On Sunday night I found myself sitting down to dinner beside the Korean artist Kim Beom. At this moment, I did not know that I was already acquainted with his work. We talked about architecture, teaching, his family and his youthful appearance.

In Kim Beom’s video, titled: A Rock That Learned the Poetry of Jung Jiyong, a young woman reads a lecture about the poet Jung Jiyong to a rock placed before her.

Rock, woman, poetry, poet, Jung Jiyong, lyric, history, language, reading, art, education, subject, object . . .

I find my thoughts drifting to The Story of the Stone (often known as The Dream of the Red Chamber), an eighteenth-century Chinese novel by Cao Xueqin. In this story, a stone, deemed unfit to repair the heavens by the goddess Nu-wa, is left to wander listlessly in the city of Red Dust. A pair of monks pass Greensickness Peak, where the stone lay passing its days in sorrow and lamentation, here—detecting its intelligence and admiring of its physical shape (having been sculpted by the goddess, the stone is endowed with transformative powers: once a roughly hewn building block, it is now a translucent pendant)—one of the monks slips the stone into his sleeve.

Eons pass. A Taoist named Vanitas, in search of immortality, happens to pass Greensickness Peak. He sees a large stone (there is a rock in the Yellow Mountains they say is this stone, called: The Rock That Flew Here). The stone bears a long inscription. We are to imagine that this inscription is The Story of the Stone, detailing the account of its brief life as a human, before attaining nirvana and returning to Greensickness Peak. The Taoist reads this carefully and what follows is a conversation between the Taoist and the stone about the questionable merits of publishing the inscription as a book. A comical debate about genre ensues and the Taoist, rereading this inscription a second time, copies it down before setting off with the text to look for a publisher.

In the eons we cannot cover, the stone was housed in the Court of Sunset Glow, where Disenchantment lived, and where it befriended the Crimson Pearl Flower, which it took to watering everyday. Doing so gave her consciousness and she shed her vegetable shape. Her debts to the stone, she lamented, could only be repaid by mortal tears—if only they were both “reborn as humans in the world below!” And before long . . . (a courtesy of Disenchantment) . . . down they went, to “take part in the great illusion of human life,” which begins when Baoyu (our protagonist) is born with a piece of jade inside his mouth. As we cross the Land of Illusions, over the archway it is written:

Truth becomes fiction when the fiction is true

Real becomes not-real where the unreal is real

In the cosmology of the Stone, where Void is Truth and Form is Illusion, we enter a rather dystopic Rubicon, which (in some ways similar to Novalis's blue flower) gives us an allegory of the education of spirit, wherein the lifespan of the stone corresponds with the lifespan of our reading . . . both infinite, self-effacing/self-faceting mirrors, ill fated for this clarity of seeing doubly.

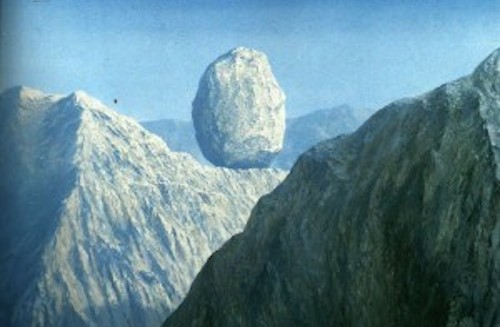

Last week, walking quickly through the Magritte collection at the Menil, I stopped in front of a pasty blue-gray rockface and looked up to read this quote: “A stone which does not think, thinks the absolute.” The projective imagination of the Surrealists gave us technologies to extend the subject into uninhabited realms to record the mind as it wanders . . . the charm of automatic writing, reuses the Romantic handkerchief, blowing their nose to see on the inside. But the terror of this psychic dispatch, this thinking that worms its face into everything, is that it can never reject its subjectivity as a (perhaps the) source of power.

Of course, the purpose of Surrealist exercises was (unlike the Romantics, esp. someone like Goethe) never about understanding its objects. It was never about thinking the absolute—or, thinking, in any traditional sense, but about enhancing the power of the subject. In a Magritte painting, for example, the stone is not a stone, but clothed by a kind of language. It belongs to a whole symbolic universe.

But I had forgotten that Magritte painted so many stones. Often, his stones float, providing contrast to a singular cloud by erasing its own density. At times, they embody a pair of fruits (a pair of pears, a pun!) . . . some kind of irrational petrification, in which the stone retains its psychic power. There is a painting, in which we find the stone nearby an open window . . . as if contemplating its own nature, of which it is at once a part, and not a part: this discursive interior, where language enters to draw the curtains . . . how to make this bearable?

Kim Beom, I have to concentrate. I stare at the rock, at the resisting-tenor of its own material, its thingness—its power to reject education, language, voice, to not be able to serve as a container for lyric material . . .

And yet . . . it is not about indifference. There is something incredibly tender about Kim Beom's rock, which is its mythic quality: this time of reading. Being read to, over time, we begin to imagine in the rock a kind of consciousness opening. Likewise in The Story of the Stone, we find a world-wearied sadness tied inextricably to this double-vision of reading (enchantment/disenchantment). But what is reading? We should really start from the beginning. And I should be reprimanded for the distinctions I have not made between stones and rocks! But there is no time.

Another time.

Also, I cannot seem to find Kim Beom's rock video online, but this is the video I fell in love with before our meeting, a piece called: Scream Painting.

If you happen to be in Houston this week, you can see A Rock That Learned the Poetry of Jung Jiyong at the MFAH.

Born in Shanghai, poet Lynn Xu earned a BA from the University of California at Berkeley and an MFA ...

Read Full Biography