DADA at MOMA: 11 Outlined Epitaphs

At this crowded exhibit, war is never far from the picture.

Introduction

July 26, the Wednesday I stopped by the Dada show at the Museum of Modern Art for a second look, was also a day that Hezbollah fired some 130 rockets into northern Israel and the Israeli Golani Infantry Brigade attacked the Lebanese border town of Bint Jbail—a day, according to the next morning’s New York Times, with the highest death toll (so far) in the Israel-Hezbollah war. Over the following weekend a “precision-guided bomb” would explode an apartment building in suburban Beirut, killing 60 civilians, more than half of them children. Off the front pages and AWOL from CNN, casualties in Iraq still hovered around 100 every day.

In the subway on the way to the Dada show I flipped through The Poems of Emily Dickinson: “For each ecstatic instant / We must an anguish pay” and “’Twas like a Maelstrom, with a notch, / That nearer, every Day.” I carried a copy of Thomas E. Ricks’s Fiasco: The American Military Adventure in Iraq. At a newsstand on Sixth Avenue I found the latest issue of New York magazine, and later that night would read this query in Kurt Anderson’s column. “Might the Israeli soldiers’ capture turn out to be,” Anderson wondered, “our century’s assassination of an Austrian archduke. . . ?”

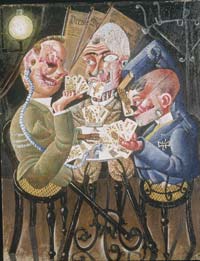

Otto Dix, German. Skat Players (Die Skatspieler) (later titled Card-Playing War Cripples [Kartenspielende Kriegskrüppel]). Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. 2006 Nationalgalerie. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin-Preussischer Kulturbesitz. Otto Dix, German. Skat Players (Die Skatspieler) (later titled Card-Playing War Cripples [Kartenspielende Kriegskrüppel]). Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. 2006 Nationalgalerie. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin-Preussischer Kulturbesitz. |

“But what can I do?” as Lesley Gore sang in “Maybe I Know.” Dada was an emergency, in the form of a response to an emergency. “How can one get rid of everything that smacks of journalism, worms, everything nice and right, blinkered, moralistic, europeanized, enervated?” Hugo Ball, the erudite instigator of Zurich Dada, challenged in a 1916 manifesto. Ball’s answer? “By saying Dada.”

“Saying Dada” ultimately embraced a complex of slippery, contrary notions and lots of devastating, gorgeous, irreconcilable artworks. But as Raoul Hausmann, an artist out of the aggressively politicized Berlin Dada, once proposed, “In Dada you will recognize your real situation.” For many of the strongest Dada figures, such as Hausmann, Hannah Höch, John Heartfield, George Grosz, Otto Dix, Richard Huelsenbeck, George Scholz, Kurt Schwitters, and John Covert, and even to some degree for Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, and (the Baroness) Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, “recognizing your real situation” included internalizing, parodying, and embodying the war. “The best and most extraordinary artists,” Huelsenbeck contended in a manifesto he presented to Berlin in 1918, “will be those who every hour snatch the tatters of their bodies out of the frenzied cataract of life, holding fast to the intellect of their time, bleeding from hands and hearts.” He demanded “an art which one can see has let itself be thrown by the explosions of the last week, which is forever gathering up its limbs after yesterday's crash.” Huelsenbeck’s aim, he later said, was “to make literature with a gun in hand.”

The first time I walked through Dada at MoMA, I could notice only what was wrong with the show. Some of my resistance inevitably involved MoMA—the new MoMA essentially is another expensive monument for tourists in New York City; everything about the architecture and the exhibition spaces appears calculated to propel the greatest number of casual viewers in the shortest time through modern masterpieces; and there’s no place to sit, look, and think.

But this Dada show is also a mess—the walls are crowded with too many pieces, as though the curators couldn’t decide whether they were hanging art or artifacts. There’s scant social context for the art and artists despite the emphatic six-city division, and the borders between the cities blur. Dada was a literary movement, yet the books, magazines, and broadsides are on display mainly for their art and design. Depressingly, the MoMA show displays little of the urgent majesty about Dada that you might uncover, say, in Huelsenbeck’s Memoirs of a Dada Drummer, Ball’s Flight Out of Time: A Dada Diary, Robert Motherwell’s The Dada Painters and Poets: An Anthology, or Greil Marcus’s Lipstick Traces.

But on the day I returned, these objections fell away—a war was on inside as well as outside MoMA, and I could see the art again. If you don’t enjoy Dada, you likely imagine that the art is adolescent: collage, photomontage, performance, readymades, put-ons, chance, and stunts. But for both our private and collective sentimental educations, Dada is probably everyone’s virgin avant-garde, at once our earliest personal experience of an artistic vanguard, whether smoked out in high school or college, through Tristan Tzara or Talking Heads (who recorded a Hugo Ball nonsense lyric on Fear of Music), and the common inspiration behind nearly every twentieth-century gesture that mattered, from surrealism to abstract expressionism, Andy Warhol, John Ashbery, and punk.

Here follow 11 necessary Dada at MoMA moments, 11 Dada epitaphs:

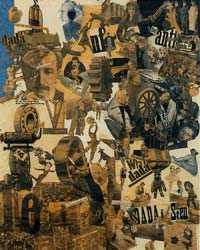

Hannah Höch. Cut with the Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany (Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser durch die letzte Weimarer Bierbauchkulturepoche Deutschlands). Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. 2006 Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin. 2006 Hannah Höch / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, photo: Jörg P. Anders, Berlin. Hannah Höch. Cut with the Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany (Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser durch die letzte Weimarer Bierbauchkulturepoche Deutschlands). Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. 2006 Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin. 2006 Hannah Höch / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, photo: Jörg P. Anders, Berlin. |

2. Certain walls, however overstuffed, are sure to make you physically feel—as Dickinson famously wrote about poetry—as though the top of your head has been taken off. I’m thinking of the Hannah Höch, Kurt Schwitters, and Raoul Hausmann walls. All these displays, surely not coincidentally, are instances of photomontage, a medium invented in the summer of 1918 by either Höch or Hausmann during a holiday to the Baltic Sea, that is, if photomontage wasn't already invented by someone else. (As Hausmann recalled, “It was like a thunderbolt: one could—I saw it instantaneously–make pictures, assembled entirely from cut-up photographs.”)

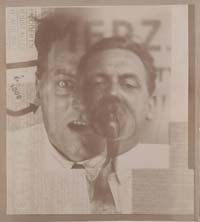

El Lissitzky (Lasar Markovich Lissitzky). Kurt Schwitters. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther Collection. Purchase, 2001. 2006 El Lissitzky / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. El Lissitzky (Lasar Markovich Lissitzky). Kurt Schwitters. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther Collection. Purchase, 2001. 2006 El Lissitzky / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. |

Poet and scholar Robert Polito was born in Boston, Massachusetts. He earned his PhD from Harvard University and has served as director of Creative Writing at The New School for two decades. Polito served as president of the Poetry Foundation from July 2013 through June 2015.

Polito’s collections of poetry include Hollywood & God (2009) and Doubles (1995). His poetry blends narrative and lyric impulses...