Ljubljana

Who: Primož Čučnik, Ana Pepelnik, Gregor Podlogar, and Tomaž Grom

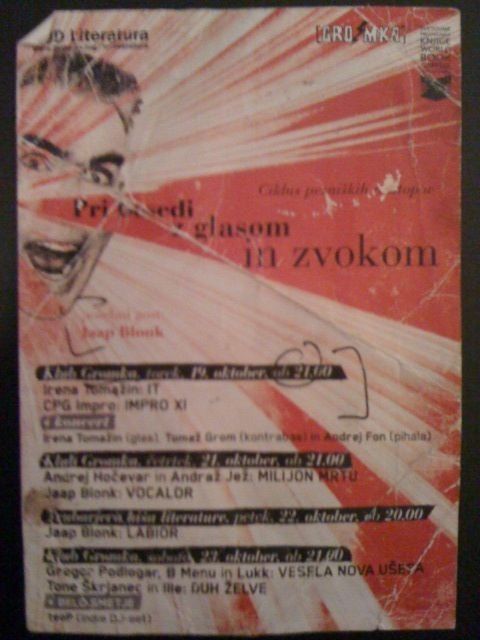

What: "At the Word with Voice and Sound"

When: November, 2010

Where: Klub Gromka: Ljubljana, Slovenia

“Open Door” features audio, video, and online media to document dynamic interactions between poetry and its audience. “Open Door” showcases performance, scholarship, and engagement outside the usual boundaries of slams, workshops, and book publications. This week: the bright and dark in Ljubljana, Slovenia.

***

In the second week of my seven week stay in Ljubljana the literary journal Literatura hosted “At the Word with Voice and Sound”, a weeklong festival of poetry, sound poetry, and poetry and music collaborations at Klub Gromka in the Metelkova zone near the city’s center. It is impossible to imagine contemporary cultural life and nightlife in Ljubljana without Metelkova, the former base of the Yugloslav army in the Slovene capital. After independence it was transformed into a warren of squats and then into the semi-legal club zone that currently hosts most of the city’s alternative music venues and dance clubs, queer and otherwise. Still owned by the state, and positioned on the edge of the city center, it is constantly under threat of being leveled for commercial development, but persists for the time being. It is often mobbed with Slovene youth until well after dawn on weekend nights.

Among the performers on the first night was the music and poetry improvisational group Improv it, made up of Primož Čučnik, Ana Pepelnik and Tomaž Grom. Čučnik and Pepelnik seem two of the more exciting poets of their generation in Slovenia. Čučnik’s work, which is exceedingly difficult to translate, is sparse yet generative, and somehow both very direct and obliquely thoughtful; some of the poems available in translation also deal in a complicated and genuinely moving way with questions of language and identity in contemporary Europe. Pepelnik’s work is characterized by a nuanced and unparaphrasable feeling and tone that she culls from the miniature landscapes she makes of everyday objects and scenes. Some of their work can be read in English online here. Grom is an experimental musician, of tremendous talent and inexhaustible energy who works widely all across Europe and is at the center of the Slovenia’s lively experimental music scene. You can listen to a recording of the performance here.

While Grom improvised on contrabass, plucking, bowing and thumping at its body, and Čučnik played with turntables, sound loops, and improvised noise and rhythm with a vast collection of toys and household objects (which were scattered all across the stage by the end of the performance), Pepelnik—who is a rather slight, almost elfin person with a severe stage presence and deep and affecting reading voice, made improvised selections from a collaged bank of text prepared by Čučnik for the group. The text consists of collaged snippets from John Cage, Gertrude Stein, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and others, much of them having to do with sound and with listening. I found them an enrapturing act. I remained affixed to my seat, washed over by the speech cadences and the tricklings, plings, rattles and crescendos of the sound bath they poured. Other performers that night included Irena Tomažin, a much admired Slovene sound artist and dancer. Tomažin is possessed of an uncanny ability to produce sounds which are difficult to trace back to their source—which is to say that her work with voice exaggerates the already acousmatic nature of the human voice, a phenomena important in the influential work of contemporary Slovene philosopher Mladen Dolar. Tomažin’s were not the only performances in the festival that played with this phenomena.

The very next morning a tiny controversy erupted in the world of Slovene poetry that might help contextualize this festival and the work of the poets around Literatura. Čučnik was at the center of the “scandal.” In the weekly literary supplement to the national daily paper Delo, Čučnik (39), who writes a monthly column, attacked a key group of poets of the post-war generation. At the end of the piece, after likening reading their verses to riding in a car driven by a driver with his foot always on the brakes, he called on this group of so-called “old modernists” to “retire.”

Adjacent to, or perhaps beneath the aesthetic differences the piece pointed to, lay some conflicts over the allocation of resources and prizes. The piece began with a conversation Čučnik was a silent party to, on the streets of Ljubljana, between major Slovene poet and important political dissident from the 80s, Niko Grafenauer—whose dense hermetic work has often been likened by himself and others to Mallarmé’s—and a journalist with whom Čučnik had been talking. Grafenauer invited the journalist to come with him to the committee meeting for the most important Slovene book prize, claiming that he, as the committee’s chair, already knew who the winner would be, despite the fact that final debate and voting had yet to occur. According to Čučnik, Grafenauer then un-self-consciously remarked that it was essentially “his turn.” Certainly we are all familiar with this “lifetime achievement award” type scenario in American Letters, but Čučnik was outraged—clearly also on aesthetic grounds.

The poet Gregor Podlogar—priniciple organizer of “At the Word with Voice and Sound” articulated where he and Čučnik, Pepelnik, Tone Škrjanec, and others associated with Literatura place themselves in relation to Grafenauer, the work of much of Grafenauer’s generation and, by extension, within the body of modern Slovenian poetry. Podlogar, whose poems can be seen as combining the impulses of the Russian and Slovene avant-garde with the intimate poetics of the New York School, is a buoyant and emphatic presence, possessed by a seemingly endless source of energy. Podlogar traces two lineages beginning after the war, one coming out of the work of the great Slovenian avant-garde poet Srecko Kosovel and passing through the work of Edvard Kocbek to the singular work of Tomaž Šalamun and on into the work of his own generation. He calls this lineage “bright modernism” in contrast to “dark modernism,” an accepted short hand term in Slovenia for the work emerging after the war, the darkness coming from the poetry of Dane Zajc and continuing, for Poglogar, in the work of Grafenauer and his peers.

As one would imagine, when I described Podlogar’s binary construction to other Slovene poets and readers there were numerous objections—most on the grounds that it was too simplistic and that Zajc and Šalamun in particular have exerted too wide an influence to divide Slovene poetry into “followers” or inheritors of the “tradition” of either. Even associates of Podlogar at Literatura had their objections; the poet Barbara Pogačnik positioned herself as an admirer of Podlogar’s and Čučnik’s work, and of the work of Grafenauer. She told me she found in reading Čučnik’s and Grafenauer’s work similar pleasures, for the denseness and enigmatic quality of their language—which she is not alone in saying renders the work of both poets essentially “untranslatable.” Podlogar finds no similarities between Čučnik and Grafenauer. He sticks to his lineages, along with his rejection of what he calls “old modernism” or “dark modernism” and what he sees as the 60s generation’s self-importance, its excessive reliance on Heidegger and hermetic language and the use of opaque symbolism and paradox.

The objections of Pogačnik and others notwithstanding, this division Podlogar maps, between the poetics of “dark modernism” and the work of Šalamun, has been articulated by others. The Slovene critic Matevž Koš draws a line explicitly separating the work of Šalamun and his friend Grafenauer. Koš notes the extreme influence of Heidegger in the work of Grafenauer and the poets of his generation—evident in the importance of “silence” in their work. He identifies in the work of Šalamun something almost like the exact opposite. Whereas Grafenauer has spoken of poetry as “walking on the edge of silence”, or as being “condensed silence”, according to Koš, Šalamun’s poetry, with all its bodied noise, conceives of poetry more as “process.” It’s a poetry that never finds itself in the service of an idea or tradition, but is more about “language formation,” in Kos’s conception—something evident in what he calls the famously prolific Šalamun’s “graphomania.” (Šalamun himself in conversation has jokingly claimed to have been writing “language poetry” before the language poets. He has also described the incredible influence of Heidegger on the intellectual life of his generation as evidence of an unhealthy Slovene need “for intellectual fathers.”) Here, it would seem, we are back again at Podlogar’s distinction between dark and bright (or should we say “quiet” and “noisy”) modernisms.

The more I talked with poets about the issues Čučnik brought up with his column and the lineages Podlogar had drawn for me in his explanation of its background, the more I came to see the controversy as indicative of a longer-term more general struggle over the meaning of the legacy of modernism and the avant-garde itself, with serious local historical and political issues inevitably intertwined. At least in this mini-festival, in its very conception, we can see that Literatura, and the group of poets around it clearly were privileging energy, play, noise, laughter, the body and the voice, and a generative, improvisational poetics over a measured, condensed and hermetic Heideggerian engagement with silence and being. Whether that distinction is as stark and as central to Slovene poetry as Podlogar and others maintain, it certainly has its reverberations within that lively world.

Gregor Podlogar reads "Sedmo Pismo."

Anthony McCann reads his and Podlogar's translation of "Sedmo Pismo."

***

Anthony McCann was born and raised in the Hudson Valley. He is the author of I ♥ Your Fate (forthcoming from Wave Books in 2011), Moongarden (Wave Books, 2006), and Father of Noise (Fence Books, 2003). In addition to these two collections, he is one of the authors of Gentle Reader! (2007), a book of erasures of the English Romantics, along with Joshua Beckman and Matthew Rohrer. He has taught English as a Second Language in the former Czechoslovakia, South Korea and Nicaragua, as well as in New York City. Currently he lives in Los Angeles, where he works with Machine Project and teaches in the School of Critical Studies at the California Institute of the Arts.

(If you would like to pitch an “Open Door” feature concept, please email [email protected] with “Open Door” in the subject line.)