Climb Up Sure But Do You Know Where You Are Going

BY Kazim Ali

Israeli settlers are apparently entering the grounds of the Temple Mount and climbing on top of the structure of the Dome of the Rock. When I went to Israel, we entered the grounds through various of the gates in the eastern part of the city. There were Muslim caretakers at these gates and to ensure that those entering by those gates were worshipers and not tourists nor trouble-makers (and there has been trouble in that space—violence and vandalism) those passing through the gates are asked questions pertaining to religious knowledge, sometimes asked to recite certain verses from the Quran. You have to know or you don’t enter.

There is another entrance to the place. It is a security checkpoint in the Jewish Quarter just next to the Western Wall. You go through a metal detector, your bags are searched and you climb through a little covered causeway to Mount. There, among others, are the Far Mosque, built in the 15th century or thereabouts and the fantastic Dome of the Rock. Inside that structure is, indeed, the Rock.

It’s an odd piece of real estate. I saw rocks as huge in Hyderabad, where an ancient mountain range has, over the course of 70 million years, been shattered to pieces. This rock is either the place Adam and Eve entered the Earth after expulsion or it is the place that Abraham took his son to be sacrificed, said son being either Ishmael or Isaac or it is the place that Prophet Muhammad was brought to on his night journey from Mecca and from which he launched up into heaven.

And/or, to be sure, it is a rock.

In any case, no one is allowed to climb up on it though you can—if you are Muslim or if you at least know some verses to recite or go along with someone who can bring you in—climb down inside it into the so-called “well of souls.”

I went down inside it. What I saw there, softly illuminated, that that space was like, I will not say. We keep secrets and some secrets, they keep us.

But who owns a place? What is a nation? A place of common language, common origin, common cultural values and structure? What is it meant for? To protect you, to promote your economic or religious interests, to guarantee you access to natural resources? Empires were founded to bring from far places spices, vegetables, metals and minerals. But really, I want to know, it isn’t a rhetorical question: who owns a place and why?

One of my favorite scriptural stories is about the king Nimrod who decided to a build a tower to reach heaven, which is only an interesting place because god lives there. Of course, as the story goes, God cursed the builders by fracturing their language so they could no longer communicate with each other to build—the origin of poetry was the human urge to actually reach the geography of the divine. What are the implications of such thinking? Was the poetry a curse or a gift, an answer to the urge to build that edifice skyward?

When I went to Jerusalem I found oddly touching and ominous the entrance to the Mount near the Western Wall. In the first place, the small plaza in front of the Wall was completely impromptu—plastic lawn chairs pulled up next to it so people could sit and pray. In the second place, on the causeway itself very neatly stacked—for quick and easy access one supposes—were scores and scores of riot shields. And anyhow, as my friend who lives in Israel, a religious Jew, tells me, one of the names for God in Hebrew is “the Place” so why is it we end up taking any place at all on earth as sacred. There is no road to heaven. Ask the builders of Babel.

The divine must live in the mortal world then. In her poem “After a Student, 15, Declares He Will Renounce the World for God,” Kathleen Graber has the forsythia bush speak: “I’m forever. I’m all the evidence you need,” it claims. And of the tower of Babel, she dreams of being one of the builders, thinking, “how the gods must stop here/ at their own reflections.” All we have at the end, is our “beautiful confusion.”

Living in the world, embracing that confusion, means using the body to understand the spirit. In her poem “Love Isn’t,” Pat Parker confesses, “I wish I could be/ the lover you want/ come joyful/ bear brightness/ like summer sun// Instead/ I come cloudy/ bring pregnant women/ with no money/ bring angry comrades/ with no shelter.” There is no separation in Parker’s reality between caring for the individual and being concerned with larger issues of social justice. “I care for you,” she says to her lover, “I care for our world/ if I stop/ caring about one/ it would be only/ a matter of time/ before I stop/ loving/ the other.”

Parker’s insistence on the inseparability of both concerns may feel anachronistic in 2014. Consider Amiri Baraka’s criticism of Angles of Ascent, the recent Norton anthology whose jacket claims of its contents, “These poets bear witness to the interior landscape of their own individual selves or examine the private or personal worlds of invented personae and, therefore, of human beings living in our modern and postmodern worlds.” Baraka called it “embarrassing gobbledygook” and “imbecilic garbage,” saying, “You mean, forget the actual world, have nothing to do with the real world and real people ... invent it all!”

Parker views such a practice—the examining of an interior landscape without also engaging in historical and material context—to be a form of madness. In the foreword to her powerful book Jonestown and Other Madness Parker writes, “I must ask the question: if 900 white people had gone to a country with a Black minister and ‘committed suicide’ would we have accepted the answers we were given so easily?” She creates a critical confluence between our ability to either engage or disengage from issues of social injustice with the bodies that are victim of such injustice. The 900 black bodies at issue—the people who went to Jonestown and drank the cyanide-laced juice and died there—seem then to be irrelevant, less worthy of concern. Audre Lorde talks about anger at injustice as a genesis for creative expression when discussing the origins of her poem “Power”: "A kind of fury rose up in me; the sky turned red. I felt so sick. I felt as if I would drive this car into a wall, into the next person I saw. So I pulled over. I took out my journal just to air some of my fury, to get it out of my fingertips.”

There was a case, in Nevada in 1980, of a woman who, rather than find expression, succumbed to such anger. Priscilla Ford drove her car off the road into a crowd, injuring 23 and killing 6. Though expert witnesses testified that she was suffering from a variety of mental illnesses, the judge and jury believed her competent and able to tell right from wrong and sentenced her to death. Parker writes of her in a poem called “one thanksgiving day,” “You cannot be insane/ to be enraged is not insane/ to be filled with hatred is not insane/…/ it is your place in life” and went one to say, “The state of Nevada/ has judged//that it is/ not crazy/ for Black folks/ to kill white folks/ with their cars.”

Baraka famously asked for “poems that kill,” poems that could confront boldly the real lived conditions of people’s lives. I found such poems in the work of Lucille Clifton, who did not in any way shy away from embracing a Black aesthetic and going so far as to say “white ways/are the ways of death,” even using the word “europe” in one of her poems, “the thirty-eighth year” as a synonym for “death.” In the following short poem about Little Richard, she similarly uses the word “faggot” ironically while defending Little Richard’s sexuality and non-conforming gender behavior:

when a whitey asked one of his brothers one time

is little richard a man (or what?)

he replied in perfect understanding

you bet your faggot ass

he is

you bet your dying ass

For me the beginning of nations—the beginning of our separation from one another, the beginning of the rules of gender and sexuality that would come to govern how wealth was transferred from generation to another through stuctures of inheritance—is antithetical to the life of the individual human life and spirit. And me? My sacred place is no Rock, no remnant of a wall of a temple which hasn’t existed for a thousand years. Rather it is my favorite kind of church—the wide empty and interactive space of any museum where paintings hang or any place poetry is recited or dance is performed.

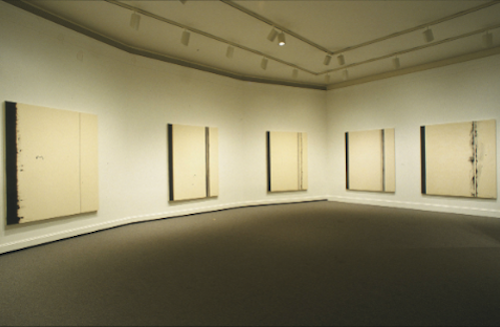

Last year I climbed up into the so-called “Tower,” an exhibit space in the National Gallery of Art to see the series of paintings by Barnett Newman called “The Stations of the Cross.” Newman himself used to talk about the place a painting hung as a “makom,” Hebrew for “place,” with all the connotations of a sacred place. Harry Cooper, the curator of the show, wrote, “the Stations might seem to raise the question 'Where am I?' Is my proper place in front of each of the paintings, one by one, or walking by them, or turning around in the middle of the room to try to take in the series as a whole? For that matter, am I in an art gallery at all or, as the title suggests, passing the Stations on the road to Calvary?”

There’s no answer to the question. I went along the Via Dolorosa myself when I was in Jerusalem, or as much of it as I could. The first station is inside a private building. The end of it is inside a church, of course. But someone north of the walled city in East Jerusalem, just across from where all the taxis to Ramallah wait for their passengers, is a smaller garden which other’s claim is the “real” site of Calvary. Who can say?

It makes no difference to me. Mosques are empty inside, being just four walls that organize a space in which worshipers gather. There’s no there there. Olga Broumas writes about it in her poem “Diagram of an Abandoned Mosque”:

1 The loggia circled by mouths of sleep

2 We startle leaving the garden

3 Medallions of traffic and steel

4 But phantoms

5 Of circulars evolved by blood

6 Ripple orgasmically still as though power

7 And architecture were not one

But power and architecture are one, after all. The architecture of a building and the engines of financial, political and military control are not at all unrelated. Of the men and women who went to Jonestown, Pat Parker says, “they didn’t die at Jonestown/ they went to Jonestown dead/ convinced that America/ and Americans/ didn’t care.”

“On a day when i would have believed/anything,” writes Lucille Clifton, in her own poem about Jonestown, “i believed that this white man…was possibly who he insisted he was.”

Newman gave his “Stations of the Cross” paintings a subtitle: “Lema Sabachthani”—“why did you forsake me?”—the cry Jesus launched up at God as he died.

And what are the stakes then? “If i have been wrong, again,” Clifton’s speaker at Jonestown goes on to say, “may even this cup in my hand turn against me.”

“This is the Passion,” Newman said,” “Not the terrible walk up the Via Dolorosa, but the question that has no answer.”

Poet, editor, and prose writer Kazim Ali was born in the United Kingdom to Muslim parents of Indian ...

Read Full Biography