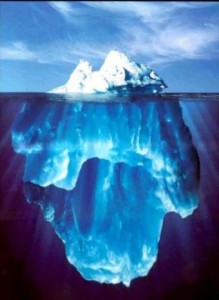

That “why don’t you write novels” question Camille Dungy refers to is one I get all the time. Once, I was reading my poem “Aunt Leah, Aunt Sophie and the Negro Painter” which is about, oh, you know, Black-Jewish relations, Socialism v. Communism, secularized v. religious Jews, Paul Robeson, conservatism, late Cubism, Ariel Sharon, O.J. Simpson, 20th Century history, two pairs of sparring sisters, that sort of thing—and someone said “aha, a novel in verse.” I think you have to rhyme to be able to call your poems verse, the phrase “free verse” notwithstanding. But I was rather flattered. (The person who said it is a famous novelist.) Still, it’s not a novel, it’s certainly a poem. Why? The poem’s not interested in development. It’s about instability and conflict in stasis. Good poems, to me, usually achieve an exciting imbalance. You can get to that state by all kinds of means and poetics. When I write a complicated story poem, I’m trying to get to that point as much as I am when I write something more lyric and less narrative. I want the poem to stand up on its own but appear to be in danger of falling down. Beachy Head before it actually did fall. Ezra Pound said somewhere that poems should be like icebergs. Just the crisis. In my story-poems, the goal is to have only a little bit of the story sticking out of the water, and you know that’s only a tiny fraction of the huge chunk of ice—the rest is there, but out of sight under the water. I don’t think that’s what novels do. In most novels, somebody changes. Or fails to change. There’s development. Events happen, characters respond. In my poems, the novel might be under the surface. But things don’t change. They just stick out there, craggy, asymmetrical. Evidence. But of what?

Daisy Fried is the author of five books of poetry: My Destination (forthcoming 2026); The Year the City...

Read Full Biography