DAMMIT FRANKIE. On Ryan Eckes's Old News

In which I talk about reading Ryan Eckes's Old News and Ryan talks about making Old News

Divya: Reading Old News

Philly’s poetry scene has had more than its fair share of interesting Franks and frank-related incidents—Frank Sherlock; CA Conrad’s Book of Frank; the bar for poets Dirty Franks; Benjamin Franklin; Barbara Cole’s situ/ation/come/dies which has a pretty epic treatment of this one hot-dog. And now, Ryan Eckes’ Old News has added to this genealogy the mysterious South Philly character—and all round asshole—Frankie:

originally

when i first met Frankie he asked where i was from

we stood in the middle of the block, facing my

new rowhome

well we moved from 10th and spruce, i said

they used to call that the tenderloin, he said

i actually grew up in northeast philly, i said

that’s where i’m from originally, way up in bustleton

i remember when that was just woods, he said

i remember when they built that all up

i said yeah, my grandfather built his house up there

still plenty of woods, though, if you think about pennypack park

he said, pennypack park, no, i don’t think about pennypack park

i laughed a little, said oh yeah, what do you think about?

he looked at me, unsmiling, then looked at my house.

Dammit, Frankie. The last time I disliked a random dude in a poem was when I remembered that unnamed guy with the “piercing pince-nez” in Ted Berrigan’s The Sonnets, or maybe the fat butcher who comes on too strong to Joe Brainard in I Remember. These men were comported by the poem, made ruddy or ridiculous by the verse’s deft sculpture. My fantasy of knowing Frankie (and loathing the jerk, but sort of wanting to meet him) is a pure product of the poetry’s shunt between what seem to be real conversations taking place on a stoop or in front of Esposito’s Meats in the Italian Market, and imaginary conversations with the dead and buried Philadelphians exhumed in Old News. Frankie is a cipher for every cross-generational conversation most of us are too chicken to have on a Thursday afternoon with our (potentially) born-again, (potentially) bigoted, (potentially) xenophobic neighbor whose best friend is a cop and “doesn’t mean to be a racist, but.” As such, Frankie is eternal—we will always be not really having that conversation with a guy like him. So, thank goodness Old News will.

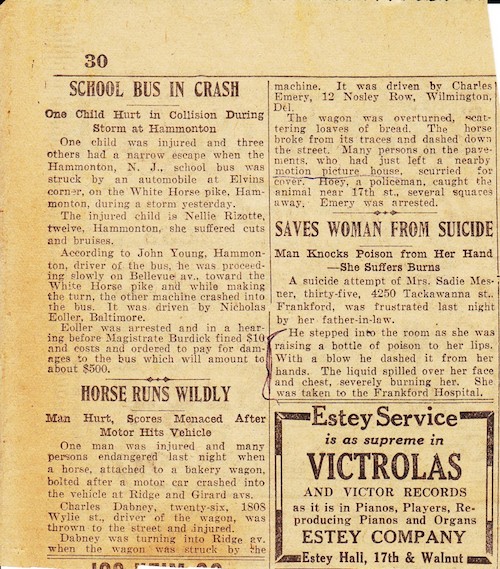

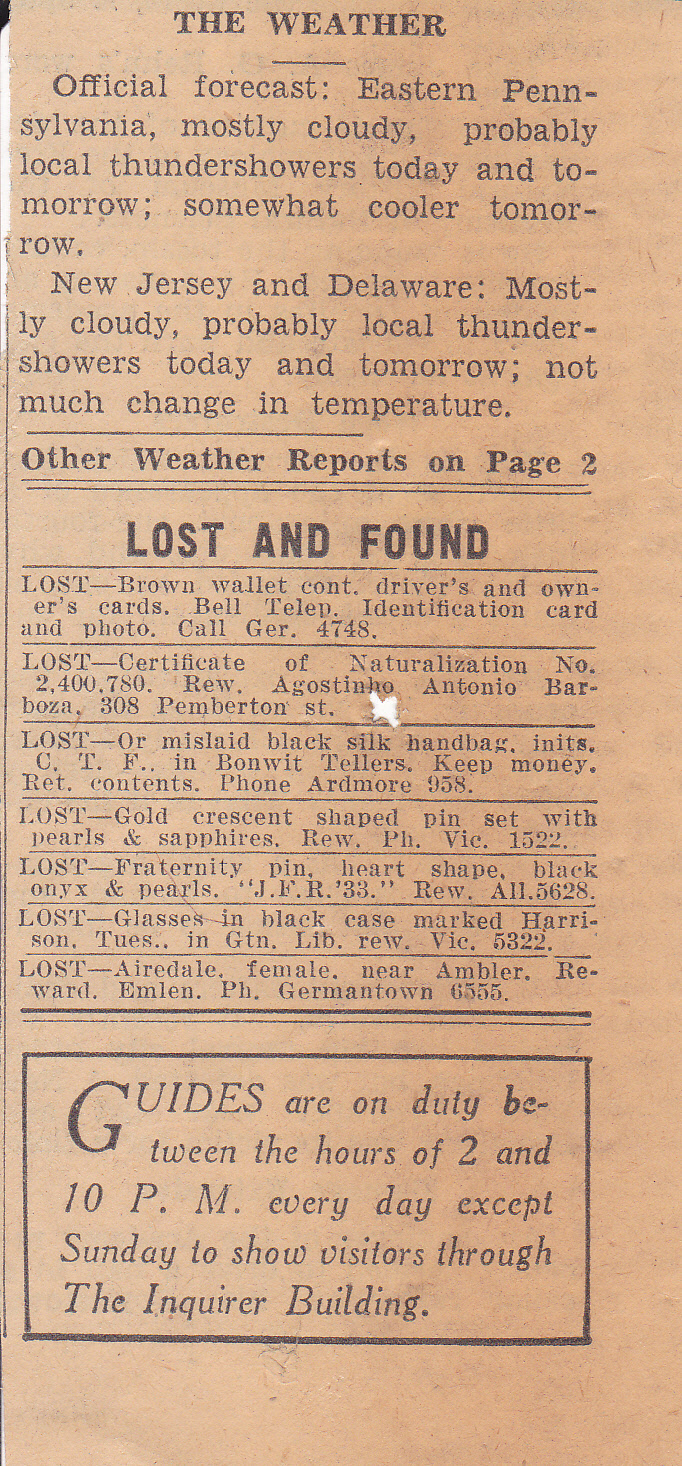

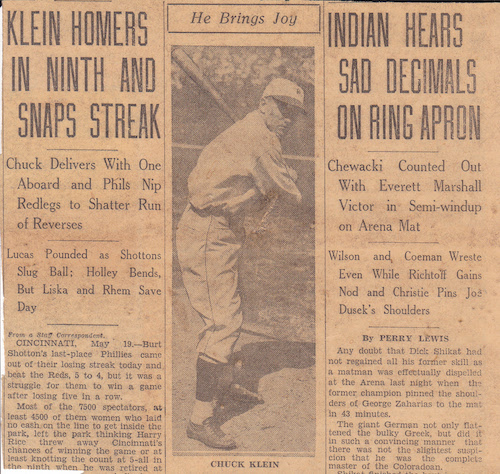

Ryan’s book of poems, composed between the springs of 2008 and 2009, is an effervescent archive of old news in the process of becoming new news. In ways that recall Charles Reznikoff’s methods for Testimony: The United States 1885-1890, Ryan clips and trims yellowing copies of The Philadelphia Enquirer and Evening Bulletin from the 1920s that were used to line the pine floors under the "rotten carpets" of his new (old) home. When you sweep things under your carpet, someone is bound to find it—whether in the annals of the National Reporter System as Reznikoff did, or under the musty carpet of a South Philly rowhome as Ryan did. When L.S. Dembo asked Reznikoff in an iconic 1969 interview “But doesn't testimony as such come out as simply a transcription of reality?” dear Reznikoff insisted that “[he] threw out an awful lot to achieve [his] purpose.” “It's not” he admitted, “a complete picture of the United States at any time, by any means.”

Neither is Ryan’s a complete picture of Philadelphia, which plays a significant cameo in the book’s treatment of racial anxiety, masculinity, gender politics, and cheese steaks. The city silhouettes lean and clean poems that advance the New York/ Frank O’Hara lineage of “I do this I do that” poems towards “I do this, I do that, and then I run into that bastard Frankie” poems: a significant and necessary torque in the poetics of The City [also] of Brotherly Vexation.

I read Old News and am called back to late night scenes during my years at Temple—the booth covered in paperbacks (?) at Dirty Franks on 13th street, the post-reading gossip smoke—which take place after all the stories you thought you already knew have been told and re-told, and then there is a pause and that one guy starts “this one time…” That guy is Ryan. Old News has made me draw the selected Berrigan, O’Hara, and Brainard from my shelves—and this is not just a coincidence. There is a cross-generational network here of men in big shirts typing about their day and sculpting really unremarkable, quotidian exchanges into Rube Goldbergian emotional dioramas—tiny epics that spiral out at cross-streets, while your pant cuff is caught in your bike’s chain and you’re late for a sandwich, again. How can anyone be late for a sandwich? Let these guys tell you. Even as Ryan’s poems are on the fine pages of a Furniture Press book, the poem, as O’Hara dreamed, is “squarely between the poet and the person.” Lucky Pierre. And lucky us.

I’ve never cared too much for reviews that claim that any poet is a master of some well heeled craft element—so and so is a master of the line break; boy, can he enjamb; oh, those internally hemorrhaging rhymes! I’ve cared some, but not enough to ever make public declarations about a poet’s craft per se. Assessments of craft seem to boil down to remarks on table manners by some particularly anglophilic Aunt—Can you chew your quail-egg without your maw hanging open like some unhinged barn door, son? Can you tell the difference between a beef fork and a lobster pick (one is four tined with the exterior two curving outward, and the other is two tined with a textured cylindrical handle, duh)? OK, now you can poet. While I (“I, personally,” as my students say) roll around in the inheritances of craft like a prize pig in 2000 count Egyptian cotton sheets—like, I get it—I have not always seen the need for the assessment of craft as the primary task of a review. (In this, I half-agree w/ O’Hara’s half-fake claim “I don’t even like rhythm, assonance, all that stuff”).

Having said all this, may I say: Ryan Eckes is a masterful wielder of stylized typographical emphases and the timely em dash that my cynic eyes did ever espy. If this were a white-space war, he would win with a single glyph and a raised eyebrow. Proof:

inside the scowl

i opened my front door this morning

to a big pile of dogshit

under the tree

recently planted for us

by the citizens alliance for better neighborhoods

and i cursed the italians

the big silent scowl

of those old italian men

who own the corner as

i walk by with my wife who’s not only

not italian but not white

(in this country)

and i thought of my italian grandmother

who grew up at 20th & McKean

go look at what the niggers done to it,

she’d always said, go see for yourself

and i thought of the letters

to the south philly review trashing

barack obama and i thought of my daily

rituals—joining the herd of other white people

after work as they spill out the east exit

of tasker-morris station while the blacks

herd themselves out the west exit and then

walking home along that border— how

ridiculous, i thought, this frustration we call

broad street—

these facts finally embodied for me in frankie,

two doors down. i overheard him giving shit

to the guys digging up the sidewalk

to plant our new tree—what’s that a cherry tree

it’s not gonna grow cherries, tho, is it?

i can’t help but imagine him, leash in hand, under his

breath, say you want nature you got nature . . .

but this pile of shit looks too big

for the little dog he walks up and

down the block and calls ginger.

ginger, did you shit on my tree?

In Old News, Ryan eschews the use of quotation marks to signal his use of borrowed voices—transcripts of diner conversations, notes stuck inside cabinets, confessions from mother’s mother’s mother’s letters—preferring, instead, the oblique italic, which is the typeface of the slightly titled head that’s always looking slant-wise and beyond the tall person in front of you in the movie theater. The italic has a Janus-faced effect: it has the all the typographic swag of the sarcastic badass, the stretched whine of the sticky child/Dorito addict, and it adds the stilted top-hat to upright text—it is, in other words, versatile. And Ryan’s insistence on italicizing all borrowed speech plays with this face’s repertoire. The effect is a crowded, chatty, many-throated and tight-knit series of poems that familiarize strange neighborhood characters—Frankie, Bobby, the cop, the roofer, the guy who looks like Gabriel García Márquez but isn’t, Rosanna, Clara—that is, it makes them family. And like family, we’re allowed to hate most of them, some of the time. (The poems, on the other hand, are decidedly unhateable—trust me, I tried my best).

The em dash in Old News seems its own creature—an entire lifeform that inhabits the verse and takes up space like that one guy wearing shorts and spreading wide. It gives the poems a lot of leg. The em dash here jostles tone and speech patterns with all the dexterity of a double-dot colon, helps to nest scenes within scenes like ironed-out brackets. It animates delay in the unfolding of language. The effect is distinctly hilarious and wry—wry as the driest Pilsner served at the Locust Bar on 10th—and reminds me of Ryan's characteristic comic timing: a way of waiting a fraction longer than most of us would, before disclosing something to your ear—an enviable skill he shares with another one of my favorite Philly poets, Frank Sherlock. The typographic minutiae here, of course, are just the superficial signs of Ryan’s ability to tell a story to your face right after downing that Pilsner without flinching once. There is no hemming and hawing here— no backward-glancing, speculative Once Upon a Time—there is only the now that is Philadelphia and the now that is the one time Ryan met a guy with his dog and he was an asshole (pronoun deliberately dubious).

Ryan: Making Old News

Old News was an attempt to write a little history of Philadelphia that was rooted in a block I was living on several years ago. I wanted to write a book about my neighbors that would include stories from old newspapers I’d found under the carpets of my house: pages from The Evening Bulletin and The Philadelphia Inquirer from 1923 and 1933. So the plan was collage, but to make the book a poem I’d have to not know where I was going. I figured if the book moved from page to page the way my prose poems had moved from sentence to sentence, it might work. With the prose poems, each sentence had to answer what seemed most at stake, most urgent in the previous by expanding the stakes, by raising more questions through intuitive leap (association or metaphor grounded in the reality of the circumstance described; not merely decorative). This would be the form of investigation. Each page would be a digression which added to the whole story; each page would build and build, arrive and arrive.

This process narrowed the possibilities of newspaper material that could work as I got further into the writing. From the huge pool of articles I wanted to use, few made it into the book, though getting lost in those old papers and drawing connexions between my neighbors’ daily problems and those from 80 years earlier pushed my thinking through the writing of the entire thing. I wound up more interested in the kind of news that wouldn’t make the news today, and the often strange detail and beautiful language within these stories. Back then, more was reported. I was struck by the number of stories on missing persons, petty crimes, car accidents, suicides and daily violence—common events which perhaps seem less so if they’re removed from public record. So I focused on these, letting them bleed into the larger political conflicts that the book takes on. Working with this material forced me to dwell on contemporary notions of human progress. And it left me with a humbling sense of scale.

Also, because there was more news fit to print in the 20s and 30s, there were often hilarious and striking juxtapositions. There were wonderful sports headlines and archaic advertisements I wanted to show people. Most of this stuff just didn’t fit into the book given the restraints I’d developed, but I did show it to my friends when they’d come over. I still have the old papers in a trash bag in my closet if you ever want to come take a look at them.

Ryan Eckes was born in Northeast Philadelphia in 1979. He wrote Old News from the spring of 2008 to the spring of 2009 in South Philadelphia, where he continues to reside. More of his poetry can be found in the book when i come here (Plan B Press, 2007), on his blog, ryaneckes.blogspot.com, and in various journals. Along with Stan Mir, he organizes the Chapter & Verse Reading Series. He works as an adjunct English professor at Temple University and other colleges.

Divya Victor is the author of CURB (Nightboat Books, 2021), winner of the 2022 PEN Open Book Award and...

Read Full Biography