Graffiti is always already camera ready—always was. “We decided to take the train to Baychester station,” Lee of the Fabulous Five told Craig Castleman, in a long interview that begins Getting Up: Subway Graffiti in New York (1982), “and when the train stopped we’d pull the emergency cord to stop the train. That’s our specialty. So when the train pulled in, BOOM, we pulled it and I took some photographs.” Lee was describing the whole train—ten cars on the IRT #4—that he and his crew covered top to bottom, two weeks before Christmas, 1979. They called it the “Merry Christmas to New York” train. A razzle-dazzle of rainbow hues, with Mickey Mouse right in the center and Santa Claus and a snowman and snow, reindeer and trees at the end, “Every car was like a TV,” Lee said, even as the windows in the slums reflected the colors from these passing cars. He claimed the reciprocal spectacle was a “big show stopper and I think those people who saw it went home that night and didn’t watch TV. They talked about the train they saw.” If the photographs of that train by Henry Chalfant—and of many others like it, by Martha Cooper, Lynda Forsdale, Gabrielle Oldham, Ted Pearlman, and Yolanda Rodriguez—are legendary, they’re also just the extant record, for the taggers had been collecting images of their handiwork all along. When the Christmas train pulled into Intervale in the Bronx, Lee “was going so crazy I forgot to take pictures,” although the preceding nights’ strategic maneuvers had involved carting his camera everywhere, to document the work. At Baychester, after yanking the alarm, he and the rest of Fab Five—Mono, Doc, Slug, and Slave—jumped out onto the rocks to take snaps. “And everybody’s there with their 35s, clicking,” he recalled. “It was a nice sunny day. And when the train left, we said, ‘Yeah, all right. Job well done!’”

Off la rue Dénoyez in Belleville, there’s a passage between two bar-cafés, the Bar au Vieux Saumur and Aux Folies, where spraypainting is permitted, while clients sit and sip their drinks. The alley knows people will want to shoot it—the place is posed from the get-go for a photo. At the entrance, you cross a placard in memory of Lounes Matoub (1956-1998) Lwennes—who seems, himself, to be looking at himself. In fact, “Chouf !” turns out to mean “Look!” (I’d thought it might have said “Chout!,” i.e. “Shoot!”) The brickwork is such that a classical “rule of thirds,” albeit slightly askew given my position below the subject, is inscribed in this photograph. So someone can be reasonably assured that her pic will conform to the norm.

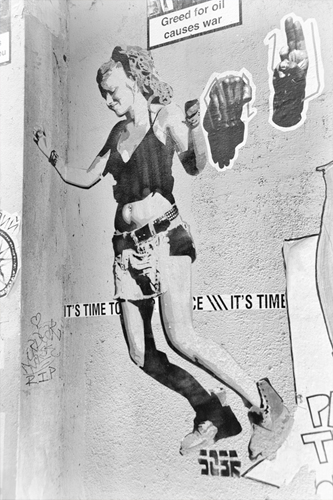

Two summers later, I found myself there again. With twenty other troopers, roughly our age or a little younger, my wife and I were finishing a Street Art Tour. Though our guide was French, the tour was in English, and I later found it enthusiastically written up at something called (I can barely bring myself to say it) The Hip Paris Blog. So it made sense we’d wind things down by running a tourist gauntlet of the official interstitial, on a street whose name practically broadcasts the lighter side of l’art. The verb noyer means to drown, cover, or hide, so Dénoyez Street would be the avenue of unveiling. A noyer is also a walnut tree, so I likewise think of dénoyauter: to remove the pit from a fruit. Sweat out the grit and leave the sweet. (In fact, the street takes its name from the Denoyez, a nearby tavern in the 1830s.) Despite the moniker of the sponsoring group, Underground Paris, none of the trek took place below the sidewalk. Moreover, most of the artists whose work we encountered—BMX, Nemo, Paddy, Fred Le Chevalier, the late Zoo Project—are apparently tolerated by the mayor’s offices of the 11th and 20th, who presumably reap the benefits accruing from the international reach of a few of these folks. Among the more interesting is Sebr, whose disco or go-go or rollerblading girls, plugged into invisible ear buds and poised to float free of the walls, join designs by Miss.Tic, Sara Conti, Madame Moustache, and other female artists in offering imaginative, necessary, often socially conscious antidotes to a still overwhelmingly male street art scene, if not to the discourse around it. (Of the thirty-five artists or collectives profiled in Paris: De la rue à la galerie (2013), edited by Nicolas Chenus and Samantha Longhi, only two are women—and one forms half a duo, Jana & Js, whose stencils sometimes feature people brandishing cameras, even shooting the viewer. The other female artist included, YZ (pronounced "eyes"), has recently been putting portraits of women, famous and anonymous alike, up in Senegal, a former French colony. Her project, “Amazone,” pays tribute to the group of Fon female warriors who fought against the French, and lost, in 1890.)

Still others from the hood: Portuguese sculptor Alexandre Farto, a.k.a. Vhils, chisels large-scale faces into limestone facades—a sort of Rushmore in reverse—, while CONIE is another exemplar of backwardness: trained at L’École des Beaux Arts, he began a career as a fine-art painter, before thrusting block letters onto walls with a pair of refurbed fire-extinguishers, like an urban gunslinger toting two revolvers, one in each hand. Some of these artists are encouraged, even supported: Jérôme Mesnager, for example, among the founders of the Zig-Zag group in ’82, was commissioned by the city in 1995 for the enormous tableau of people dancing that dominates a tower on la rue de Ménilmontant. Around halfway we stopped at a street art sale on la rue Piat, with a splendid view of the city. Now in its fourth year, the “Irrueption : L’Expressif Belleville Festival” has recuperated the disused Parc de Belleville and opened the space to the public. Wandering these hilly environs with an eye on the many decorated walls, I had the feeling that Ménilmontant was being fabricated and carefully exported as the new Montmartre, an easily romanticized moment, or movement, likewise up a mountain—the geophysical opposite of underground—and also branded “alternative” during its era. You could make a movie about it; they never stop making such movies. This film could be called “The Children of Marx and Coca-Cola.”

Andrew Zawacki is the author of five books of poetry: Unsun : f/11 (2019), Videotape (2013), Petals ...

Read Full Biography