Portland, Oregon

Today is the one-month anniversary of my friends Avik Maitra and Patrick Worth, who got married in Portland. When I got married—six years ago, in the Cambridge, Mass., City Hall—I was two months pregnant and understood this was a moment my family would never share with me. But Avik came and stood next to me in their stead. We’re born with families, and we make them. Even the ones we’re born with, we have to learn to be part of and to maintain. Neither a wedding ceremony, nor a signed and state-sanctioned piece of paper, are necessities for this, but I know for a fact that it can make a difference—to know, or not to know, whether all your families and the institutions you value and bring to the table are willing and vowing to be in this together.

Avik, a designer, and Patrick, a doctor, asked me to write something for their wedding. Asking your poet-friend to write something for your ceremony seems logical enough, but in reality it’s both an act of faith and an act of foolishness. Asking your experimental poet-friend who was disowned by her family and had, technically, a shotgun wedding to write something for your ceremony… you only do that because you’ve made your poet-friend part of your family, because like it or not, you have to let your faith in her exceed your fear of her foolishness.

Here is the text I read for Avik and Patrick’s wedding. Because I’m a little perverse, I decided to talk about Marianne Moore and to make it dark and academic. But I’m not perverse enough to ignore the context. It is my way of saying to Avik and Patrick, “No matter what, I’m in this with you.” Thank you for letting me be.

***

Do you read the “Modern Love” column in the New York Times? When we lived in America and had a paper Times subscription, I read it religiously. “Modern Love,” “Vows,” Times Magazine, the Book Review and then, finally, a quick skim of the front page, all while drinking coffee on our shabby yellow couch and ignoring my children and husband. This was my Sunday devotional practice. Recently a “Modern Love” column caught my eye via Facebook; it was called “The Wedding Toast I’ll Never Give,” so I promptly sent it to Avik and Patrick.

Here, Ada Calhoun writes on the unspoken “and yet” of marriage vows. As she puts it:

I sit at these weddings listening to our in-thrall friends describe all the ways in which they will excel at being married... I clap along with everyone else; I love weddings. Still, there is so much I want to say... I want to say that at various points in your marriage, may it last forever, you will look at this person and feel only rage. You will gaze at this man you once adored and think, “It sure would be nice to have this whole place to myself.”

One of the hidden cultural functions of weddings might be to give already-married couples an excuse to act like this isn’t true—at least for a day. You can think of it as an inadvertent ethics: you get married to keep your friends and family married. For a day we all pretend, and tell ourselves, the wedding is the happily ever after. The End. In literature class we were taught, and now I’ve taught, that tragedies end in death and comedies end in a wedding. But the hard fact is, everything in life, tragic or comic, eventually ends in death. The fact is, marriage is never “The End.” It is the “And Yet.”

And yet. Here is an anecdote. In Marianne Moore’s poem “Silence,” from 1924, Moore observes, “Superior people never make long visits, / or have to be shown... the glass flowers at Harvard.” I am convinced that as far as superior people go, Avik and Patrick are the best among them. And yet, once, when Avik was studying design at Columbia and came to visit me in Cambridge, I took him to see the glass flowers at the Harvard Museum of Natural History.

The glass flowers were made by Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka, a Bohemian father and son team, between 1887 to 1936. Commissioned by Harvard as a botany teaching aid, they consist of 847 life-size models of 780 varieties of plants, and 3000 models of plant details, such as anatomical cross-sections and enlargements, all rendered through glass and paint.

Sure, these turn-of the-century flower models send my inner bourgeois lady-heart into a flurry, but I was worried Avik would find the glass flowers a little boring; even I, despite seeing him through his velour shirt and bowl haircut and J. Crew catalogue phases, still thought of him as an evangelist of the cutting edge, the contemporary, the unorthodox. The glass flowers seemed so old-fashioned, decadent, technical. I thought he might find them interesting and pleasant enough, but I wasn’t prepared for how truly overwhelmed he became, how extraordinarily emotional. “How could you do this to me?” he cried. “How can I ever make anything that equals this?” And periodically for the rest of the day, whenever there was a quiet lull, suddenly he would erupt: “How could you do this me?!”

The glass flowers are, without a doubt, an exceptional achievement in mimesis. It’s not just that you see the models sitting in the glass cases and can get the gist of the plants’ identifying features. No, the glass flowers continue to survive, to be studied, to be a requisite for “superior people,” because they are an extraordinary representation of the artistic will, the ingenious human capacity to transform. How to make something as sharp and hard as glass and make it look as pliable and soft as a daisy? How to convincingly depict the natural, organic curling of a grape tendril produced by the soil, sun and air through the meticulous, deliberate and determined shaping done by pliers, a hammer and a torch?

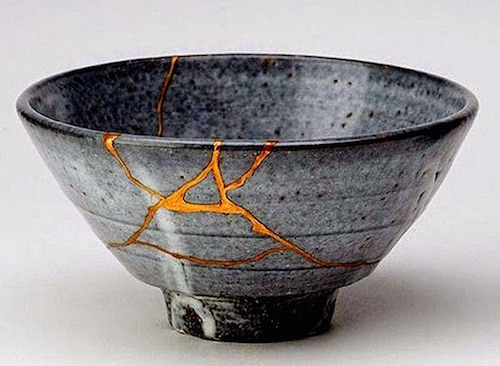

Seen through their glass display cases, the glass flowers are perfect copies of the original flowers, so perfect that they actually can be a little boring—Oh, it’s a daisy. It’s a grape leaf. It’s a marigold. It’s a lily. But sometimes you can see the places that the glass has cracked, or the sheen of the glue holding split pieces together, and these moments, when their age, their wear, their specific kind of fragility are evident, are when you see most clearly what a remarkable achievement they are. It’s akin to the Japanese art of kintsugi, where broken pottery pieces are rejoined using a gold lacquer—because the object’s history of breakage and repair is essential to what it is, and its beauty. These cracks represent the object’s “And Yet”: its openness to a future, its determination to continue, its acceptance of whatever happens into its definition, to acknowledge the breakage but still insist on the coherence. And all the yet’s.

Before I got married, one of my favorite love poems was Margaret Atwood’s “Variations on the Word Sleep,” where she writes:

I would like to be the air

that inhabits you for a moment

only. I would like to be that unnoticed

& that necessary.

It’s an exquisite and (literally) breathtaking desire—to want to be so essential to someone else, to be so integrated into them, that one goes unnoticed. And yet, even Atwood acknowledges this can only work “for a moment only.” Being married is, by definition, the opposite of “for a moment only.” Being married, I’ve learned, means that you can never not notice each other. Being married means having this individual and separate presence always next to you, always part of your decision-making, always using your towel before you take a shower, always wanting to go to a cold medieval church instead of a tropical beach for vacation, always saying things like, “I know Hillary is a good candidate. And yet, I do think she could be more leftist like Bernie Sanders...”

And so now I find myself turning back to Moore, who in addition to extolling the glass flowers in “Silence,” wrote a poem called, “Marriage”—a poem famously described as “an anthology of transit” and a “crazy quilt.” Here, Moore’s account of love’s union is far different from Atwood’s. In the poem, Eve says, in a “stipulating quiet” to Adam:

“I should like to be alone;”

to which the visitor replies:

“I should like to be alone;

why not be alone together?”

There’s a lot to question about this poem, but there’s also really something to consider. This is marriage not as the conflation of two people, or the consumption of one by the other (“I’d like to be the air that you breathe”), but as a co-existence; of sometimes wanting to be alone, but finding someone with whom you can be alone and yet together.

As Calhoun writes in “Modern Love,” “I love weddings. Still, there is so much I want to say.” And this is what I so much want to say to Avik and Patrick: That as much as you are promising today to create a life together, to be joined together, that hard fact is that you still will have your own struggles, your private moments of trouble, anxiety and insecurity. Because it is the inevitable “And Yet” of marriage, that after this beautiful and perfect day with everyone you love around you, and promising a beautiful and perfect life with the one you love most, tomorrow you will go on to face the world, and yet, just as you did before, sometimes you feel its full weight upon you.

You will look across the table, or next to you in bed, at the one you love most, and yet sometimes, inevitably, that face will add to your burden. You might feel like you’ve been sewn together in a “crazy quilt.” You will think, “The world. The world and you.”

And yet:

You might remember that marriage is, in fact, a “crazy quilt,” an “anthology of transit.” You will look across the table, or next to you in bed, just as you now look across the aisle, at the one you love most, and always, always that face will be there. But sometimes, sometimes, you will see behind the “and,” the “yet”: “The world, the world and you / The world, the world yet you.”

Marriage is this promise: that with you together, the opposites “and” and “yet” can call forth each other, can be among the possibilities of each other. Marriage, too, represents the ingenious human capacity to transform. And it is this ambivalence, like the glued cracks in the glass flowers, that grows and yet perseveres intact, that reveals what was once beautiful and perfect. And that then casts itself as what is beautiful and perfect.

September 26, 2015

Mia You was born in Seoul, South Korea, grew up in Northern California, and now lives in Utrecht, The...

Read Full Biography