on to its own afterlife.

Before I left that last night, I took a picture of Alice in her blue chair looking over at our stacks of boxes. She rose to hug me and, standing on her tippy toes, kissed my cheek. It was raining in Paris outside her small apartment.

Then, a few weeks later: “Dear Nick, …. I have to go now. I love you.”

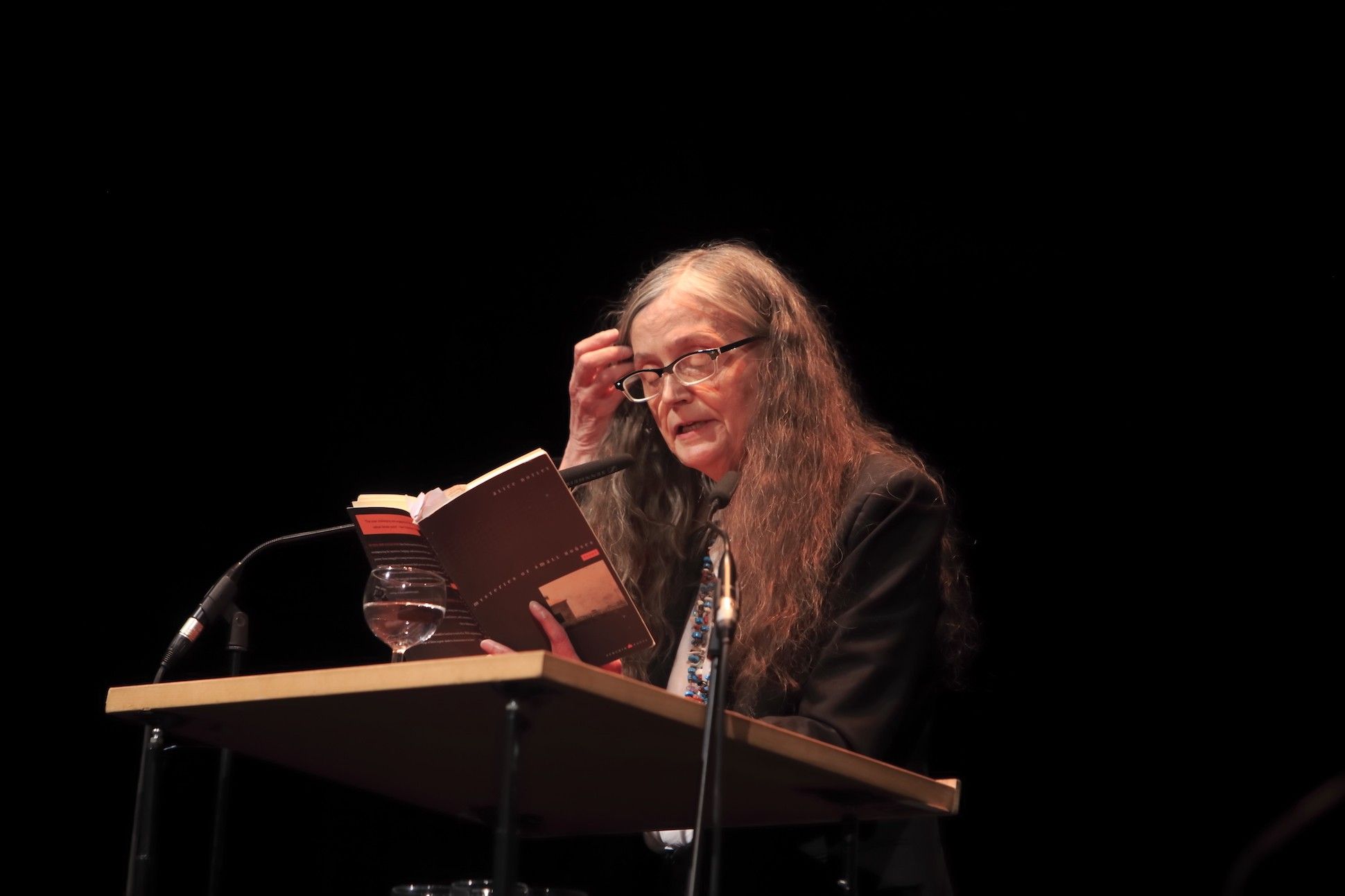

The author with Alice Notley on her 77th birthday, November 8, 2022.

Nick Sturm is a lecturer in English at Georgia State University. He is a co-editor of Get the Money!: Collected Prose, 1961-1983 by Ted Berrigan (City Lights Publishers, 2022) and editor of Early Works by Alice Notley (Fonograf Editions, 2023). His book Publishing the New York School: Small Press Communities and American Poetry will be published by Columbia University Press. More information about...