What’s the Story?

Tracking Narratives in the February 2015 Poetry.

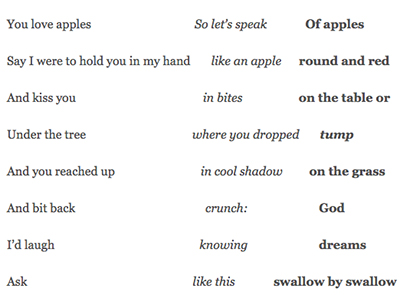

In the February 2015 Poetry, Peter Heller’s “Apples” presents a range of branching narratives, hinting at multiple stories at once and letting us choose—or even create—our own. What happens in the poem depends on how we read it:

Heller describes dropping fruit, and we can drop through his poem however we choose. Try reading each column in isolation: the first and second give us juicy love poems; in the third, God dreams of apples. Reading across the columns, line by line, joins all these visions together into a coherent narrative. It’s also possible to move from left to right, skipping up and down lines, to “write” a poem of your own: “You love apples / in bites / on the grass / under the tree / in cool shadow / of apples…” This poem invokes Edenic vocabulary and images—apples, trees, falling, knowing, God—as if to suggest that God’s creation of Eden reflects our creation, or co-creation, of poems within “Apples.”

Like an apple, this poem can be consumed “in bites,” “swallow by swallow.” The patchwork of phrases and images that comprise any of the poems within “Apples” make them similar to “dreams,” those scrambles of associations. Perhaps the poem’s formal play also mirrors love: it’s as though the various parts of the poem are romancing each other, trying to merge.

While “Apples” hints at several sweet narratives without privileging any in particular, Cate Marvin’s “Dead Girl Gang Bang” asserts a single, bitter storyline—and the title, a string of forceful syllables, tells us exactly what the story includes. Revelation of fact is a theme of the poem, which begins: “Though I can’t recall your last name / now, Howie ….” The speaker grants Howie anonymity for one line alone, and later—after giving him another, less flattering label, “balding fuck”—she elucidates what he called his victim: “sloppy seconds.” The victim eventually killed herself, and throughout the poem, Marvin repeats the word “dead”—it appears six times, not counting the title. With each reiteration, she insists more vehemently on the damage Howie wrought.

The speaker goes further than sharing her friend’s story: she nearly wills herself into her friend’s shoes. “Hell, just thinking about / it makes me wish I were dead,” she notes, and later: “Still I wear the dead / girl’s perfume. And I’ve got an accident / to report. Because it was all our centers, / uninvited, you rucked up inside.”When the speaker’s unsympathetic husband mocks her tears by calling out “We-we-we,” we might hear a pun on the second person plural (as well as a suggestion that the speaker’s male counterpart, like her friend’s, is no prize). It is a “we” who speaks here—a joint identity, consisting of the speaker and the rape victim—rather than just an “I”:

I’ve been where she’s been,and I can be where you are now, switch my hips,

sashay into your office to see you any day now,wearing her perfume.

In a subtle signal of this “switch” of identities, the speaker uses the language of courtship on Howie—she’ll sashay, switch, and perfume, and she’s “penciling [her]self in to [his] way back then.” “Every day,” she writes, “the marsupial clouds grow / hungrier for our reunion, the reunion I’ve been / packing for all my life.” In another poem, the observation would sound amorous—but here, the speaker’s language recalls romance to remind us how very un-romantic her friend’s interlude with Howie was.

What’s the effect of this fusion of identity? Might it suggest that the other girl still lives in her, as if to compensate, just a little, for her death? Might it prepare the reader to identify not only with the speaker but also with the victim, as the speaker does?

And as different as these poems are, do they have anything in common? Heller gestures toward multiple stories at once, whereas Marvin leaves no doubt as to what tale she’s sharing; she’s pointedly straightforward about a topic often evaded or denied. And yet the imaginative space of the poem allows her to hint at alternate accounts, too—accounts where she merges with her friend, or where she confronts the rapist—that render the prevailing narrative all the more powerful.