Ol’ Bob Dylan Just Keeps Comin’ Back

The Editors’ Blog occasionally features online exclusives by Poetry’s contributors. This installment comes from Kathryn Starbuck, who most recently appeared in our June 2015 issue with the poem “Sylvia En Route to Kythera.” Past exclusives can be found here.

It meant the world to my late husband, the poet George Starbuck, when Bob Dylan wrote him a fan letter in 1980 about one of his books. I’ll amble my way to that letter later. My own tiny Dylan diversion came when he showed up at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, as I was biding my time on campus, counting long days until I’d be able to vacate the place, longing to be where I’d learn something worthwhile, pretty sure I was not going to find it in an alien, insular on-campus world, a place swollen with books and classrooms where I felt incapable of learning, unlike the real world where I felt whole and confident.

I’d completed my first Antioch work-study position. It confirmed my belief that learning on the job suited me. Now I’d won an even more coveted work-study position. When I completed it, I intended to drop out of college, continue to fill and fulfill my life with work and more work until I saved myself and the world with my powers of passion and compassion.

As I sat waiting for my final day in Yellow Springs, some kid on a motorcycle with a guitar on his back was yelling from the curb outside our two-story residence house. I could almost hear what he was saying as I peeped through the open window where my bras hung to dry, just blowin’ in the wind. Was he, by chance, commenting?

“What?”

“Anybody wanna go for a ride?”

“Where to?”

“Around town. C’mon. We could sing.”

“I’ll ask my roommates.”

My three roommates went back to their books. Well, I’d never ridden on a motorcycle. I loved to sing. Since I did not attend classes, no homework awaited; I was extremely busy killing time until the one thing that excited me, when I would become—get this—a White House Dictationist at the Associated Press in Washington where top-notch reporters would rapidly dictate their stories to me. (I’d tested out as a faster and more accurate typist than anyone at Antioch.) The reporters’ dispatches would be edited and sent via AP wire around the world. I’d meet those reporters and other journalists; I might even turn myself into a journalist one day. I was confident it would be a great job, I’d be a spectacular success. In three months, I’d accumulate life-changing knowledge and opportunities. Of course I would meet President Dwight D. Eisenhower. All that and more eventuated. Fidel Castro himself kissed my hand during my first week on the job when he visited the AP newsroom. That same week I was ushered into an Eisenhower Presidential Press Conference by legendary television journalist Eric Sevareid when I allowed him to share a cab with me.

Back in Yellow Springs, I asked the guitar kid, “Where you from?”

“Hibbing, Minnesota. You’ve never heard of it.”

“Sure I have. I’m from Iowa. My dad and I fish the Mankato River all the time. We take River Cat. Be down in a minute.”

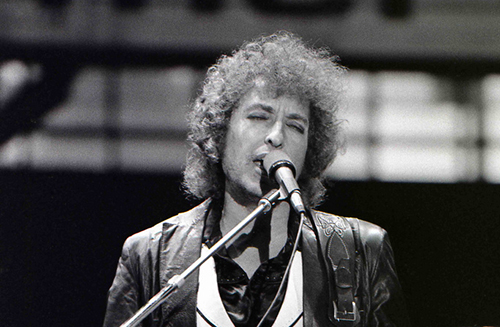

Bob Dylan and I rode around the village on his motorcycle for a while. Perhaps he was calling himself Bob Dylan by then. Can’t remember. During the weeks I tried on college—only to learn that it did not fit—I witnessed stupendous performances by folk artists Pete Seeger, Odetta, and The Weavers. Perhaps Dylan wanted to listen to Seeger or at least see him do the limbo. Or perhaps he was taking a super-long detour from Duluth, Minnesota, where he was born in 1941 or Hibbing where he’d gone to high school. He was a couple of years younger than me. During the hour or so we spent together, he parked his bike, we sat on the grass as he sang to me and played a couple of tunes. I told him he sounded a bit like Gene Autry. I sang some Autry back to him, using my best nasal voice. He said he’d always liked Gene Autry; said I’d given “a big and great” compliment.

It was sprinkling when he drove me back. It’s unlikely that accepting a motorcycle ride with Dylan had any deep impact on my strange young life when the two of us were teenagers in the waning days of the fifties. Soon I forgot about the kid with guitar—although I did record a few lines about the event in my faded Antioch notebook which I’m studying as I write today. My life singing the songs of Gene Autry and Roy Rogers and watching their movies stretches back to a childhood in Algona, Iowa, in the forties. Their songs stayed in my head, and drifted around with me to the places I’ve lived, here and abroad, and called home.

Yellow Springs was the first of four times I saw or thought much about Dylan until October 13, 2016, when he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

*

On August 28, 1963, the second time I saw Bob Dylan, he was performing with Joan Baez in Washington, DC, at “The March on Washington to Support Jobs and Freedom.” The march drew more than 250,000 people from across the nation and the world into Washington. The two were on a crowded stage, entertaining the multitude on an extremely hot day as everyone waited for Martin Luther King Jr.—the stage where he delivered his “I Have a Dream Speech” and uttered some of the most memorable words of his brief life.

That summer, I worked as a volunteer in the headquarters office of Washington CORE (Congress of Racial Equality). Visiting civil rights leaders with various agendas gathered at the shabby CORE headquarters and turned it into a hotbed of activity as August 28 drew near. As the only “girl” and only white person at the office, I was sometimes included during strategy sessions for decoration, to take notes, to type press releases. Shortly before the big day arrived, Andrew Young, one of the national leaders, along with national CORE director James Farmer, came to the office. They required a driver to take them to appointments around Washington. The black leaders made it clear they wanted me as their driver. Even though I vigorously protested, saying I was a dangerous driver with no sense of direction, I was deputized.

The guys liked giving directions. At our first stop, Julian Bond, cofounder of the SNCC (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee) got in the back seat. Next, Martin Luther King Jr. himself settled into the front seat, beside me. Dr. King shook my hand and gave directions to our next stop. “Where did you say we turn, Dr. King?” Off we went for a number of meetings with various big shots stepping in and out of the car, including the brains of the movement, Bayard Rustin. A couple of meetings were actually held inside the car:

—Would as many as 10,000 people show up?

—Would President John Kennedy ever start cooperating and stop worrying about violence?

—Would they (the leaders) never stop bickering and unite on this point or that?

My awful driving scared my illustrious passengers when it did not make them laugh. A few times I was asked to pull over and park for a few minutes while they talked and strategized, argued, worried, and, at one point, prayed for guidance and success.

There was no violence.

Of course I was transfixed by Dr. King as he spoke that day. I was filled with joy and hope as I saw the men I had worked with that summer sitting on stage with him, cheering him on. It was clear to me that the march and his speech were a turning point in history and that King had become the moral leader of the nation. When I listened to Baez and Dylan sing, I momentarily thought back to Yellow Springs and Dylan. It felt like a lifetime ago.

*

The luminous poet George Starbuck and I met in 1964 when he came to teach at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, where I had earlier begun working for Paul Engle, its director. In 1966, I moved on to Chicago. Engle retired. George agreed to take over as director for three years. George and I married in Chicago in 1968. In 1970, George became head of Boston University’s Writing Program. We bought a house in Milford, New Hampshire. I became a political journalist then editor of the country’s oldest weekly newspaper.

In 1980, George’s Talkin’ B.A. Blues; the Life and a Couple of Deaths of Ed Teashack; or How I Discovered B. U., Met God and Became an International Figure; a rhyming fiction, published by Pym-Randall Press, was released. The book, written mostly in the voice of rhinestone cowboy Ed Teashack, is thirty-five pages of rhyming comedic fiction. It is one of George’s idiosyncratic masterpieces.

It was also in 1980 when I next saw Bob Dylan. He was performing in a coffee house in Cambridge, once again with Joan Baez. Maybe Dylan dropped into the Grolier Poetry Book Shop on Plympton Street, near Harvard Square steps from the coffeehouse where he performed, and picked up a copy of Talkin’ B.A. Blues. Or he could have found it at numerous Cambridge book stores. Or perhaps someone gave Dylan a copy.

Not long after seeing Dylan at the Cambridge coffeehouse, George came home with an unopened letter addressed to: Poet George Starbuck, Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts. Return address simply: BOB DYLAN, using all capital letters as I recollect. George asked me to open it, to read it to him. In the more than three decades I worked with, came to love, then married this modest and brilliant man, I saw him blush but twice. George’s left hand, already shaky and compromised by the Parkinson’s disease that caused his death in 1996, after a twenty-two-year struggle, shook ever faster that day. As I slowly read Dylan’s letter, I witnessed his second blush.

Dylan wrote: “Dear great poem-maker Starbuck.” He wrote that he fell at once for Ed Teashack and his struggles at Boston U. George grew beyond happy.

From Dylan’s earliest days on the scene, George had recognized him as a poet of astonishment whose lyrics displayed a unique seriousness, anger, and wit. That letter may have meant more to him than any of his prizes, awards, and fellowships.

It would gratify me to hear from anyone to whom George Starbuck mentioned his prized Dylan letter since I do not know that he mentioned it to anyone but our late, dear friend, the novelist Richard Yates, author of Revolutionary Road, among other works. (Dick Yates and I became friends in Iowa City in the mid-sixties. Our friendship continued in Boston, and here in Tuscaloosa, where he listed George and me as next of kin on multiple hospital admission forms until we made more suitable arrangements for him. Dick Yates died in Alabama in 1992.) George shyly handed Yates his letter from Dylan when we three had dinner at Dick’s favorite restaurant in downtown Boston. “Jesus Christ George, pretty damn great letter,” Dick said.

Of course George lost his prized letter. My late beloved lost things. Or simply gave them away: Books. Cash. The first of his “Space Opera” manuscripts. In Iowa, he gave his typewriter to a student en route to jail for refusing to register for the draft during the Vietnam War. He lost his poem drafts. Letters from….

As I clawed through my cache of eighties reporter’s notebooks, while seeking material for this essay, I ran across this note I’d surrounded in quotes from George: “Kathy, when you become the novelist, the fine writer of modern Greek history, whatever kind of writer that I know you already are, but you have yet to decide to become, you have to write about riding on the back of Bob Dylan’s motorcycle plus how you dug the underground railroad in Yellow Springs.” Stunning how much I’d forgotten. How grateful I am to have hung on to so many notebooks in which I’ve recorded a lot of my life since leaving home as a teenager. I’ll save the story of how I dug the underground railroad for another time. Dylan’s lost letter, as I remember it, was a one-page, hand-scrawled witty number. If memory serves, he signed it, Your fan, Bob Dylan.

*

Here are a few lines from the first chapter and the final page of George Starbuck’s rhyming fiction about Ed Teashack, hero of Talkin’ B.A. Blues, that may have captured Dylan:

THIS IS THE PLACE ALL RIGHT

More one-arm chairs. More pi-r-squares to

stare at. Ain’t it awful.

The same old chalk-eraser rack.

It oughta be unlawful.Playin’ pretend in some upended

glass-and-concrete waffle.A whole new triumph-of-the-mind.

Another edifice designed

To look like someone’s scoresheet full of

boxes-for-the-answer.A few lights broke. A few NO SMOKING

signs in case of cancer.[one page later]

. . . But maybe I

should introduce myself.I’m the Universal Educational

Veteran and Victim.[from the final page]

He’s fake he’s lazy he drives you crazy

he shows up every year

With a dead guitar an’ a bridge too far

bit into by the strings

An’ some stuff he wrote himself, unquote,

somewhere, among his things,

An’ a kind o’ Cisco Houston look,

at least until he sings.

*

By 2016, thirty-six years had evaporated since Dylan wrote his 1980 letter. George had been dead twenty years. Years after his death, I became a poet at age sixty. On the morning of my birthday, October 13, I awoke to news that Dylan had won the 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature. Wowsie. That afternoon, I was scheduled to deliver the medical school’s Art of Medicine lecture/poetry reading, focusing on my poems about grief, suffering, and death. Thinking about Dylan’s exhilarating Nobel news was messing up the somber tone I sought for my presentation.

Today in Tuscaloosa, I sit in my top-floor apartment on the University of Alabama’s campus, looking forward, looking out toward the Crimson Tide’s Bryant Denny football stadium, daydreaming and wondering every now and then about Bob Dylan: will he wheel up on his motorcycle yet again beneath my window? Wouldn’t surprise me. After all, the guy has been showing up in my life for more than half a century.

Journalist, essayist, and newspaper editor, Kathryn Starbuck started writing poems in her 60s. She is...

Read Full Biography