Being Happy With The Ordinary, part 2

The economy is a big subject and “v. (economy)” is a masterful section of The Ordinary (Compline 2013). This mastery is created with the interesting technique of including self-doubt and a depth of thinking about the subject that verges on cancelling out its own conclusions, even as you arrive at them, more with the writer than as part of his audience. The reading experience here and elsewhere in the book is emersive, not unlike being in the economy, except that instead of getting royally fucked you find you are being supported in your efforts to work and resist. The title of the section opens the piece with several definitions of economy (emphasizing oikos house + nomia arrangment), then with a poem that sounds and appears, by its visual presentation, to be quoted. This poem ends

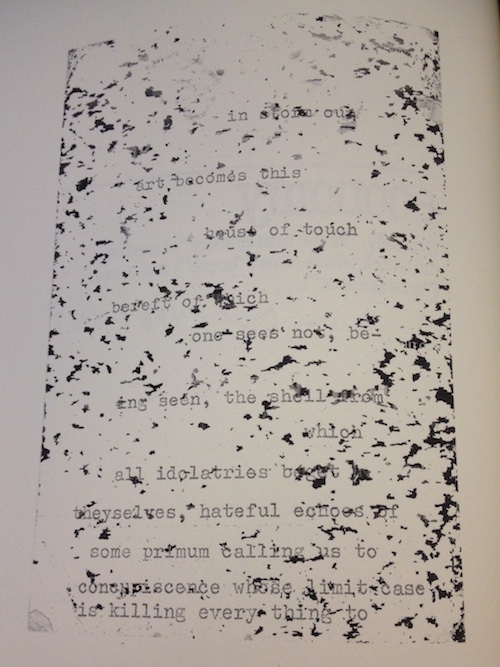

“all idolatries beget in/ theyselves, hateful echoes of/ some primum calling us to/ concupiscence whose limit case/ is killing everything to…”

On the next page we find a borrowed preface obviously reproduced from another published text which announces “The general concept behind this treatise is that of a paleogeographer. It is an attempt to combine classical and archaeological evidence with the results of sciences like agriculture, geo-morphology, soil-science, paleo-botany, etc. in order to obtain a deeper understanding of the interplay between man and his environment two to five thousand years ago.”

These several starts are followed by lines which begin (again) this investigation of the economy by examining the question of how to spend the time we have in our life while our own death burns inside of us every minute, always on the verge of its inevitable triumph.

Am I doing the right thing with my time ?

How to stir up potentials in oneself

We’ll think about the micro for a minute,

my participation, which is not yet

to worship the subjective though the

subjective may be the form in which we

can most grasp knowledge of that elusive

thing we wish to study.

(In what forms does it appear ?)

Economy is the economy of what comes

Down to sense…

On the facing page we find, have already found, what seems to be a reproduction of a page of a child’s work book: “Find the Building Material,” “Word Search,” “Word Box,” etc. It is ordinary and appears as the result of chance.

We begin our study of the ordinary situation we share with the writer by determining, with him, that with extraordinary effort we can get a view of this thing, this “economy,” we are in and which seems to determine much of what is possible. The approach is a lattice of assertions, questions, observations, partly direct and discursive, partly allusive and sound-driven but always arguing and investigating. This action occurs while also examining the problem of being complicit, lacking information, and being inconclusive, slothful and unable to continue but continuing anyway. Connectedness among texts and people is constantly sought. In any section there might be interlinked references to biblical, classical and Marxist concepts in a mix that is not peculiar to Brazil but which is particular to him. Within a few pages (CXIV-CXV) Laura Woltag appears, Kristeva comes up, “(Spinoza, and Hegel after Spinoza)”, Brian Whitener, Hosea, Paul, Toni Morrison and the movie Chinatown (“the future, Mr. Gittes”). There is a constant restarting and reexamination.

“Economy is posed as enigmata. As enigmata

Plaited, the shadows of which we know only by

It shadows…” (CXXII)

“Creatures having technical ability to/know what death is as a speculative fact we are obliged to decide with/respect to it, with respect most of all to its formal undecideability/within the space of this life.” (CXXIII)

Eventually the lines of the poem become so intensely prosodized that the phrases mean in many directions at once rather than moving in a linear progression, though they also continue to do that, even as the work atomizes toward the end, as it seems to come out of speech, remembered and imagined history, as well as a contemporary context of spirit, technology and war.

sign-on

sophia

click at the

bleed, there’s

only one

war

Two passages from the end comment on this examination of economy and one’s relationship to it.

“Anyone in debt will struggle just like you so sing it, for their benefit.

It’s not just a good idea. It’s the law.” (CXCI)

The imprecation to “sing it” brings us back to happiness. There isn’t that much to be happy about when considering the economy. It is in fact the least happy of considerations--grinding us up, as it threatens to do, in its iron jaws (as those of a leviathan). That “singing” is a help is so well demonstrated by the present song as to support a belief in continuing to resist in ways that can be sustained. It is the opposite of the experience I recently had reading a comment by George Oppen that he didn’t think he could have done the writing he did if he had to work at a job until retirement (notwithstanding his long silence.) The Ordinary is written in the context of ordinary (or less) time available to the author but with an extraordinary determination to utilize that time and information available to him in a way that engages his reader in a shared economy of love and faith. It’s often hilarious but rarely ironic. “Belief is the first gate on the path,” Brazil quotes and he believes it.

The ending passage, from Kant’s First Critique (“Second Analogy”), reminds us that “the house is not a thing in/itself, but only an appearance, that is,/a transcendental object/of which is unknown” but not, somehow here, more unknowable than any other thing. It a funny point where the actual solid object dissolves or the idea of it—resulting in an exploration of the origin of the word “economy” (“ecos” “house”) which everyone does who writes or thinks about the word but there is the Kantian twist that takes you down another path in the cultural labyrinth. A person could probably write a book about the difficulty of grasping the term or start a philosophical school named after objects, but Brazil moves on to close the section with an image from what appears to be a coloring book image of Disney’s Magic Kingdom.

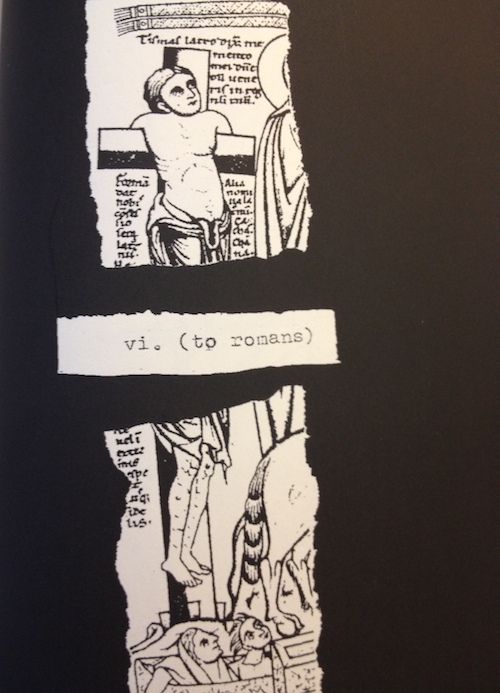

“vi. (to romans),” the last section of the book, begins with two torn pieces from the cover of crucified thieves and then goes on to a reproduction of a part of the crucifixion with what appears to be two apostles, shepherds, an audience in the distance and perhaps Mary standing on a cliff above. The print is by Lucas Cranach the Elder and is usually called “Allegory of Sin & Grace.” A text in German is printed below. The image is an ensemble piece that represents events over time. The next page contains only the line “…that bastard Paul… --SB”

This section is a translation of The Letter of Paul to the Romans, commonly called Romans, a book of the New Testament. Much else previously in the manuscript has related back to Paul and Brazil has continued to focus on Pauline texts in his work and study after writing The Ordinary. It is a vast area of study with a long bibliography, none of which is necessary to know to appreciate the poems in “vi. (to romans)” though, as usual with David’s work, the more you know the more fun you can have with it. My first time through this section, not being much of a Bible reader, I experienced the poems as a villanelle-like series with many repeated words relating to Paul. It didn’t occur to me that it was a translation. Despite my strange obliviousness to the obvious direct relation to “Romans,” (there are 16 chapters to the biblical book and sixteen poems) I did have some background, having read books by Georgio Agamben and Alain Badiou about Paul which left me with some sense of what was at stake with regard to Paul and the philosophy of the law, theology, politics and empire – to mention some of what comes up. Since then I have read Jacob Taubes’ book The Political Theology of Paul. You could obviously write many books, and certainly a longer essay, about these books and about this subject. The subject, as I see it, is how to be a person and a citizen with regard to the law and the empire and, further, how people in your community should exercise their freedom to believe as they do and follow the laws they believe in.

A useful way to proceed is to read The Letter of Paul to the Romans—there are many versions including one in the drawer of your bedside table if you happen to be in a hotel at this moment. This exercise will allow you to notice that instead of “father,” Brazil uses “dad,” “goy” instead of “gentile,” and, most often, “slave” instead of “servant.” “[L]ove” is the same, along with other repeated words “faith,” “truth,” “death,””grace,” etc. The poems are absorbing to me as poetry partly because I appreciate the peculiar concision of the wording and the Oaklandish diction: “Should we stay sinners to get grace ? / No way ! We who were dipped in Christ/ Were, baptized, buried in his death.” I also appreciate the long view of civilization that starts millennia ago and a sense of life which constantly includes death.

Paul believed that he lived in the time of the rapture or apocalypse, not because his world was in the sixth extinction event as ours apparently is, but because of the intensity of his faith. Catastrophes happened then, as they do now, and were worrisome to people then as they are to us. The Letter of Paul to the Romans is not Revelations but it has some of the millennial passion associated with that other book, written later. Taubes comments that with the letters of Paul “happiness and good fortune are…identified with passing away…with downfall!” (72) and quotes Walter Benjamin’s “Theo-Political Fragment:”

…the rhythm of this eternally transitory…worldly existence, transitory in it totality, in it spatial but also its temporal totality, the rhythm of Messianic nature, is happiness. For nature is Messianic by reason of its eternal passing away…

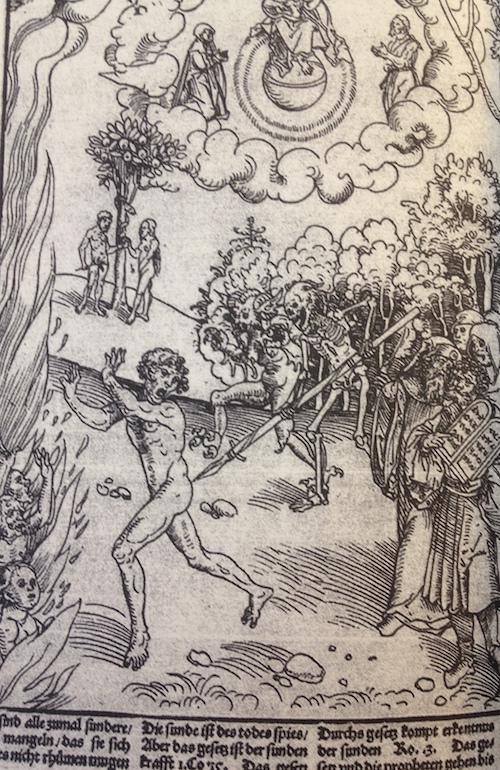

So we are left with a strange sense of happiness as, last line in the book, “Old secrets now are being shown.” One might say they are the same old secrets but revealed differently and according to the needs of our time, as we, with David Brazil, in The Ordinary, figure out how to live now. We examine how to be in the world given the vicissitudes of making a living, participating in political realities that demand a sustainable ethics, loving partners, friends and family, community and possibly even enemies and just making it through each day. Brazil’s approach is to elaborate and translate and examine and look for roots and put this all through the experience of ordinary life. He follows this practice to demonstrate the value (and just the fact) of doing it and because the practice comprises the extraordinary measures he wants to take, along with his reader, to get as far as possible into meanings, consequences and implications of every aspect of the ordinary. His diction and prosody are sophisticated, his matter and phrasing allusive and yet clear. There are a lot of funny parts. The farther you go with The Ordinary the farther you can get. The penultimate image is a reproduction of a print in which a skeleton uses a long spear to poke a naked man in the butt. Adam and Eve are in the corner with the serpent. Christ might be rising in glory in the middle top or it might be Mary (are those breasts?) The final image on the back cover is a continuation of the front cover depicting a never ending crucifixion event that is also a garden of delights, as if all of these biblical stories and other myths are always already going on and climaxing all around us.

Born in St. Paul, Minnesota, poet and novelist Laura Moriarty grew up in Cape Cod and northern California...

Read Full Biography