The New Yorker Looks at Lucretius

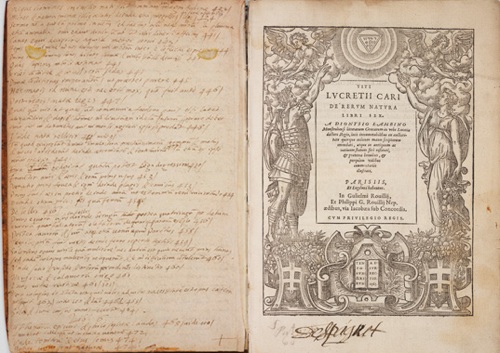

This week's New Yorker looks at Lucretius' two-thousand-year-old poem "On the Nature of Things" (the full piece can be read in the print issue), which has influenced poets as varied as Joan Retallack and Lisa Robertson. Writer Stephen Greenblatt discusses how the Roman poet was saved from obscurity (a copy of De Rarum Natura was found in a monastery in the ninth century and managed to escape fire and flood until it was discovered again in 1417 by an Italian "book hunter" and scriptor for the Pope). He continues:

Lucretius, who was born about a century before Christ, was emphatically not our contemporary. He thought that worms were spontaneously generated from wet soil, that earthquakes were the result of winds caught in underground caverns, that the sun circled the earth. But, at its heart, “On the Nature of Things” persuasively laid out what seemed to be a strikingly modern understanding of the world. Every page reflected a core scientific vision—a vision of atoms randomly moving in an infinite universe—imbued with a poet’s sense of wonder.

Lucretius was an Epicurean, and so pleasure was key in his conception of things, but also interesting was his vision that "everything that has ever existed and everything that will exist is put together out of what [Lucretius] called 'the seeds of things,' indestructible building blocks, irreducibly small in size, unimaginably small in number," "atoms." Greenblatt notes how fascinating a find the manuscript must have been in a time when the Church was more interested in pain and punishment than pleasure:

This philosophy of pleasure, at once passionate, scientific, and visionary, radiated from almost every line of Lucretius' poetry. Even a quick glance at the first few pages of the manuscript would have convinced Poggio that he had discovered something remarkable. What he could not have grasped, without carefully reading through the work, was that he was unleashing something that threatened the whole structure of his intellectual universe. Had he understood this threat, he might have said, as Freud supposedly said to Jung, when they sailed into New York Harbor, "Don't they know we are bringing them the plague?"

Read the abstract here, or pick up a copy of this week's New Yorker at a small bookstore.