Poetry magazine's Editors’ Blog occasionally features online exclusives. This installment comes from Mairead Small Staid. Past exclusives can be found here.

In the alphabet recited by nineteenth-century schoolchildren, it followed Z. And per se and, they would say, and per se and. A logogram masquerading as a letter, a letter that is also a word—like a and I and even o, but no—a letter that is only a word, the plainest word of all. A word we could do without, to be honest, if we had to. We don’t have to, and thank the language gods for that.

&

“This isn’t the whole story,” wrote Larry Levis in “In the City of Light.” “The fact is, I was still in love. / My father died, & I was still in love.” There it is, that Levisian ampersand, if I can coin a term to mean curled like the vines he plucked grapes from in the San Joaquin Valley of his youth, tractor-wrought under the dusty sun. Soft as the spilled eyes of horses, while the words on either side kick like hooves. Two loops inseparable and yet trying to be closer still, trying to enter each other like lovers, trying to draw all around them into their maw, a black hole, gasping and cosmic. Two loops like the “handcuffs that join / Each wrist in something that is not prayer, although / It is as urgent.”

&

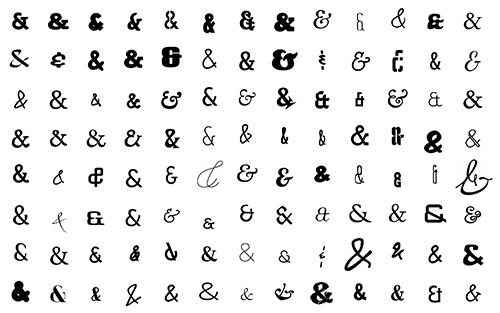

The symbol existed long before its name. In the cursive scripts of ancient scholars, the letters of Latin’s et grew together, a miniature vineyard. This history is less buried in other fonts, closer to the surface: &. &. &. &. Two letters become one, ligature, and the letters disappear; it’s like a fear of marriage. In this font, with its serifs and formality, the symbol is a funhouse S, seen in a mirror; a ribbon fallen and twisted; a small, seated person with palms outstretched in offering, or supplication. In all our many metaphors, nothing reaches like a hand.

&

More Levisian ampersands:

“someone anonymous, & too late”;

“if the dead could shrug, & they / Can’t”;

“Their limbs reach / Toward each other, & their roots must touch the dead.”

In these lines, in a hundred others, I find something akin to Keats’s negative capability (“that is, when man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact & reason”) and yet distinct from that state, even—if it is not blasphemous to say so—beyond it. I don’t think it occurs to Levis, or the speakers of his poems, that fact and reason are worth reaching after. I don’t think the notion has ever crossed their minds. Uncertainties, mysteries, doubts: these are the quarks and neutrinos of poems, from which everything else arises. I once thought the ampersand a perfect distillation of a poem that doesn’t use the symbol—this single, delicious breath by A.R. Ammons: “One can’t / have it // both ways / and both // ways is / the only // way I / want it.”

But in the poetry of Larry Levis, both ways is the only way it is.

&

From the FAQ page for the Writers Guild of America:

What is the difference between the word “and” and the ampersand (“&”) located between writers' names in a writing credit? The word “and” designates that the writers wrote separately and an ampersand (“&”) denotes a writing team.

Wikipedia elaborates:

In screenplays, two authors joined with & collaborated on the script, while two authors joined with and worked on the script at different times and may not have consulted each other at all.

&

An editor once removed forty-four ampersands from a long poem I had written. I didn’t argue, partly because the editor had gone to such trouble, all those red ands—Track changes, as if it were that easy—and partly because I couldn’t articulate why it mattered. Perhaps it didn’t. But I missed them, the gentle surprise of their presence—gone by the forty-fourth though, I suppose—and the simple prettiness of the symbol in place of the letters to whose beauty we are inured. The word made, if not flesh, something just as improbable.

If I had known of the WGA’s style guide, I might have cited its rules in my ampersands’ defense. My words have collaborated, consulted; let them be joined, a writing team. The poem, once made, cannot be divided into the discrete parts that formed it, no, it is fired as in a kiln, and to separate would be to shatter. I might have quoted T.S. Eliot, in all his exquisite snobbery: “When a poet’s mind is perfectly equipped for its work, it is constantly amalgamating disparate experience; the ordinary man’s experience is chaotic, irregular, fragmentary. The latter falls in love, or reads Spinoza, and these two experiences have nothing to do with each other…” In other words: My father died, & I was still in love. Uncertainties, mysteries, doubts: they are the particles of life, too, and we can break them down no further, not with such limited equipment as we are.

&

The prevalence of the ampersand in the wedding invitations arrayed on my refrigerator speaks, I think, to a knowledge, conscious or not, of usage rules like the WGA’s. The ampersand signifies a closeness that and merely shrugs at, makes of two parts—or people—a single unit: Dolce & Gabbana. Rhythm & blues. Andrew & Martha.

Of course, the symbol also looks like nothing so much as a knot about to be tied.

Of course, symbols are easy, next to acts. But they are not meaningless, just as failed attempts are not failures, as Levis, who married and divorced, must have known. Better the attempt than nothing. Better the ampersand, the grand gesture, the promise made, even if it will be broken, and the pretty knot untied or cut away.

&

My father died, & I was still in love. I meant to say something about how the ampersand allows unity in contradictions; about how it can weigh two conflicting options—the symbol’s palm upraised in imitation of a scale—and find neither wanting; about how, lonely thing, in need of propping up, it stands thanks to opposing forces shoving from either side. But the fact is, that line by Levis contains no contradiction. Contradiction would look like more like this: I was in love, & I didn’t want to marry, but no, even this opposition is less than diametric. Better still: I was in love, & I wasn’t.

Both ways is the only way it is.

&

In 2001, the Dutch design company Experimental Jetset set out to make an ur-shirt, an archetypal band shirt for an archetypal band. The T-shirt bore no image, only the following text:

John&

Paul&

Ringo&

George.

Originally, only the names had been listed, but the designers didn’t like how much longer the George line was than the others, so they added ampersands after the first three names. A purely aesthetic choice, and what’s wrong with that?

In the years since, hundreds of shirts have paid homage to this original by borrowing its form, ampersands included. One can find T-shirts advertising their wearer’s allegiance to other bands and musicians (Billie & Aretha & Mary J & Lauryn & Erkyah), the characters of television shows and movies (Luke & Leia & Han & Chewie), the disciples (Judas holds the ampersand-less last spot), political campaigns (Barack & Obama & Yes & We & Can), sports teams, a city’s neighborhoods, and the vague designations of a lifestyle (Shoes & Alcohol & Drugs & Boys). Many simply bear the names of friends, the shirts made, perhaps, for occasions like bachelor and bachelorette parties.

There’s a joke about reading poetry, how it isn’t difficult, how each line is only the name of a horse, the poem only a list of horses. I think Levis would have liked this joke, his poems already full of equine nomenclature: “Last Button. No Kidding. Brief Affair.” To list what you love, many-chambered as the heart; to couple one part to the next to the next, forced to give nothing up; to carry what you love, to wear it on your chest, to possess it as fully as you can—this is one reason, at least, to write poetry or to read it, those beautiful names of horses grazing on the tongue.

&

Levisian ampersands give way to Levisian ellipses, at times “when / The trees shine without meaning more than they are, in moonlight, / And when it seems possible to disappear wholly into someone / Else, as into a wish on a birthday, the candles trembling…” They gesture toward the unsaid, the unsayable, though they do not “make a fetish” of it, as Maggie Nelson said of Anne Carson’s brackets. There are no blank spaces here, only knotty brambles of nouns, ampersands tangling them together, and then the ellipses, where the wind has blown the grasses flat. Punctuation wrangles language, and language wrangles back: sometimes bucking, sometimes coming quietly along, nuzzling the halter slipped over its head. Commas alight like birds, in patterns I cannot predict and yet find beautiful, the way one lets me catch my breath, offering it—my own breath—to me like a gift, the way another’s absence takes it away. And when periods come, they come like the death of one once loved, far away: sudden and mournful and then gone from the mind, to be remembered again and again, each time as terrible as the first. Things end. This fact is impossible and all around, reading Levis, his poems that are really only very beautiful lists of what he has loved. Dot, dot, dot. And, and, and.

&

Levis doesn’t use ampersands in his first three collections, doesn’t introduce them until 1985’s Winter Stars. I could say something about time growing more urgent, more immediate, something about the solace and speed of the ampersand—but it’s getting late, and I don’t know. I will only say that words slur—and per se and—and change as we do. We grow unrecognizable to the people we once were or knew or to the parents who bore us, whom we once resembled but no longer, a ligature disguised by time.

Or perhaps we resemble them even more so. Perhaps we recognize ourselves only now.

&

It’s not that fact and reason don’t belong in these poems, but they hold no rank higher than the fictions and feelings they stand alongside, shoulder to shoulder. Offering or supplication, the palm opens just the same. This isn’t the whole story. It never is: this doubling back is the advantage poetry holds over life: it can contain both what we did and what we wish we’d done, what we reveal and what we’d rather hide, all those ifs and if onlys. “It happened otherwise,” Levis wrote, but that doesn’t negate the lines—lies—he’d just written, and printed, and meant. His poems are like the errata sheets inserted into old books, after publication: admitting wrongness but refusing to erase it. Accumulating—and, and, and—without apology.

“In the City of Light” ends with several openings, a many-hinged door:

There are two things I want to remember

About light, & what it does to us.Her bright, green eyes at an airport—how they widened

As if in disbelief;

And my father opening the gate: a lit, & silentCity.

There are two things, he says, and a poem is titled, a few pages later, “There Are Two Worlds.” But how to move between them? How to hold them close? Both ways is the only way, after all. Things at odds—My father died—are equally vital—I was still in love—and how could he, how could we, ever choose just one? No, we need a key that can open every lock. A key that resembles a lock, a letter that is only a word, a glyph like the name of a god: powerful and unpronounceable. Say it anyway, as close as our language can come: and. Look at all the possibilities that lie behind that door.

Mairead Small Staid is the author of The Traces: An Essay (Deep Vellum, 2022).

Read Full Biography