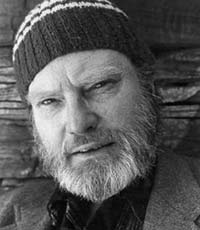

Hayden Carruth (1921-2008)

Last summer, I was asked to write something about Hayden Carruth, and I did, but the folks who had asked me to write the piece never published it. Carruth died in September of last year. He had been an idiosyncratic but pervasive force in American poetry -- both as a writer of poems and a critic of poetry -- for more than fifty years. Here is a link to his obituary in the New York Times. And below is the appreciation I wrote last summer. It's lazy of me, recycling old material here, but I'm grateful to have the opportunity to offer this piece for your consideration. Hopefully it will both garner Carruth some new fans and spark good memories for old ones.

It’s an ancient story: I went to graduate school because I thought I was smart, and immediately discovered how stupid I was. Among the many indicators of my ignorance, one stood out: Hayden Carruth’s Collected Shorter Poems, which had just won the 1992 National Book Critics Circle award for poetry. I went to school at Syracuse, from whose faculty Carruth had only recently retired, and he retained the status of a household god in those parts. He is older now, nearing ninety, and I doubt he does much socializing. But those fifteen years ago, he would be installed in a corner at parties, offered tidbits and drink, doted upon and feared. I tended toward the fear end of the spectrum. I never spoke to him. But I read his poems.

I wish I could go back and watch that kid I was reading those poems and turning pale and clammy as the winter skies of upstate New York. For starters, there were so many of them: two hundred or so, from thirteen books, written over more than forty years. Then the chilling realization that there had to be even more somewhere, since these were only the “shorter” poems. (Copper Canyon published a companion Collected Longer Poems in 1993.) And then there was the extraordinary diversity of the poems themselves. Formally, it seemed Carruth could pull off anything. There were poems in all manner of meters, rhyme schemes, stanza patterns, and received forms, some of which I recognized, others I knew I should know but didn’t, and not a few I suspected had simply been invented by Carruth himself. But Carruth was not a strict formalist, or not exclusively; there were also poems that scattered language across the page, using white space for pacing, and poems in very free verse, some with lines of two or three syllables, some with lines as gigantic and manic as Ginsberg’s, and every imaginable variation in-between. For a young writer who hadn’t (hasn’t) yet figured out how to do even one thing well, this apparition that could do at least a dozen things brilliantly was terrifying.

Beyond the remarkable how of the poems—the solidity and variety of their constructions—there was also the what to be reckoned with. I’d read a poem like “Marshall Washer”--a deeply felt, sternly authoritative account of Carruth’s friendship with his farmer neighbor in rural Vermont, full of insight and information about spreading manure, raising cows, and building fences--and think I had a bead on Carruth’s tone and concerns as a poet. But then some pages later I’d come across translations of short lyrics by Nerval and Lamartine, and be forced to expand my sense of what he was up to. Then there were pitch-perfect and hilarious dramatic monologues in the voices of working-class rural New Englanders trying to keep body and soul together on their dying farms and in their dying mill towns. Then paeans to classical Chinese poets. Caustic political poems about Vietnam, nuclear weapons, and industrial pollution. Erudite lyric flights with titles like “Almanach du Printemps Vivarois” and “Loneliness: An Outburst in Hexasyllables.” Ecstatically ragged analyses and recapitulations of obscure old jazz recordings (“When Dickenson came on in it was all established, / no guessing, and he started with a blur / as usual, smears, brays – Christ / the dirtiest noise imaginable / belches, farts / curses / but it was music . . .” (“Paragraphs”)). Nature poems, love poems, political poems, lyrical poems, narrative poems, dramatic poems, funny poems, serious poems, angry poems, sad poems, joyful poems. The poet seemed at ease with Chinese, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Indian, French, Italian, German, and English literatures. He also knew how to bale hay. He was witty and scholarly, but utterly allergic to bullshit and pretense. Who was this guy? When I came to “A Little Old Funky Homeric Blues for Herm,” and after much study realized what I was looking at—the 2,700-year-old Homeric hymn to Hermes, recast in jazz slang (“Knock off that hincty blowing, you Megarians, / I got a new beat, mellow and melic, like / warm, man. I sing of heisty Herm”)— my last screw came loose. Was such an exercise supremely nerdy? Sure. Was I nevertheless supremely jealous of the poet’s knowledge, and wholly won over by his humor? Absolutely.

The equal measures of anxiety and enjoyment I felt as I came to understand the depth of Carruth’s technical skill and vastness of his frame of reference ensured I would return to his Collected Shorter Poems again and again as I struggled to bring together my own first book of poems. But these years later, taking the book down from the shelf, it’s not so much the how or what that strikes me as the why. When I think about why these poems were written—what it was that hurt Carruth into poetry, to borrow Auden’s phrase—I realize that reading them, I never feel the author is writing to be admired, or to fulfill or defy expectations, or to dazzle or baffle or flatter or decree. Carruth never panders; not to himself, and not to us. Galway Kinnell’s blurb on the back of the book gets it right: “This is not a man who sits down to ‘write a poem’; rather, some burden of understanding and feeling, some need to know, forces his poems into being.” And T. S. Eliot, describing his “Impersonal” theory of poetry in “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” makes the point even more clearly, in terms which seem to me to describe Carruth’s achievement perfectly:

"There are many people who appreciate the expression of sincere emotion in verse, and there is a smaller number of people who can appreciate technical excellence. But very few know when there is expression of significant emotion, emotion which has its life in the poem and not in the history of the poet. The emotion of art is impersonal. And the poet cannot reach this impersonality without surrendering himself wholly to the work to be done. And he is not likely to know what is to be done unless he lives in what is not merely the present, but the present moment of the past, unless he is conscious, not of what is dead, but of what is already living."

It’s hard to learn how to write poems, and it’s hard to decide what to write them about. It’s hardest of all, though, to discover (or create) a good reason to write them at all. I don’t think I realized when I read Carruth’s Collected Shorter Poems in 1992 that the most crucial lesson he had to offer me was the necessity of confronting that fearful task directly and continuously, with honesty and integrity. If I’ve begun to understand that lesson in the years since, it’s in no small part thanks to the present moment of the past which lives in that book’s pages.

-- JULY, 2008

Born in Grand Rapids, Michigan, poet Joel Brouwer earned a BA from Sarah Lawrence College and an MA ...

Read Full Biography