A Keyboard Mind: Hollis Frampton’s Gloria! as Lyric Poem

The Editors’ Blog occasionally features online exclusives by Poetry’s contributors. This installment comes from Alice Lyons, whose poem “Happy Valley” appeared in our February 2015 issue. Past exclusives can be found here.

I was three when I started reading. My grandmother taught me to read with a typewriter. It was easy and quick. The first two words I learned to recognize and to type on the typewriter myself were Cheese Ritz.

—Hollis Frampton

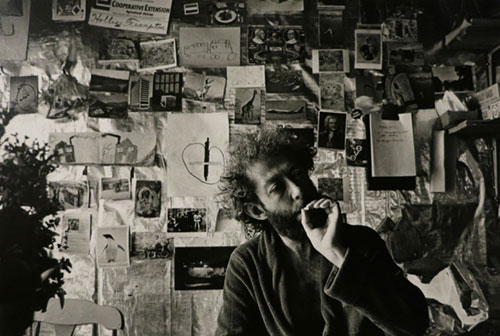

Hollis Frampton (1936-1984) was a meteoric creative intelligence that blew through the arts of the mid-twentieth century. With an IQ of 187 measured when he was ten, Frampton went on to pack a prodigious amount of creative thinking, synthesizing, and making into his short life; he died at the age of forty-eight—meteor that he was, he smoked profusely. He was an accomplished photographer, filmmaker, theorist of cinema, film lab technician, computer coder, and legendary lecturer, member of both the downtown avant-garde art scene of 1960s Manhattan and the visionary Digital Arts Lab at SUNY Buffalo in the 1970s. While he is part of the canon in the world of experimental film, Frampton’s work is essential when considering the integration of poetry and artists’ cinema and video, a field that is burgeoning year by year. Frampton called himself a “non-poet” whose “first interest in images probably had something to do with what clouds of words could rise of out of them.” His films and critical writings—which reach a kind of apogee in the short film Gloria! (1979)—are radical wrestlings with the constituents of language and cinema. Frampton makes the new media future of lyric poetry intelligible.

It is often a footnote in Frampton’s biography that he moved to Washington D.C. in 1957 to be nearer to Ezra Pound and was a frequent visitor to St. Elizabeths Hospital in Congress Heights for more than a year. But Pound’s influence on Frampton was deeply shaping and, in many respects, resonated throughout his whole creative life. Frampton’s attraction to Pound was complex; the brilliant young man from Wooster, Ohio was sorely in need of a mentor and father figure in his early twenties when, after failing to graduate from Phillips Academy, Andover (he refused to sit a required final exam in U.S. History) and therefore forfeiting the offer of a scholarship to Harvard, he was casting around for real direction. He hosted an artsy radio program at Oberlin College, where his girlfriend went, and he read, among other things, a section of the Cantos on air. He soon realized that Pound was at that time incarcerated in St. Elizabeths, and he wrote to him. Pound “shot back like a rocket.” They began a correspondence, and within a few months, Frampton upped stakes and moved to Washington.

I had never intended to go beard Ezra Pound in his den, but the correspondence ripened and it was, in any case, about time I moved to Washington for a period of about a year and a half.... It was for him a particularly interesting time because he was, as I first began to correspond with him, finishing a large block of the Cantos, the part called “Section Rock Drill.” There were a number of other visitors there who were interested in the work and Pound undertook for the benefit of several of them ... an extraordinary thing. That was that he read aloud—this took months—the entirety of the Cantos and annotated them as he went.

While he may not have seen himself as a poet of the sort that Pound was, there were a number of “fearful symmetries” (as Frampton termed them) between the two men. Both were linguistic prodigies who claimed roots in the American “outback,” came East to be educated and were snobs about European high “kulchur.” Both were dab hands on the typewriter; in fact, Frampton learned to read and write on one. Both had radio shows that got them into trouble. Frampton recounted how he got kicked off his Oberlin show: he read on air the lines, “Girls talked there of fucking/beasts talked there of eating/Fucked girls and fat lepers” (Canto XXXIX), and the president of Oberlin heard it. “[At] first, it seemed that I was to be summarily ejected from Oberlin College. Then they found out that I didn’t go there! And I was banished and my excursion into mass communication ended abruptly.” Ezra Pound’s excursions into fascism and anti-Semitism via radio were decidedly more sinister, which is how he came to be detained and awaiting trial for treason.

After a year of discipleship in the “Ezuversity”—Pound later mentioned that he was fond of the young man for “his wit and his dedication to his art”—Frampton abruptly left in March 1958. Apparently they had a violent argument over the color of Aphrodite’s hair, which in one account, is the reason for the break:

We were agreed that it was red. But we got into a color—into an argument about the shade.... I accused him—I think this is what precipitated the rage—of having no real vision of his own but of settling for Botticelli ... and I think I used the adjective “vulgar”—vulgar Botticelli porn, at which point, needless to say, we came to a visionary falling out on the most crucial of matters.

Frampton moved to New York City, turned away from poetry and picked up a camera, beginning an iconoclastic career in photography and film and relegating his relationship with Pound to the past. Poet and friend Barry Goldensohn recalls a cranky and disaffected Frampton in New York in the days around Pound’s release from incarceration and his highly publicized return to Italy. Yet in turning away from poetry, Frampton could not relinquish that early contact with Pound’s “exposition of the poetic process.” His last completed film, Gloria! (1979), finds Frampton squarely in Poundian territory, handling issues of voice, locution, and jostling vocal registers with deftness and originality.

•

Frampton’s wit, as Pound mentioned, and his idiosyncratic style of speech were memorable, even legendary. Filmmaker and friend Michael Snow says that he was the “most extraordinary conversational and public speaker I have ever known ... when he was at his unforgettable best, [he was] a phenomenon of oral, intellectual and emotional energy.” Frampton spoke in lengthy complex sentences, used big words and high diction; he could sound pompous and didactic, and no doubt he could be both. But there is also an element of keen self-parody in what film scholar Bruce Jenkins called the “Oxbridge don” aspect to Frampton’s spoken comportment. Entertaining as it was, this wit and extreme verbal brio were also an expressive power that Frampton managed to lasso and repurpose to great lyrical effect and affect in Gloria!.

Gloria! serves as a dedication to Magellan, Frampton’s thirty-six-hour, utopian, unfinished film cycle that occupied the last ten years of his life. Gloria! is a mere ten minutes of film that manages to be all at once a précis on the history of cinema; a celebration of Irishness, literary modernism, and Kelly green; a treatise on alienation and becoming human through the acquisition of language; a loving homage to Frampton’s robust, bawdy Venus Genetrix of a grandmother; and a lyric poem. Frampton was fond of T.S. Eliot’s observation that a truly new work of art influences and subverts every other work that has preceded in its tradition. In 1975, Frampton wrote, “Indeed, at its most fecund, a drastically innovative work typically calls into question the very boundaries of that matrix, and forces us to revise the inventories of culture ... to find out again, for every single work of art, the manner in which it is intelligible.” Gloria! is such a drastically innovative work. In its remarkable adaptation of the cathode ray computer screen for cinematic effect, and in its deft decoupling of sound and image, the film subverts the constituent elements of cinema to the service of language and forces a revision of both the conventions of the cinematic and the poetic. It jostles the distinctions among reading, writing, listening, and speaking, redraws their boundaries and opens up spaces for cinematic language to behave in the way that lyric poetry can behave. Gloria! offers us clues as to how the lyric poem might have a life in the new media future.

•

Gloria! opens and closes with short black-and white vaudevillian clips from early cinema enacting the Ballad of Tim Finnegan, in which the Irish corpse disturbs his own wake by not being dead: Tim sits up, downs a flagon of beer and dances. These dramatic clips serve as Joycean bookends to Gloria!’s central section, which mimics the world of the digital screen, which in Frampton’s time was a cathode ray tube. After the film opens with a nineteen-second clip called “A Wake in ‘Hell’s Kitchen’” (1903), a hard cut is taken from the black and white world of cinematic illusion and deep space, to the flat, graphic Kelly green space of a computer screen. Suddenly, white alphabetic characters are typed to narrate these sixteen noun clauses about Frampton’s grandmother:

These propositions are offered numerically, in the order in which they presented themselves to me; and also alphabetically, according to the present state of my belief.

1. That we belonged to the same kinship group, sharing a tie of blood. [A]

2. That others belonged to the same kinship group, and partook of that tie. [Y]

3. That she kept pigs in the house, but never more than one at a time. Each such pig wore a green baize tinker's cap. [A]

4. That she convinced me, gradually, that the first person singular pronoun was, after all, grammatically feasible. [E]

5. That she was obese. [C]

6. That she taught me to read. [A]

7. That she read to me, when I was three years old, and for purposes of her own, William Shakespeare's “The Tempest”. She admonished me for liking Caliban best. [B]

8. That she gave me her teeth, when she had them pulled, to play with. [A]

9. That she was nine times brought to bed with child, and for the last time in her fifty-fifth year, bearing on that occasion stillborn twin sons. No male child was born alive, but four daughters survive. [B]

10. That my mother, her eldest daughter, was born in her sixteenth year. [D]

11. That she was married on Christmas Day, 1909, a few weeks after her thirteenth birthday. [A]

12. That her connoisseurship of the erotic in the vegetable world was unerring. [A]

13. That she was a native of Tyler County, West Virginia, who never knew the exact year of her own birth till she was past sixty. [A]

14. That I deliberately perpetuate her speech, but have only fragmentary recollection of her pronunciation. [H]

15. That she remembered, to the last, a tune played at her wedding party by two young Irish coalminers who had brought guitar and pipes. She said it sounded like quacking ducks; she thought it was called “Lady Bonaparte”. [A]

16. That her last request was for a bushel basket full of empty quart measures. [C]This work, in its entirety, is given in loving memory of Fanny Elizabeth Catlett Cross, my maternal grandmother, who was born on November 6, 1896, and who died on November 24, 1973.

This woman whom Frampton termed his “Irish grandma with the style of a drunken sailor” asserts an indelible, physical presence in Gloria!. Indeed, it is Fanny Catlett Cross’s robust inherence in language, her role as giver of language, and the unconventional methods she employed in enabling young Hollis to learn reading and writing that resonate loudest and longest in the film. Contained within Frampton's stated wish in Gloria!’s fourteenth proposition to “deliberately perpetuate her speech,” is the kernel of a notion about lyric poetry as an enactment in language that retains a sense of the alien as much as the intimate. Mutlu Konuk Blasing says that lyric poetry “remembers the history of the process of its own coming into being” and this memory includes our experience of being outside language as aliens before we are initiated into it. Nestled within that kernel of a notion is yet another notion: that Frampton’s Gloria!, in enacting in filmic language its own coming into being, is not a “poetic film” or even a “poetry film” or “film poem.” It is a lyric poem.

•

“Our writing tools are also working on our thoughts.” Media theorist Friedrich Kittler refrains these words from Friedrich Nietzsche, who wrote on a monstrous model of early typewriter in the vague shape of a hedgehog. Gloria! is a work fundamentally shaped by a keyboard mind. As if the spirit of Eadweard Muybridge ghosted his grandmother’s typewriter where the young Hollis perched, the writing tool began tessellating his thoughts. Typewritten letters of the alphabet morphed into images proceeding at twenty-four frames per second. Onionskin paper became, in the future filmmaker’s work, the white rectangle of a cinema screen. The grown-up Hollis Frampton spent the rest of his too-brief, creative life thinking about “Film in the House of the Word,” as he titled one essay. Gloria!, his final act, returns Frampton to his grounding in both lyric poetry and QWERTY.

By using a digital text editor to direct the diction of the propositions about his grandmother, Frampton incorporates both motion and time—cinema’s constituents—into language, not only in the visual formation of the onscreen text but in its meanings and resonances as well. The experience of reading the propositions on the static page is profoundly different to encountering the text in the action of Gloria!. The letter-by-letter progression of the propositions about Frampton’s granny reassert the baby steps the author took in becoming a member of the family of language through recognizing and typing C-H-E-E-S-E R-I-T-Z. Their jerky progression affirms, however flickeringly, the author’s first person singular status. It also embodies the micro-history of his own acquisition of language, which was on a typewriter with his grandmother’s instruction. Gloria! deliberately aims to refract itself through the verbal milieu of both Fanny Cattlett Cross and the filmmaker/poet himself—to perpetuate her speech and his acquisition of a version of it. The animated formation of the text itself becomes an affective force in the film, an element of lyric power. In the process of devising the materialities necessary to communicate this verbal milieu—he writes a code in which to create a digital, onscreen typewriter, his mother tongue, so to speak—Frampton demonstrates how cinematic tools can be freighted with lyric purpose.

Gloria!’s propositions play multiple roles on the “stage” of the screen. The leading edge of the text, as it rapidly comes into being, emphasizes the living quality of its emergence. It animates the figure/ground aspects of language’s coming-into-being. In the process, it destabilizes the boundaries around writing, reading, speaking, and hearing. They appear at first in the diction of writing as they are formed the way text is typed on a keyboard, ghosting the figure of the author whose fingers tap away on the keyboard. We, as cinema spectators of Gloria!’s emerging text, become readers as well. The temporal progression—of type forming words and words forming sentences, appearing in the order in which they would be formed by the tongue and flowing out of the mouth—also conveys an inherent quality of utterance, of speaking. In this sense Gloria!’s text becomes immediately conversational, and we spectators are also listeners. As such, what Garrett Stewart calls the “acoustics of textuality” are conjured; the propositions are burdened with the phonic. This draws into the frame the body of the film’s reader/viewer/listener, “the body as the receptive site of textual activation,” a ground on which the textual and cinematic materialities of the film are inscribed.

The flickering cursor has become, in our time, the site of an individual’s negotiation in the digital world. The cursor provides a foothold in the terrain of the screen from which to be a computer user, from which to be: to move, to act, to speak in digital space. A cursor blinks so that it can be quickly distinguished from the field of static type in which it sits. It is an intermittent, animated figure in a ground of text, something that has become so ubiquitous in the last thirty years as to be rendered invisible. Gloria! does not include a cursor, per se—cursors and Gloria! sharing roughly the same birth dates—but, the animation of Gloria!’s text behaves in a cursor-like way. The cursor is an apt figure through which to delineate the site of “expansion and shift” in the actions performed by language in Gloria!

In its rapid unfolding, Gloria!’s digital text behaves in much the same way as a cursor. Its leading edge, quickly “running” from left to right, becomes a messenger, a figure that mimics the near simultaneous coming-into-being and disappearance of spoken language production. In one instant, the cursor instantiates the action of language, the making of a mark or an utterance; in the next it represents the not-mark, the not-sound of language.

Such movement is a useful figure for pinpointing a nexus of slippage, a site of language making and un-making itself. This tension between the figure of an alphabetic character and the ground on which it is inscribed performs a continuous capturing of what Stewart calls a moment of friction, an “air/ink difference” between “phonemic and graphemic signification.” Stewart proposes the reading of a literary text as “a continual confrontation, within writing, of the phonic and the graphic.” Frampton’s animated text embodies living production of language because it incorporates kinetics into inscription; it becomes a voice as much as it is a written text. It is also a sound as well an image.

•

Frampton often spoke of the 1928 manifesto on sound in cinema issued by the Russian directors Sergei Eisenstein, Vsevolod Pudovkin, and Grigori Alexandrov, which he believed to be mainly if not entirely the thinking of Eisenstein. One of the chief creative problems Frampton grappled with in the Magellan project, which included Gloria!, was the issue of sound. He wrote: “[Eisenstein] offers us an open invitation when he says that the first interesting work that will be done in sound will involve its distinct desynchronization from the image.”

In Gloria! Frampton takes up Eisenstein’s invitation and decouples sound from image. Or more precisely he displaces sound from its referents, whether plastic (as in the early cinema clips) or graphic (as in the digital text of the propositions section). This achieves a number of effects. P. Adams Sitney refers to Frampton’s observation of the supreme power of language over other phenomenon: “[the] language of the computer text in Gloria! exerts ‘power’ over the sound and visual citations so that their denotations dwindle in significance and an expanding connotative range predominates.” The “silent soundtrack” of the propositions section works by asserting silence as it “speaks” on the green screen. The typewritten text liberates the inherent acoustics of the propositions, or as poet Susan Howe has it: “[font] voices summon a reader into visible earshot.” This strobing action of Gloria!’s digital text embodies the | and not | of the cursor, the I and not-I of the lyric poem. In its appearing-disappearing it affirms the figure|ground of the human both immersed in and estranged from the larger field of communal language.

To write/speak/read in this flickering space is to draw the figure of perpetual speech, a kinetics of slippage, of the fleet incisions in the larger fabric of communal language that lyric poetry embodies. Frampton exploits the cinematic medium to make an incision in the act of reading—tinkering with its “Newtonian mechanics” (Frampton) and freeing up its “acoustics of textuality,” (Stewart) allowing the lyric to slip into work. What is churning beneath the propositions put forth in Gloria!? What utterances is it perpetually speaking?

•

Mutlu Konuk Blasing asks if “a human [is] a rational creature, a given prior to or outside of language, who ought to be in control of language? Is a ‘human’ one who forgets the inhumanity of the code in which he or she became a ‘human’?” One effort towards an answer is Hollis Frampton’s proposition: “4. That she convinced me, gradually, that the first person singular pronoun was, after all, grammatically feasible. [E].” He implies a state of being outside of language and outside of an individuated, or “human,” state—a state of being as an undifferentiated and ungrammatical entity. The young Frampton identified most with Caliban in The Tempest, “A freckled whelp hag-born—not honor’d with/A human shape.” In the course of Fanny’s tutelage, he moves gradually from a state of non-I, from gormlessness—ground—to figure, the “first person singular pronoun”: to being “feasible.”

Of course, that particular pronoun is the site of contention in critiques of the lyric mode as the inward-looking, enclosed, solipsistic, “single speaking voice privileging private over public experience, individual autonomy over civic responsibility and aesthetic independence over social engagement, ... a metonym or synechdoche [sic] for the bourgeois subject in all its illusory, self-sufficient glory” as Clare Cavanagh puts it. Yet what is figured in Gloria! in its connotations and the material transportation of its text is an estrangement from the figure of “I” as much as an inhabiting of it. Language is made strange in its digital emergence on the green screen. Again, Blasing elucidates this: “While the sorrows of an ‘individual’ may be a historically-specific resonance of the lyric subject’s discourse of alienation, the alienation in poetic language is not specific to lyrics of bourgeois subjectivity: it is the enabling condition of subjectivity in language.”

Gloria!’s digital typewriter is turned into a machine that enables language of both the lyric stranger and the lyric I to speak. Elizabeth Bishop’s parallel recollection in her poem “In the Waiting Room” is striking in the similar way in which it recalls a phase of childhood in which one is both in and outside a “self”: “But I felt: you are an I / you are an Elizabeth ... I knew that nothing stranger / had ever happened, that nothing / stranger could ever happen.” She articulates a consciousness that is broader than a particular “I” can confine. Both Frampton and Bishop here speak of a nascent recollection of a state of existence outside the “primal frame” (Blasing) of language. Both, too, articulate the strangeness of such an awareness. Lyric poetry is the verbal act that is able to encompass both the inside and outside location of a person in language.

In addition to mobilizing the alienation inherent in language acquisition, Gloria! also captures the subtle qualities of voice that were idiosyncratic and memorable to Frampton’s particular linguistic brio. The desynchronization of his actual speaking voice from the unfolding text that conveys his voice serves to more powerfully amplify it. This decoupling frees the voice from the inertia, in Eisenstein’s terms, from its enclosure in text. On the page, the propositions are frozen, inert and do not have this resonance of living speech. They lack the nuances of meaning offered in onscreen animation. The time-based element allows the text to “act.” The pacing of the text's delivery—sometimes fluent and fast, other times pausing as if to deliberate—fits perfectly SUNY Buffalo’s Center for Media Study founder Gerald O’Grady’s recollection of Frampton’s “deliberately slow, resonant delivery … his thought process, being developed and edited as he vocalized it.”

Hyper-rationality was part of Frampton’s mind, but it was also his shtick. He valued above all else “the ancient art of wit,” and Gloria! is also both a loving homage to Joycean wit and a disavowal of the empirical to the exclusion of all else. Consider the progression from the first two, just-the-facts-ma’am propositions with their diction of rational inquiry festooned with the regalia of ordering systems with the numbers, brackets and letters. “1. That we belonged to the same kinship group, sharing a tie of blood. [A]” and “2. That others belonged to the same kinship group, and partook of that tie. [Y].” The third one, then, acts as a punchline: “3. That she kept pigs in the house but never more than one at a time. Each such pig wore a green baize tinker’s cap. [A].” The language transports a load that is more than referential, even though, ironically, it uses the diction of instrumentality to convey its passions. While the diction of the propositions is skewed toward the scientific, Frampton's careful modulations in the ordering of sentences of factual statement, poignant recollection, delectable idiosyncrasy, and honest self-reflection flow the way a brilliant stand-up routine flows.

Gloria!’s fourteenth proposition offers a way of speaking about what lyric poetry does and can do. To deliberately perpetuate [her] speech is to willfully prolong spoken language, drawing from its past and projecting it to the future. It conjures a corpus of language, a considerable, weighty entity, an immersive medium and a communal one. “Perpetual speech” incorporates both the giver of language and the speaker/writer, the perpetuator. To deliberately perpetuate implies that to do otherwise is to let speech disappear, to die. Action, volition, deliberation: such is the energy required for the art of retrieval, which is lyric practice.

And what is being retrieved through perpetual speech? As Mutlu Konuk Blasing has it, “Poetry is a way of remembering or retrieving the emotional or erotic materials of language on the verge of their disappearance–or rather as the wake or trace of their disappearance, in referential, ‘adult’ language.” Gloria! enacts the practice of lyric poetry, not as a family album of “memories” but as a work focused on the resonances, the locutions, the “emotional or erotic materials of language” of both Frampton and his grandmother and their perpetuation both in the materialities of cinema and within language itself.

Confusion over “rationality,” comedy over tragedy, indeed eternal life (and debauchery) over death—these are the “underwritings” of Gloria! and Hollis Frampton’s mature “overruling” of the high modernism of Ezra Pound in which he was baptized and in which all his work up to this point had been rinsed. Gloria! is the work in which Frampton's absorption of Pound—of locution, multivocality, montage, modernism—and disavowal of him—of the “frowning master,” of the lack of a historical sense, of political obsessions not consonant with his own—is complete.

Frampton is our first significant digital poet and Gloria! is our first digital poem. His eccentric acquisition of language led him to devise a digital “means [of] intimacy and flexibility” so that his lyric voice could ring out with tones resonant enough to reach back through the years to his earliest contact with language. In creating this mode of transportation for his voice—a mode sturdy enough to carry the emotional “freight” of its language and shifty enough to be both alien and familiar—Frampton yokes the bardic past to its fiber-optic future, resurrecting Tim Finnegan and the lyric poem in one go.

Alice Lyons is currently a Radcliffe Fellow in Poetry at Harvard University where she is making, with the help of some Harvard undergraduate research partners from the film and animation department, a film based on Frampton and Pound's typewritten correspondence.

Alice Lyons was born in Paterson, New Jersey and grew up in its suburbs. She has earned degrees in European...

Read Full Biography