Photograffiti in Paris—part 4 of 4

Who: Andrew Zawacki

What: Paris graffiti

When: June, 2012

Where: Paris, France

“Open Door” features audio, video, and online media to document dynamic interactions between poetry and its audience. “Open Door” showcases performance, scholarship, and engagement outside the usual boundaries of slams, workshops, and book publications. This week: Photograffiti in Paris.

***

Things going up and getting torn down: such is the arc and essence—the life cycle—of graffiti, from the Neolithic to neon modernity. Construction followed by demolition, raising and razing in one fell swoop. Graffiti is composition by field, with a wrinkle: the field is composted every night with the latest dicta and chicken scratch. No such thing as a tabula rasa: a law of all writing that graffiti makes explicit, with the old becoming the literal canvas for newness.

On the corner of rue Bachat and rue Faubourg du Temple, a corrugated barrier, barraged with graffiti, frames a large-scale worksite. Curiously, one panel is for, or else signed by, “MÅRX”—halo over the A. Maybe the whole thing is a bilingual, self-referential homophone: marques, marks. Though “interdit au public,” the rubbled courtyard is tagged like a rainbow some kids played piñata with. Splayed in HD chromatics around this would-be no-man’s-land, what amazing, vivid cryptograms can be peeked at by the passerby from certain angles or, thanks to Fossile Urbain Goncourt, through peepholes drilled into the metal. Dramatis personae: SNAK, FAKi, AOC, Rěbus, SVT 187, and JEAK 187, presumably also known as :jEAK_> , the first letter a colon, arrow falling below. How hard it is to differentiate call sign from signal, to discern where Imagism stops and bona fide pictures begin. Nor is it easier to figure out exactly whose name, or whose memo, belongs to whom. To the degree that a wall is rarely spelt by the same tagger twice in a row, graffiti is a multi-player, open-source arena. Despite the competitive frissons of its banter, graffiti gathers a polyphonic, physically dispersed populace, performing a site-specific community through the aesthetic collaboration of who knows how many rotating interlocutors. DIY, but in plural.

The participatory ethos of graffiti is facilitated by its relatively democratic means: a 400ml can of Molotow Premium, for example—no dust / anti-drip / all-season / covers all—, runs a fairly affordable 3.80€. If it ain’t exactly the poor man’s pigment, it’s not a motion picture camera, either, and doesn’t require a grant, a gallery, a family of means. Graffiti is finally a social art, albeit a variety of communication that eschews direct interaction: “community without community,” as Jean-Luc Nancy has figured literary sociality in the wake of Communism—or an adult strain of the so-called “parallel play” endemic to children’s games. In that sense, perhaps our arrant need to forge graffiti is aboriginal, an oblique way of existing beside one another, together but still apart, a roundabout and respectful manner of being “with,” by going without. Regardless of the form or anamorphic temper it takes, writing is the infra-

structure of who we are, articulating our Being Here—an intricate, jangling helix of the human.

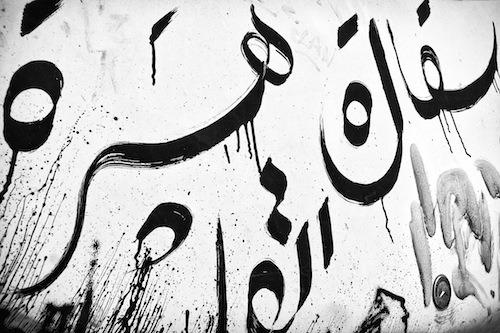

“Graffiti in the sense of ‘write your name and leave a mark on a wall,’” argues type designer Pascal Zoghbi in his co-authored Arabic Graffiti, which I found up the street in Le Genre Urbain, “existed in the Orient long before anyone in the Occident learned what writing was.” A wall or, parked in Belleville, an off-white utilities van (see below). In fact, graffiti from the basalt desert where Jordan, Syria, and Saudi Arabia meet is the only known source of the proto-Arabic language Safaitic, which dates from the first century B.C. and was gone five centuries later. Zoghbi states that today’s “aerosol Arabic” has inherited early techniques of calligraphy, revising and repurposing tradition. If this seems true on the visual level, I suspect a further element, integral to the affiliation: time. Like calligraphy, graffiti traffics in the transient. What might it mean, then, to photograph such writing, when photography likewise “allies itself with calligraphy,” as the late Alix Cleo Roubaud proposed, “through the repetition of an exercise that aims to achieve a flawless instant”? To still one art’s distillation of time, by means of another medium’s millisecond…

At risk of westernizing the writing above, which in any case I cannot read, I thought immediately of the abstract expressionist painter Franz Kline. His beautiful, austere, often black and white calligraphic works are part of my aesthetic blueprint, coursing through my bloodstream like a peloton of grayscale leukocytes, and I can’t help but see his imprint haunting this monochrome Mercedes hood. From 1972 to ’75, Kline became the posthumous occasion for 75 photos of graffiti taken in Peru, Rome, and Mexico by Aaron Siskind. It took the Black Mountain photographer a decade following the death of his friend to begin his Homage to Franz Kline, though he’d been shooting grainy, grungy walls, storefront riffraff, and other vagrant jottings and knotty veneers since the early 50s. After Siskind’s series, photography and graffiti are indelibly linked—if they have not always been. Despite its realism, photography is “shot through with abstraction in its composition and in its rhythm,” according to Roubaud, and so is “close to gestural painting.” Indeed, there are paintings that belong to photography, she said, and photos that do not.

Of the photos I took for this project, I like the one above best. The maximal minimal: it’s nearly not even there—not a seraph of serif in sight. Whisked against a barricade, like a microchip gummed to a mammoth: you could easily miss this molecular collage. Soap, spit, bird shit? Glue from a ripped proclamation? Is that 8 or 80, or infinity? A shard of “luminous debris” (to borrow the late Gustaf Sobin’s phrase), this precarious composition is a seascape relayed by satellite, or a thumbprint a giant left: there’s texture here, slight but wounding, that troubles two dimensions by blossoming into Braille. The erotics of its fragile material life: sensuous or desiccated, graffiti is never flat—I haven’t yet said how badly it begs to be touched. Lake ice, crinoline, bottle glass, bark: skin the chameleon mark comes in. Tinsel, shrapnel, flakes off in your hand, laidline after a flood, burnt croissant. Silk, onyx; sex, flax. Ouzo or 5 o’clock shadow, or straw. Image format RAW.

Graffiti is a sequence of palimpsests, and every graffitist is legion. To tag is to indulge a version of Penelope’s twofold art: unstitching by night, with the left hand, the textile a right hand wove the night before. A feedback loop, antiphonal: there is no sui generis genesis. No innocence or innovation, nothing new-fangled or novel, without erasure, or at least without effacing the past by spraying over the present. Roubaud’s insistence that chemistry makes a photograph a “real trace of the world,” not mere reflection or interpretation, pulls it into further rapport with graffiti. Imagine an archive of graff: impossible idea. Like the photo chez Roubaud, graffiti “is lived like a future perfect: when you see it, this will no longer be.” No inscription without recollection, though remembering be in vain, and every stroke of graffiti, elegy.

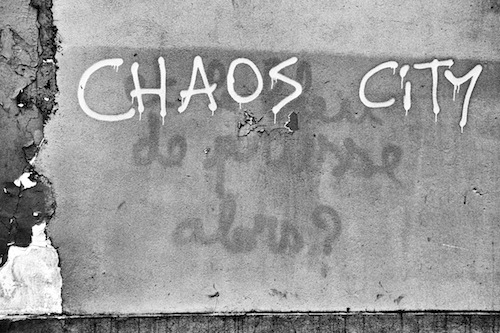

Chaos City: the latter term bespeaks organization, the former the lack thereof. This oxymoron is an efficient characterization of graffiti as an unusual social praxis: people gathered in separateness. Speaking of rifts: I never saw the writing behind the writing in the image below, neither when I shot the shot, nor when I pulled it out to use in a separate part of this blog. It wasn’t until messing around in Photoshop, just to see what the heck, that the question-cum-provocation, “et le bleu de prusse alors?” (and what about that Prussian blue?), became visible. I don’t know what the phrase means, but I presume it’s not primarily a reference to PB27 on the Color Index. I failed to find allusions in French soccer lore or political baiting. Best I can hazard is that offensive, white nationalist pop duo—American pre-teen blond chicks—that toured Europe in 2007. One way or another, “Often what you see is what you get,” as poet Nicolas Pesquès remarked, on a recent &Now Festival panel we shared with Suzanne Doppelt and Julie Carr, “but in what you get,” he added, “there is also what you do not see.” Latent here under the marquee tag, French performs its role as a root of English. Meanwhile, back at the lab, it’s divination by dodge and burn: ironically, photography has excavated, through b/w alchemy, the very blue that graffiti—with its sparkling, spackled color—had interred.

Coinage of the term seems to have understood its relation to ruin in advance: graffiti came into popular use in 1851, to describe the ancient wall inscriptions found among the detritus of Pompeii. In France, of course, we think of the Lascaux cave paintings dating from the Upper Paleolithic, some 17,300 years ago. In Paris Underground, Caroline Archer, a Reader in Typography at the Birmingham Institute of Art & Design, with the help of architect Alexandre Parré and photographer Gilles Tondini, traces five hundred years of subterranean markings in Paris—less the cliché city of light than a tenebrous, mildewed fantasia—memorializing events from the French Revolution to the 1960s student strikes. In the upper world, though, graffiti is seldom around long enough, say a day or two at most, for memory to kick in. Use it to signpost your walking tour—like Hop O’ My Thumb and his mnemonic breadcrumbs, or the Reese’s Pieces trail in E.T.—and you risk staying lost for good. And if you don’t have your camera on you, my regrets: you’d better not plan to just come back tomorrow. You’ll find some other graffiti has swiped its place—if it hasn’t been wiped.

A pack-and-play beach, bivouacked along the Seine for a month each summer, Paris Plages is not this city’s only rapport with sand. Far from the flirtation and tourist frolicking (which opens July 20th), at Mº Stalingrad, I met two guys who clean graffiti for a living. Instead of rattling ball bearings—known in the tagging trade as peas—they blow it off the walls with an air gun, powered by a portable generator, which drives sand through a tube to exfoliate the paint. Gino and George (who kindly granted me permission to photograph him) bust their ass getting rid of rubbish in the 18e, 19e, and 20e , from foyer floors to station doors, publicity posters to piss—no dearth of readymade surfaces to receive the dégueulasse glut. Terrifying in his clinical getup—neurosurgeon or riot police, with a queasy hint of animal snout—this vigilant monsieur, though friendly, is the fuzz: the anti-graffiti. The business isn’t un-messy. When I stepped away from shooting—fifteen minutes later, max, and never closer to George than fifteen feet—my graphite tinted Nikon was khaki: a cellophane of sand. The stuff was everywhere, a sequined Sahara banked against the refurbished brick of the kiosk. Looking down at the salt and pepper flecks, I had the solemn, admittedly sentimental thought that I was staring at atomized art, or the minced pirouettes from a ruffian’s pen, maybe the fag ends of insurrection itself—the jinni of graffiti still in my throat. All literature, Blanchot maintained, moves toward its evaporation: ashes to ashes, dust to dust. Then they swept that up, too.

Dirty / To Be / Washed. I dig the irony: the only thing clean on this pitiful city services truck is the writing inviting someone to clean the truck. Its ambitions might be small and wry, but the itty graffiti is the offspring of an entire à la mode movement. Reverse graffiti supposedly began when Paul Curtis, the British street artist known as Moose, got the idea while washing dishes. Like etching or engraving it’s art by subtraction, making by taking away, but with a green, good Sa(mari)tanic twist: Blake’s infernal method, applied to urban grime. On this day, rain returned the vehicle to its bureaucratic, eggnog hue.

I launched this on-the-fly photo-essay, earlier this month, by averring that graffiti is writing proper to night. But day submits its graffiti, as well, at least as startling as anything done by dark, and more brittle still. The sporadic, serendipitous graffito of shadows and altering shapes, while reliant on the landscapes we engineer, is utterly without author, save the sun. More fickle than its famous cousin, contingent on when and where exactly, on infinitesimal gradations of light, graffiti cast by the sun itself is so evanescent it can scarcely be said to be. Sustainable is the wrong word: bike path or beer cellar hatch, it doesn’t stay in place—it skulks; now and again, dappled or daubed, it peters out altogether. We’ve nearly reached the limits of the genre, at least in formal, mechanical terms, as far as I can see: the vanishing point of this deliberate but unstable art—in medias res from its opening move and destined to disappear—that doubles as an encounter with the ephemeral as such. Nonsensical even to posit that, really: “ephemeral as such.” What can we say about “writing” done by the sun? Carbon footprint zero, it’s more environmentally sound than Andy Goldsworthy’s sculptures and way more eco-conscious than the resins, acrylic lacquers, enamels, adhesives, solvents, and other compounds in the spray paint that—sooner, not later—will prevent the sun from going round, period. But until then, graceful as a Chinese ideogram, or a cigarette wrapper skittish in wind, solar glyphs are to graffiti what the photogram is to a photograph: the world “worlding,” without our help, the surface itself exposed. As sensitive as silver halides—or a 12.3-megapixel DX-format CMOS imaging sensor—, the city is multigrade fiber, and blank, to be writ in invisible ink.

![]()

Almost. Always. Already. Éloigné.

[Note: a brief coda to “Photograffiti in Paris” will appear later this week.]

Andrew Zawacki is the author of three books in France: Carnet Bartleby (2012) and Georgia (2009), both translated by Sika Fakambi and published by Éditions de l’Attente, and Par raison de brisants (Grèges, 2011), translated by Antoine Cazé, which was a finalist for Le Prix Nelly Sachs. Zawacki’s translation of French poet Sébastien Smirou, My Lorenzo, is recently out from Burning Deck.

(If you would like to pitch an “Open Door” feature concept, please e-mail harriet@poetryfoundation.org with “Open Door” in the subject line.)

Andrew Zawacki is the author of five books of poetry: Unsun : f/11 (2019), Videotape (2013), Petals ...

Read Full Biography