A Maxwell’s Candor Is the Brightest Shield and Peeping Mot: Notes and an Interview

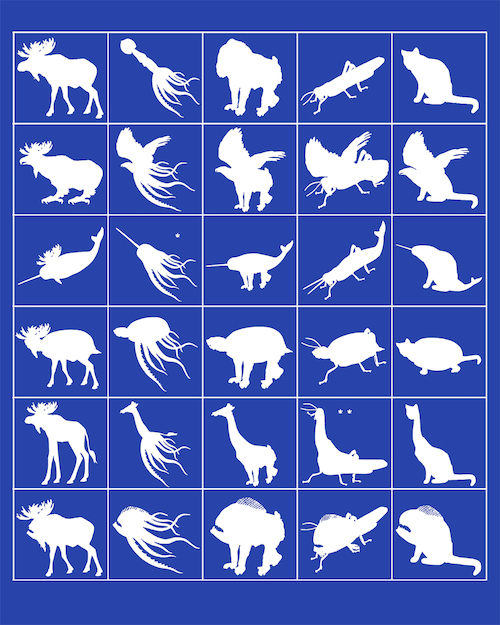

A Maxwell’s Candor Is the Brightest Shield is a beautiful book. As with all Ugly Duckling Presse publications it sits well in the hand and has a just right physicality. It also has stylish black pages between sections (especially useful if your author declines to paginate), perfectly chosen typography (Old Typefaces and Averia in this case) and a cover design that reflects the author’s taxonomic bent while satisfying the reader’s desire for something cutting edge and bright blue. Though Peeping Mot (from Apogee Press) does not get the full attention it deserves in these notes, I will point out that it is also a lovely publication with irresistible cover art “O” like a bird singing, just for itself by Erika Lawlor and use of multiple colors of type, a handy as well as attractive design element. Maxwell is truly lucky to have two such gorgeous books.

It is possible that Candor Is the Brightest Shield can be seen as beautiful in another way. Here I thought to use the old notion of the beautiful and the sublime by suggesting that Candor exists primarily in the realm of the beautiful. Reading Edmund Burke as a kid and later puzzling through Kant as a grown-up piqued my interest in these categories, though, to be honest, my attraction to them seems more like astrology than philosophy. I had an email exchange with A Maxwell on the subject and realized that what I meant to suggest by referring to “the beautiful” in relation to his writing is that Maxwell engages his reader with reasoned, subtle arguments that persuade not only with logic but with unique, occasionally oblique, turns of phrase, puns, musicality, and, well, love. But then, what would it mean if writing could be said to be sublime rather than beautiful? Perhaps sublime writing would evoke fear in some way, terrifying and endangering the reader, taking them where it might not be good for them to go. But, I realized, the book does this as well.

Candor Is the Brightest Shield proposes what I would call a taxonomic or indexical sublime (the phrase “ruderal sublime” occurs as part of the epigraph page in Peeping Mot). In Candor, these sublimes rise from an attenuation of ideas into an almost infinite set of propositions in a diction that is multi-syllabic, achingly anachronistic and yet also disturbingly contemporary, possessing as it does the possibly dangerous knowledge of one whose day job is taxonomist and manager of classification and machine learning initiatives at Google. “[R]uderal” refers to disturbed land, essentially the wasteland. Maxwell’s affection for what is vexed by people and civilization, whether taxonomically or by rows of corn (or verse), is an interest that many share, causing his practice to be urgent to those of us (everyone) who occupy this disturbed ground.

Addressing my question about his sense of, and interest in, the concepts of the beautiful and the sublime, Maxwell commented,

I always think of the beautiful in terms of an argument, or of the argument at hand. The "beautiful argument" or occasionally the classic puzzle of the "argument from beauty". Where the continuity or the equanimity or the compression of the argument evidences its strength or its presence – much like beauty in mathematics. So the notion of beauty in an anchor poem like “Engram Sepals” is defined by its continuity and 'thoroughness'. As the collection argues both in favor of the unfinished argument, and has some envy for the arguments that 'take hold' ("I am not here to summarize that beautiful argument"), there is some thought on beauty as a durational coherence perhaps. I would need to consider it more.

The sublime is not a conceit (or term) I use much, though there is some readiness in me for surprise, rapture and joy. Joy is the apposite term that comes up most frequently in my writing, most recently as an aphorism that has repeated itself through a few verses: "Absent joy, poetic disability." Despite all of my metaphysical preoccupations, perhaps there's an inevitable utilitarian cast to the verse? In that sense, if the pleasures of the imagination are their own end, then I lean into the sublime more often than I may confess. I think there's some belief that a proper aphorism produces sublimity of a sort, but I often judge the success of an aphorism by whether it can capture and present a difficulty. Am I interested in 'sublime difficulty'? Maybe. An exotic substance, no doubt!”

Though “Engram Sepals” includes the line “Blackguard, don’t quote me,” I quote here a passage that might be seen to address, in a beautiful way, the dangerous place one can be led to in reading Candor. I think it might also suggest and why I have walked down this strange conceptual path in thinking about the text. Maxwell’s writing confides, offering complexity and inviting interpretation. As he himself has commented, “The keys in the book are at least partially permission for the reader to re-assemble or self-assemble the material outside the arbitrary confines of the book.”

To confide is not to repeat but to arrive

In a ruthless space without attribution

Oh “ruthless space” without attribution

Gain a groundless moron, leashed outloud

My uncompromised elegy, a canker or a blossom

I’ve looked for us there, to name itRadiant species, “an asterisk in thy region”

from “Engram Sepals,” “The Prior Art,” Candor Is the Brightest Shield

This might be a good time to point out that the epigraph to the entire book or collection of books is a series of asterisks. It surely would have been possible to discuss only that aspect of the text in these notes. The other epigraph is by Thomas Browne and includes a photo:

These pages appear early in Candor Is the Brightest Shield. In the book they both face blank pages, rather than each other.

There are a number of such emblematic qualities (and subjects) in the book. In fact, they are presented in the “KEYS,” preceding the sections, mentioned above, along with the dates of composition of that section. They include: “Version control. Invention. Prior art. Attribution. Quotation. Pseudo-folk. Inventory. Vernacular. Direct address. Paternity. Invention. The epigram. Pedagogy. Derivation. Authorship.Taxonomy. The visual intelligence. ‘Human interest’. Porosity. The bounded society. Models. Animal grief. Color. Paternity. Numeracy. Empathy.Consensus. Direct address. Exceptionalism. Ontology. Cowardice. Minority. ‘Dirty intelligence'. and The ecumene.”

It is tempting, even inevitable, to let A Maxwell explain himself (and I give into this temptation both above and below), however, it seems unlikely that, as any writer, he fully appreciates what is most compelling about his own work. For me it is something like an extreme, somewhat peculiar, intelligence coupled with a courtliness toward the reader that allows her to feel included in the writing as she does the work of appreciating and being persuaded by its many qualities.

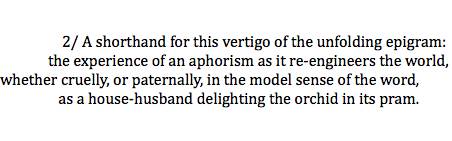

One auspicious quality is the presence of aphoristic, or, perhaps, epigrammatic lines containing incessant turns of phrase that seem to sum up, again, key aspects of the whole project. “Aphorism” serves as a theme as well as a form in the Maxwell’s oeuvre. From the epigraph to Peeping Mot:

Though the word “aphorism” doesn’t appear in Candor there are two sets of numbered statements, in “Life X” and “Ottolineal,” that have an aphoristic feel—or perhaps, again, they are epigrams. “The epigram” appears as one of the KEYS, as you will note above. These numbered lines seem to aspire more to truth than wit—although they are sometimes witty, they lack the weaponized aspect of the epigram (which you would expect in a writer whose DJ handle in his weekly KXLU radio show “The Dream of Harry Lime” is Papa Gentle).

7

Mischievous daughter—like the epigram, a portable form of life that demands allegiance but not taxonomy.

8

The optimist’s view of curiosity is that we like many things —

the pessimist’s that things in their nature mean to consume us.9

Reserve is the daughter of disinclination.

from “Ottolineal,” Candor Is the Brightest Shield

Another important aspect of Candor is that it comprises a series of short books composed over a decade and a half (as Maxwell explains in the helpful “Composition Notes” at the end of the book). These self-publications were written and printed to be part of a gift economy of poetic exchange, now finally, fortunately, captured into a form much more convenient for the sharing of art and ideas than the tiny chaps one gets, or not, from the author. Fifteen years is a long time and the density of thought and artfulness of the work attests to a changeable and inclusive writing practice that engages variously and profoundly with its subjects. Maxwell’s writing often defines, explains or proposes but it also sings, rants and apostrophizes until, catching itself, it again becomes definitional. Or, rather, it accomplishes all of these tasks at once in a way that is cunning and yet sincere.

When definition is this relentless it seems to unwrite itself.(Inappropriate aside: I just remembered I have been accused of this.) The reader wonders what the writer is doing that he is not telling or not aware of or hiding or failing to do. But, failure is included, even cultivated, in this work. Maxwell seeks clarity, the simple accurate statement, but never at the expense of negativity or contradiction which, when found, seems always to be a source of delight. At times, a line, word, or theme will contain its own counter-argument or tragic fall.

The Lifer

Occasionally scraps would escape

the flames and shoot out into the air, spinning.And I can’t live the quote.

Let’s forget how we* lived, for

we* lived as we do. This gay cloverand I won’t close the quote.

The scraps are ours*.

It’s the literature that’s inconsistent.

from “Quotation or Paternity,” Candor Is the Brightest Shield

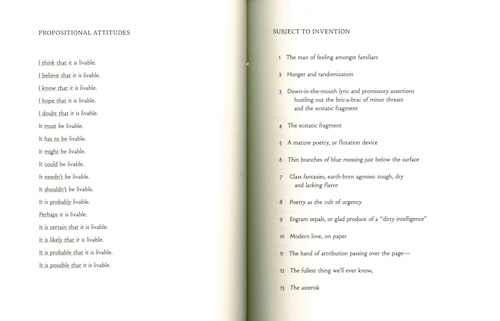

But let’s read a bit further, or actually back, in the same section. In the facing pages below, chosen almost at random, we have a series of propositions on the left and then a numbered series of what we are invited to regard as “subjects” on the right. With “Propositional Attitude,” much depends on what “it” is. Let’s say “it” is “life” or “writing,” or “this poem” or “book.” Or let’s say, instead, that “it” is “the situation” or that “it” changes in each line. There is a Steinian quality of repetition here where there is change but also sameness. The poem is succinct, an elegant container of carefully composed content, perfectly framed on its page. It is also sad. What if “it” is not “livable?” What if we are talking about one’s job, life, or the present time?

Moving to the right side of the page, “Subject to Invention” seems to offer us the permission to invent, change, improve or in some way mess with these subjects—a permission granted, to some degree, throughout Maxwell’s work, as mentioned above. Moving on, you might intuit, reading a line like, “A man of feeling among familiars,” that we will be reading a series of pieces about the daily life of A as he goes about his occupations and you would be right, sort of. Daily life is very much contained within the pages of Candor but it is the daily life of thought, distilled into phrases more thematic than descriptive—even, maybe especially, when they refer to something as visceral and daily as fatherhood. (See daughter-related aphorisms above.)

The numbering in “Subject to Invention” makes the poem a list (though it lacks the relentlessly parallel structure of the classic list poem—that “Propositional Attitude" demonstrates). And what is a list if not a reminder to oneself about something—how to write or live or read, or as, possibly in this case, what to look for in the book? A list might be a table of contents, allowing the reader to take the piece entirely as that, or as a list of issues or exercises. Sometimes, in thinking about my own life, I ask myself “What is true?” These lines could be read as answers to that question. “Subject to Invention” concludes with the lines

12 The fullest thing we’ll ever know,

13 The asterisk

Let us take this opportunity to begin the interview part of these notes, and allow A Maxwell to respond to my question to him about his use of the asterisk—as well as to my other queries about his poetics. What follows is pieced together from several email exchanges.

Moriarty: Is your sense of the asterisk about a desirable modesty in the face of history/eternity or like an atom or relational like a footnote or other? Or does it relate to identity?

Maxwell: The asterisk is obviously a very overloaded conceit in the collection—and it's meant to remain ambivalent. But the most important sense for me to explore is how the asterisk helps illustrate what is gained or lost in attribution and identification.

I don't write toward a book, toward a version, toward the fixed or indexable object. The tendency of my practice is toward anonymity, away from publication, provenance and authority control. The asterisk captures this very economically, as it began as a printer's mark to identify date of birth, especially in family trees—basically a mark of provenance. Now it's used chiefly to qualify language—either for emphasis, or contrastingly, to trouble the original sense, to point away from its original emphasis, even to the point of becoming a strikethrough or elision or the text. From identity to something nearly opposite. And when it stands apart from language, it is often a wildcard, almost non-relational, an independent variable. The title of the first section paraphrases this aspect of the asterisk: quotation or paternity. Is the language owned or borrowed, and can we conceive otherwise, of a "groundless space without attribution" apart from the ownership society of Literature? There's this copyleft emphasis on moving from a Literature of authority control, with carefully policed brands and names, to "the literature" (as we would speak of in law or science)—a peer-constructed body of knowledge built on propositions, concerns, arguments, ideas. What if the ideas were the vernacular, and not the other way round?

So there's a bit of sorcery in the asterisk, in that captures both identity and provenance, and troubles it as well. A vague mark (like a star) that become blinding on closer approach.

The italic is similarly important. "Life is the italic (what a shame!)" The notion that we can only say, or address, through a stress in a text which is never ours. If you notice, the font I chose for the text is almost itself an italic, and this is by design. Because all language is owned, because Literature inclines so much toward invention and innovation, it takes an extraordinary amount of stress to address another, or to speak to an idea, through the language.

Moriarty: With regard to “candor being the brightest shield,” from what is one shielded?

Maxwell: Identity, yes. It ambivalently references direct address, and the fixed identity that a speech act demands, both from the speaker and the imagined audience. Direct address is an act of identity formation and projection, and troubling because of that. The language of Candor is anxious about the petrifying power of verse or speech, which is why it often mentions "music or internment," or being "locked in a music."

Two conceits this references are the shield of Perseus, used to prevent being petrified while killing the Medusa; and Barbara Guest's concept of "defensive rapture." I don't know precisely what Barbara intended to mean by the title, but I can imagine it. A sort of radical ekstasis that allows one to preserve a life unreduced by all what conquering authority, ultimately by standing apart from oneself.

Again, there's a radical ambivalence: direct address is what I most want, but cannot have without submitting to the coarsest version control.

Then, the fight to "live the quotation" as opposed to merely pointing to it, as a tourist might.

Moriarty: As I was reading I imagined a thought tree (not unlike a phone tree in terms of relationality) but realized it was insufficiently complex. In both Candor and Peeping Mot I see a kind of lyric discursivity, explanation vexed by puns or false (or slanted) explanation.

Maxwell: I'm certainly interest in discursivity, and the progress of my work has moved on from verse, which I'm not terribly interested in, toward forensics. I used to think I was trying to evolve a didactic verse (in the spirit of Philippe Beck: une poésie didactique), but it's become more of a forensic verse. Poetry is useful to me as a free field of argument, where its propositions are tested in a very "undisciplined" way.

The main test is whether or not the propositions of poetry are livable. What are the implications of me saying this? So when I do write a poem, it's usually begun with a difficult proposition that I do not fully understand, and the resulting argument intends to demonstrate the consequences of living out that proposition. And over time, I've tended to write more propositions, and fewer poems, because a fair amount of my life is spent in suspense and bafflement.

When I began paying attention to what my contemporaries were writing in, say, the 90s—the post-language and post-lyric period—there was so much ellipsis, so much anxiety over subject position and declaration, and a tendency toward a very ambient poetry that avoids any sort of statement. I wanted the opposite.

I wanted to see a poetry full of propositions and arguments. And a recognition that all these "arguments of the past" are essentially unfinished. Not in the sense of the gardening, of hermeneutics or scholarship, but in the real sense of lived debate. The world is replete, and also unfinished. Every argument in the archive is still very much alive.

These are just a beginning. There are some questions of representation I have not quite formulated but one might simply be "How, why and what one does one (do you) represent?"

The easiest response is that I am not one.

There's a mutating pun in the book: "I am not one to be free of it" or "I am not of the kind to be free of it." Which is reinforced by the line: "Self-possession is one of the stupider accomplishments." Again: a resistance to the categorical, or the impulse to taxonomize the self, to submit to version control. Even at the risk of disappearing, and leaving all the texts unmarked.

Revealing a radical secular pluralism that is skeptical too of most humanisms. (Which is why the collection also focuses often on animal intelligence, and human-animal interaction.)

There's the voice of the book, of course, which I keep joking is that of a 19th c constructivist. There's no question that the speaker has no interest in speaking to his or her "time." It's interesting that we take it as a given that there are multiple parallel universes that we live within, but less so that there are multiple times, which is merely self-evident given an archive that is virtually always accessible now.

In some ways this rehearses Spicer's second letter to Lorca (ie, poet as "time mechanic"). But I'm always surprised at how uncomfortable contemporary poets are with speaking to the elders, or to writers of other times. And always, always the preoccupation with capturing the vernacular of "our time"—that reductive consensus—to speak to our contemporaries.

I'm not one / to be free of it.

Moriarty: I have a long interest in allegory as a fallen form and am curious if you have an opinion of it? The word comes up a number of times in Candor.

Maxwell: I'm drawn to paradoxes, and taken by the arguments available through allegory, and since so much of my work is involved with value arbitration, allegory is seductive.

But I'm also skeptical of metaphor, and obsessed with the problem of universals—of nominalism and particularism. While I find it almost impossible to write this way, I think the world is composed almost entirely of discrete detail, and endless variation, which most generalizing devices occult or destroy. So I'm suspicious of allegory, even as I'm seduced by it. (Like Marianne Moore was seduced by La Fontaine.)

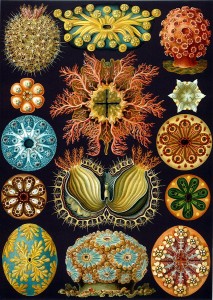

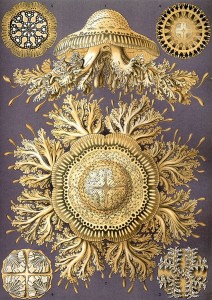

In spite of the length of these notes and A Maxwell’s comments, I feel I have only just begun thinking through the possibilities that radiate outward from his work in a wild but controlled way, not unlike the radiolaria exquisitely and familiarly presented by Ernst Haeckels in his 1862 monograph. Turning to Haeckels also allows me to end with “the voice” or images anyway “of a 19th c constuctivist” (and taxonomist.) It can perhaps be said of much of the best poetry that one both observes the poet thinking and thinks along with them, the elements of their minds entering one’s own like Burroughsian viruses, changing everything. Reading Candor Is the Brightest Shield and Peeping Mot is to be invaded by an especially effective and pleasurable version of these ancient and yet alive beings. The images below are not part of either book, except in the inner life of my reading them

Born in St. Paul, Minnesota, poet and novelist Laura Moriarty grew up in Cape Cod and northern California...

Read Full Biography