A Handful of Chisels: On Stones & Poetry by Claire Potter

Each month we feature a guest post from a contributor to Poetry’s current issue. Claire Potter’s poem “The Art of Sideways” appears in the May 2016 issue. Previous posts in this series can be found on the Editors’ Blog.

In August 1913, Freud took a summer walk through the Dolomites with two friends, one of them being perhaps Rilke. In the idyll, Freud and the poet discuss how flowers and nature are prone to destruction and decay and possess an ill-fated beauty. And yet, in contrast to the poet’s pessimistic view, Freud sees value, and therefore a heightened beauty, in transience, arguing that scarcity and limitation only augment worth. He explains that what spoils an enjoyment of transient beauty was an antipathy to mourning.

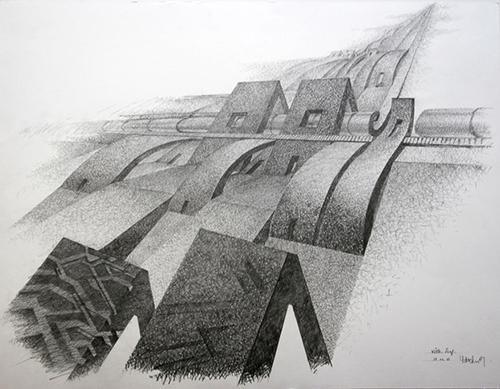

The question of transience—as an expression of mourning—is almost a silent one, residing perhaps between the lines of all great poems—it is the question that stretches, enquires about, what we hold onto in a poem, what remains once the page has been closed. In some ways, it is the infans of the child before they learn how to speak, building word upon word, like raising stones upon a fledgling tower. A tower built, in Mallarmé’s terms, from words not ideas. Often these stones are not squared, their sides are not equal and their angles not perpendicular, leading perhaps to a sentence that wobbles, a wall that inclines, an architrave that bends. And here, residing within, is Freud’s sense of an oblique mourning, a transience we cherish and hold for a fleeting moment, before it is gone, or from another angle, indelibly remains.

Transience could belong to any number of things, and mourning to any number of objects. But they both hold a way of seeing (and feeling) that lies askance to the regular—a regular voice that urges stones required to build a wall be straight, that transience is of lesser value than permanence, and that words, to be understood, follow a communicative order. We are led to wonder why Freud rather than the poet was able to commemorate transience so wistfully: is not the writing of every poem, as Sonnet 18 crystallizes most perfectly for us, an eternal ode—eternal lines to time—to transience itself?

Ruskin was worried about the same kind of questions, wondering if the Stones of Venice were not going to disappear under a pile of seawater and rubble unless he rebuilt them to some extent in his essay. He writes of Poetry and Architecture being the two strong conquerors of forgetfulness, against which fast-gaining waves … beat like passing bells. From this watery grave, at once unbalanced and truthful, Ruskin observes that when we gaze upon a surface of water, we see either one of two things: duckweed (surface) or sky (depth). Due to the physiology of the eye, it is not possible to see both: looking at a reflection of the sky we forget the surface of duckweed as though it were transparent, and looking at the duckweed, we forget the distance of the sky below and above us. The question poses itself, does poetry or architecture change either of these things?

We push the question out further, like a boat into the Styx, to where poetry possibly rises, casting its hook like a fishing line or reel, and catching transience such that its paradox is not solved or scaled by weight or color, but held and returned to the water, unencumbered. This sense of bewitchment is savored in Gabriela Mistral’s poems of mad passion by “mad women”—Locas mujeres—where the woman-unburdened, La Desasida, has a block of stone and a handful of chisels. Mistral makes stepping stones from words and something swerves in her poem, taking us into a new position. She calls, in "La Abandonada," to

Venga el viento, arda mi casa

mejor que bosque de resinas;

caigan rojos y sesgados

el molino y la torre madrina.

¡Mi noche, apurada del fuego,

mi pobre noche no llegue al día!Let the wind come, let my house burn

better than a forest of resin;

let the mill and the braced tower

topple slantwise and red.

My night, hurried on by fire,

let my poor night not last till day!

–Translations from the Spanish by Randall Couch

In these lines, memory is not cherished. Instead a harvest of ashes is sought and dispersed by the wind—vertical lines topple slantwise and red—night is swallowed by day. From the poem, we perceive one of two (or more) thing—time before the ruin and forecast of ruin—as the poet sees

En cuanto engruesa la noche

y lo erguido se recuesta,

y se endereza lo rendido…When the night thickens

and what is upright reclines,

and what is ruined rises up…

Here the poem’s latitude and longitude are reversed—the upright reclines—what is ruined rises up—and night, like a thick web, holds this disobedience in order such that erosion is valued not for the sake of being otherly, but because it holds beauty.

There is something in Freud’s essay proper on “Mourning and Melancholy” (1917) which inhibits him from forthrightly saying, as he is able to do in his more literary mediation on transience, that mourning achieves a profundity of character. That a field of bluebells or a night flower, lasting only a few weeks or even one night, possesses an immortality which defies the fate of disappearance. Intensely aware of what comes after great loss, Mistral’s poem hurries her night on by fire such that her poor night not last until day!

In the mountain scene that Freud and his friends crossed, there resided the paradox of two elements—transience and permanence—in the poet’s refusal to see their difference and their being one and the same. There is resistance, mourning, Freud writes, that pre-empts decline and suffers before loss has even come about. It is perhaps a form of this resistance that reduces the possibility to see duckweed and sky on the same unstable, watery surface. It is on this unstable, watery surface that we topple slantwise … and what is upright reclines, and the poem imbricates any number of possibilities to us, layering stone upon stone until the edifice topples sideways.

The physical activity of falling slantwise or obliquely itself mirrors, etymologically at least, a way of regarding something from a different angle—we see slant, we look sideways, we incline ourselves towards a way of doing something. We tell the truth, in Emily Dickinson’s words, but we tell it slant, or a certain slant of light gives us truth in a different form.

My poem, “The Art of Sideways,” carries the slant of an eye that I have carried since childhood. It was an eye of a snake that Judith Wright portrayed, a colourless eye that glanced at me off the page, ricocheted menace into my eye which in turn reflected my own feelings of menace,

But nimble my enemy

as water is, or wind.

He has slipped from his death aside

and vanished into my mindHe has vanished whence he came,

my nimble enemy;

and the ants come out to the snake

and drink at his shallow eye.

What was I mourning, I wonder, to have let this eye graft itself so permanently onto mine such that even when the snake in my poem had shed its net-like skin, the shape and angle of its eye remains? Does the permanence of this eye lie in the fact that the majority of lines from Wright’s poem are frayed—decayed—in my mind’s eye and with each year they probably decay even more, such that the snake’s eye, thus, takes an even firmer hold?

The brilliant French architect Claude Parent, who died earlier this year, constructed, drew, lived, and breathed along slanted lines, building his repertoire with Paul Virilio upon the notion vivre à l’oblique, a notion that captures not only the psychical, but a simultaneous physical propensity towards moving differently, that is, holding gravity in account. This movement, that fans from 0–90 degrees, makes up the tilt of a right-angle, but also depicts the upright movement from infancy—infans—to speaking adult. Somewhere within this trajectory lies the page—or the screen—usually set at 45 degrees to the sitting, walking, prostrate body. Like ourselves, a page is opened to stand before us, words are read and lifted from a page, and then felled and put away, closed back into horizontal or vertical form. And the melancholy inherent to an imperfect memory of content when poem or book is closed, is made up for by the aesthetic object, like a stone stacked within memory, as an oblique, lost form requisite for re-entering, rebuilding, and rereading.

Claire Potter is from Western Australia. She has published two chapbooks and a full-length collection...

Read Full Biography