The Winter of Our Disco Tent

“...the terrible and noteworthy irony...”—H.H. Bancroft.

New York City during the war years was, unless you were eating sushi with the Simics, a dark and horrible place. It was as if someone had loaded a leaf blower with copy toner and gone postal. Some of it got onto the 9-pound models’ eyes and they didn’t even blink. The streets seemed to sparkle with well vodka siphoned off from sensory depravation chambers. Today Brooklyn dates Paris 1919 (or is it Beirut 1980?) but in October 2001 it was a place where you could be disappeared with your dry cleaning by peachfuzz secret police and held indefinitely in a black closet a hundred feet under the Cosby house with no trial, no lawyer—not even a word to your mother—all because you looked like an Aztec rabbinical student. It was a strange day when you could actually point this out to a friend and fellow poet while crossing the Brooklyn Bridge in a tinted gypsy cab and receive a big shrug. After all, that was terrible, but that was that.

Which isn’t to say the war is over, and not as if the starting gun was a box cutter on a jumbo jet—it’s an endless war, right? Born to the endless night. Bush’s endless war, Obama’s ebbless war. But I’m talking about the early years, between September 11th and W’s reelection in 2004, when everyone was quite sure the war was on, and in fact, there was a lot of bragging to be done by wounded giants, and a double dash of braggadocio dissent.

No matter where you came down on the issue of incinerating future shoe bombers in hand-me-down sweaters on their way to kindergarten, who could deny the war had our names and a nickel to pay for the dance? On a prime number the war would have been a masked rider and cutter-downer to subprime—far from choice—brain steaks. It was a ghost tax on cooler heads. It was as if Kenneth Patchen’s unborn son grew up to be the voice of the NYPD’s anonymous tips hotline. Every rogue Wheatie (Wheaty?) flake clunking on hotel china was a little landscape of Iraq. Every heartbeat of every subway ride was a crash course in the war bans: Because writing poetry may be a lot easier than it is (stet) but there are certain experiences that do skunk the muse, such as when you breeze onto a subway at 7 in the morning and everyone’s spinning in Wonderland teacups reading the same New York Post with a picture of a cattle-prodded Saddam Hussein eating Cool Ranch Doritos on the front page. While it might be true that the poet is a maladapt who sets out to get in the way of some experience—any old experience—every poet I grew up loving or hating is going to dance clear of those fucking teacups.

I know what I wanted. I wanted John Ashbery to don poppy robes and light himself on fire in the middle of Millennium Park—me and Edwin Torres could beatbox. I expected young poets to dig mole tunnels under the 24/7 war mechanix bum rush then pop up in Pentagon crypts smoking more eyeliner than Geraldo. When a congressman wept while history waxed his ass, I looked for a poet to barf cut jewels into his saline pools. I prepared myself for Ginsberg’s revolution of the sexy lamb—and, under the circumstances, I expected ritual slaughter of that lamb on Wall. As far as I was concerned, 2003 was endgame for the American revolution, and the only place to go was into the wild woods of radical egalitarianism. Who was going to sing the campfire songs? Guess who.

But somehow that never seemed to happen. Though I might have just blinked and missed it. Because one thing about poet weather is that its storms come out of nowhere and sleep fast. No sandman can get his thumb on the fronts. A tropical tizzy within the international avant garde is rarely traced to a poet flapping her wings on a barstool in Milwaukee. The only real broadcaster of events in the poem is compulsory telepathy among poets, and the signal is often weak—disrupted by things like errant badminton birdies and popcorn drones. In order to stay sane as a poet during an endless war you have to assume that other poets are writing absolutely dropdead poems all around you, and in Tanzania, too, and you have to be OK with the fact (in fact, thrilled by it) that while you may never hear or read the actual poems, their radiance is chasing the globe like a sort of tantric atomic fallout.

Why don’t Pablo Neruda’s poems go on forever?

A: Because his lines keep Stalin.

Snapshots of the aughts. Dark, fragile, fragrant nights ... like the long-distance cigarette ash in that poem by—I think it was Rene Ricard—that I read at the bar in the Bowery Poetry Club, brainchild of Bob Holman, the ash itself like Jenny Olin’s sparkling leg as she daydreams the nocturnal reconnaissance of Union troops in the Lite-Brite whiskers of Walt Whitman’s beard nesting above the stage. Taylor Mead is on the mic,

his 52 cats twining themselves around the beer taps, living scarves escaped from one-armed bandits. Bingo Gazingo is threading through the smattering of midnight poetry junkies with a tottering stack (android pancakes) of deeply scratched CDRs of his sonic hits. “Mariah Carey! I wanna crawl into your ovaries!”

Remember Taylor Mead in The Flower Thief? 1960. Forty years later Ron Rice’s silver streets ran CMYK and John Coletti—still sporting a Tom Waits pomp—skedaddled up Avenue A. clutching a dripping bouquet of flowers:

“Hey, John, what’s the skinny?”

“Oh man!” darting a glance over his shoulder. “I just hotted these flowers.”

“You wha?”

“Hotted these—” John was breathless. Radiant with snorkeler’s glee: if you’d twirled a buttercup under his chin his skin would’ve glowed. “—flowers! I wasn’t gonna, but...”—he dashed for Tompkins Square.

“Hotted?” said my friend as we continued on our way.

“He’s a poet.”

Who did Mayakovsky meet on the Road to the Deep North?

A: Dharmakovsky

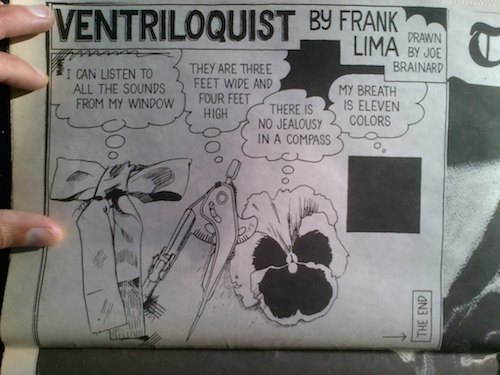

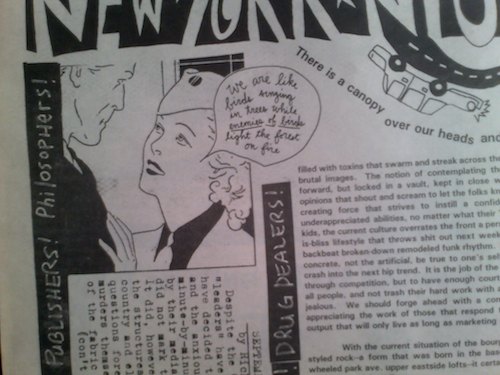

A little blurry, and sorry for the red eyes, but here’s one of 2001. Late Fall. Jeni Olin is reading at the KGB bar with Jordan Davis and Larry Rivers is in the audience with his friend Harrison Ford. KGB is Air Force One! I’ve asked the pressman at Linco to hit the cover of New York Nights #2 with extra ink to make the speech bubbles glow:

Jordan and I have a great mutual friend in Greta Goetz, but when I try to hand him a copy of the paper he doesn’t want one: “I’ll only lose it.” I pass it to David Kirschenbaum who contacts me a week later asking what printer I’m using. He’s thinking of running a Boog poetry anthology on newsprint. Three weeks later the first issue of Boog City hits the stands—featuring all of the NY poets who haven’t contributed to my paper. Milquetoasts! Jeffrey Joe Nelson writes in: “Did you hear those Boog Lit folks have got a fire lit under their ass by your NYNights & are now putting out weekly of their own to be released at party on 20th?” I email David to say he’s a “scene-conscious asshole.” Pot kettle black. Jordan weighs in on his blog: “What's Julien so angry about? As if anybody who's persisted past the annoying going-unnoticed phase of writing doesn't know.” Meanwhile, I’m trying to convince Linco to cut me a price break for throwing them Boog City—whose circulation combined with New York Nights' would have probably run short at an anarchist barn dance.

Cedar Sigo was close friends with Jeni and he’d put me up to going to the reading—which I hated. It took me a minute to see how great she was. No one else’s poems were anything like hers. They got onto your skin and your reaction was based on your personal poetic histamines.

Jeni was staying with Larry Rivers at the Chelsea Hotel, and Matvei Yankelevich and I went to meet her and Cedar there to interview each other about poets living in hotels: Both Cedar and I had done time in SROs, so the Chelsea was some pumpkins. I don’t know if Oscar Wilde ever set foot in there but I swear I saw him changing the lobster bib on the Mobster of the Opera in the WC Fields. There was a nude portrait of Jeni by Larry Rivers hanging over the bed. My apartment had just burned down, flooding a glass shop underneath, and I was carrying a package of “slightly irregular” tighty whities that I’d scored at some 99-cent store. Jeni glanced wistfully at the package and broke it to me gently.

“Those aren’t gonna fit.”

She once gave Cedar a book—was it Many Happy Returns?—signed by Ted Berrigan to Larry Rivers. She’d gashed out the inscription then signed it her own way: “Love, Bitch.”

You can visit Todd Colby’s blog to see a picture of Jeni and Cedar at the Chelsea: http://gleefarm.blogspot.com/search?q=jeni+olin.

She was really beautiful, I mean beautiful through and through, and a great poet in the self-making. I haven’t seen her for years but she’s still perambulating, if a Sphinx can perambulate, in the absolute elsewhere of the early aughts in New York. And it would be my honor, at some fork in the road up ahead, to hit the low notes behind Jeni Olin, John Coletti, and Taylor Mead in a LES barbershop quartet called The Flower Thieves.

Julien Poirier grew up in the San Francisco Bay area and was educated at Columbia University. He is ...

Read Full Biography