Brent Cunningham once commented that the books in his library were a kind of 3-D representation of his mind. These are the books that I’ve read—“the contents of my head”—to quote Annie Lennox. A personal library is proof and objective correlative of one’s relationship with certain writers and ideas. I agreed but knew that I could no longer sustain this vast Borgesian “universe, which others call the library…” in which everything I have read needs to exist in person. I thought then and know for sure now that I wanted to let the things, books and people that need to go go. New items required the space in my head and especially in my house. When, recently, I suddenly had to move, the situation became more urgent. Luckily, I had already begun to address this common poet problem of too many books, but let me start a bit further back.

When I moved in with Jerry Estrin in 1976, I was delighted to combine our two libraries, the intermingling of which represented the kind of intellectual sharing that was one of the things I was looking forward to about this shacking up, as they used to say. I loved my family but did not grow up in a house of books. I looked forward to living in one and then I did. It was paradise. Also present in this paradise were many jazz records and a few rock ones. I was so poor I didn’t have that much of anything to bring to the table, though strangely, we did have many of the same things. I still have two copies of Creeley’s The Day Book, two of Bashō's The Road North, various Ginsbergs and several Sapphos. My older Dylan albums are actually all Jerry’s and then when Nick Robinson and I got together in 1994 my Dylan collection was complete, with me maybe only buying Desire, the one neither of them liked.

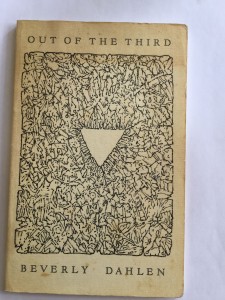

When I moved in with Jerry, I brought my Anaïs Nin and Virginia Woolf diaries, my Blake, my Whalen, my early Bev Dahlen book, with the William Wiley cover, Out of the Third, as well as my Scholastic Edition Jane Austen, Brontë sisters, Conan Doyle, and Jules Verne books (the last of these since discarded). Not that I don’t love these writers as much as ever, but I have either replaced them with new editions or realize I can rely on other libraries for them. Thank God, public and university libraries still exist.

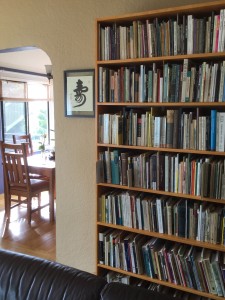

Books need to go somewhere, to circulate, to begin and end. There are too many books. It is one of the strange things about the “book industry.” People rarely ask if there needs to be another book before putting one into the world. Those of us who deal with books in a work capacity know that there are just too many. They can overwhelm your house or business or library. Happily, in our current house there are just the right number of books. They are in order. None of them are in boxes or on the floor. There is a special area for tiny chaps. It is the first time in my life I can make any of these statements (and it took a couple of years of work and that major move to bring it about.)

[Nick Robinson working on the library and the happy result. The framed character signifies longevity.]

I have only just started to appreciate this most recent version of my library, this new paradise. I say “my” library but it is “our” library. Most of the books are mine but my husband Nick Robinson is a librarian (and musician who is book-focused but less so than I) and the will to organize really started with him. Though I am the one who weeds the books in our house (to use the technical term) and I am merciless in my weeding, it was Nick who divided the books into boxes marked “poetry,” “fiction,” “ nonfiction” and “oversized” during the grueling days of packing and sorting before our move. And it was Nick who completed the alphabetizing of poetry and fiction, while watching TV and making appropriate comments about plot etc. The new delight of being able to lay my hands on a desired volume has deep roots in all aspects of my life. It is what I never understood about householding during my days of living in chaos.

But, there is a hidden problem. Not really hidden because located on Pierce Street near our old house in a storage facility in a very pricey little room. In this space, which costs three times as much every month as my first Berkeley rented room, are many boxes containing the archives of both myself and Jerry Estrin. (Nick's archives, those from Poet's Theater, are located in Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature at New York Public Library.) I am sure the archives in New York are housed beautifully but the room on Pierce Street is less elegant. The archives there are blocked in by suitcases, a rocking chair and a whole lot of general crap. There is a plan for organizing this material, involving another person doing it. I have learned through hard experience that it is almost impossible to organize your own archives. A decade or so ago, Patrick Durgin made a start at an odd time in his life where he was willing to sit in the pricey room for a few hours each day over a week or so to make a register which I, of course, lost but then recently found again during the move.

One of the reasons for this new organizing is my awareness of death. People close to me have died. They haven’t all been old. When you die you often leave behind a mountain of stuff creating anguish and organizational despair in those left behind. Having been through this more than twice I wanted to make some kind of sense of out my items—to curate, husband, organize, discard, present, clean, store and utilize each thing, especially each book, in as good a way as possible. It is a modest plan but one that’s strangely difficult to achieve.

The need for a beautiful library is universal. People aspire to them. Back in Albany I occasionally hiked on the Albany Bulb, well-known for amazing public art and determined, semi-hidden homeless encampments ("Punk Pirate Paradise" is a name painted variously on the Bulb) and I would encounter libraries, as the one below, which seemed to possess both a public and private aspect. It seemed okay to visit and photograph but not too often and only because signs (one is pictured at the start of this post) invited one in. I brought books there, as I did to the various ephemeral libraries that existed in Oscar Grant Plaza during the Occupy. There is a Little Free Library movement with many in Berkeley and El Cerrito and elsewhere. It’s a national thing. They look a bit like bird houses—with the idea of take a book, leave a book. They seem a little too nice, but that’s just me.

Libraries and archives are often threatened. Most librarians and archivists have had the conversation in which the person in power comes in, looks around and notes how much space is being taken up by this anachronistic entity and tells you why and how they are going to try to colonize it. As with other colonization, you can’t always win against these powers, but sometimes you do. But, win or lose, you have to get rid of some of the books.

When I was in fifth grade, in Otis Air Force base in Cape Cod, my class took a short walk over to the junior high (middle school) where there was a library or maybe it was just me wandering over there on my own. In any case, this small library was full of autumn light, big tables, and many books not yet read by me. At that point, I was twelve, I felt I had read all of the books in the Base Library and was having my mother drive me to the North Falmouth Library. I remember the white walls of this junior high paradise and the many books delectably presented. I couldn’t wait to go there but never did. Instead, we moved to California where I joined “library club,” total dork that I was, and enjoyed being able to be behind the desk and check out the books for other kids. Later still, in my book Ultravioleta, I imagined The Gutenberg, a destination hotel library satellite that orbits Europa, a moon of Jupiter. Ada Byron, concierge and head librarian there, wants to get rid of time but she can’t, not unlike me with books. “Finally, nothing really takes the time from Ada. Time surrounds her, opening out like a pit. . . Whole planets seem lost to time, but Ada is never not in it.”

As it turns out, a unique way to lose yourself in time and books is coming up soon. With 50,000 books donated from the Internet Archive, the help of Fluxus Foundation and a hopefully successful Kickstarter, a project called Lacuna will be—not exactly getting rid of books—but putting them into a sort of extreme circulation, by building a large temple made of books in which books will be given away. This will actually occur in Berkeley during the Bay Area Book Festival this June 6th through 7th. These library temple builders are using the word “lacuna,” which typically means the missing portion of a manuscript or book (the following is from their video about the project) “as a representation of that space we occupy when we’re deep in a book we love, when we’re lost and finding ourselves through reading, the way the world can kind of move around us as we sit deep inside the pages . . . ”

Paradise now.

Born in St. Paul, Minnesota, poet and novelist Laura Moriarty grew up in Cape Cod and northern California...

Read Full Biography