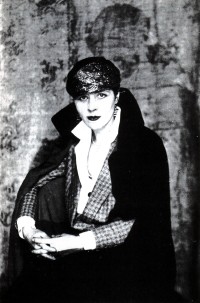

“Cheep like the cricket”: Looking at Djuna Barnes’s Ryder

MAKE Magazine has Len Gutkin reviewing the 2010 Dalkey Archive reprint of Djuna Barnes’s 1928 novel Ryder, the modernist and rather bawdy work that drew heavily on her childhood experiences (and set up the author herself as patriarch Wendell Ryder) and was influenced by the shifting of styles befitting one James Joyce. Ryder was also briefly a New York Times bestseller, but many of its French folk art–inspired illustrations were cut from the original (replaced by Dalkey in the new edition) due to their unrefined nature. (Images removed include one in which character Sophia is seen urinating into a chamberpot and another of daughter-in-law Amelia and son’s mistress Kate-Careless sitting by the fire knitting codpieces. Shouldn't be a problem!) In his review, Gutkin expands on Barnes’s influences, delving into, interestingly, the literary models for the litany:

Barnes was a great devotee of Joyce and surely felt authorized by his example to experiment with the long, litany-like, word-drunk line. In a 1936 article, she writes that she first “sensed the singer” in Joyce reading lines like Ulysses’ “Thither the extremely large wains bring foison of the fields, spherical potatoes and iridescent kale and onions, pearls of the earth, and red, green, yellow, brown, russet, sweet, big bitter ripe pomilated apples and strawberries fit for princes and raspberries from their canes.” Every page of Ryder delights in this joyous Joycean list-making.

In Ryder, such paragraph-, page-, even chapter-long enumerations often involve themes of parentage and generation, those Biblical “begats” ever hovering in the background. Consider, for example, one of Wendell’s many obsessive orations on fatherhood, here given a metaphysical turn:

I, my love, am to be Father of All Things. For this I was created, and to this will I cleave. Now this is the Race that shall be Ryder—those who can sing like the lark, coo like the dove, moo like the cow, buzz like the bee, cheep like the cricket, bark like the dog, mew like the cat, neigh like the stallion, roar like the bull, crow like the cock, bray like the ass, sob like the owl, bleat like the lamb, growl like the lion, whine like the seal.…

Much of Ryder—the bulk, even—consists of lists like this, by turns exhilarating and exhausting, “as if,” notes Paul West in his afterword, “[Barnes] were intent on producing La Brea tar pits of blather, just to get us in a primitive mood, amazed that humans could come to the Word.” Barnes’s authority may have been Joyce, but her primary model is surely Robert Burton, the 17th-century divine whose Anatomy of Melancholy established the art of the list in English prose.

Gutkin goes on to say, rightfully, that “Ryder is a tissue of digressions.” But poets know that digression often rides alongside the most dexterous of observation. It’s a treat to have such delightful prosody considered.

More info on the book is here.