What Undiscovered Countries Are Then Disclosed

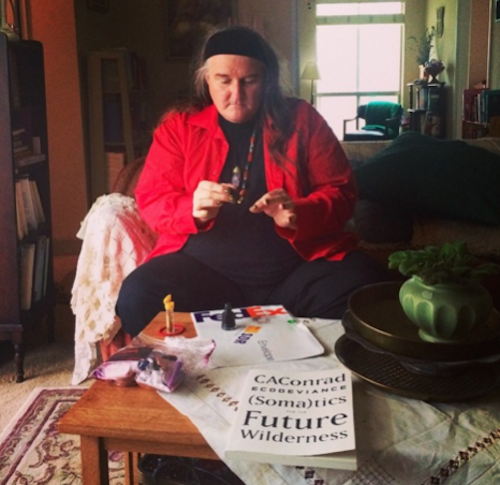

The nurses wouldn’t treat the pain. I had no one to drive me home, and it hurt—wickedly—the needle, the insertion of the titanium tumor markers, the size of tumor they were announcing. A few hours later, CAConrad came to town, gave me a feather to put in my bra, reiki-ed me on my dirty pink sofa, gave me crystals. He said he’d put his hand in his bag, and one of the crystals said to his hand “give me to Anne.” Stones could talk to him, and we drank miso soup together. Juliana Spahr texted what everyone else was probably thinking, too, “I’m glad that Conrad is there.”

The night I learned I had cancer, I dreamed my friend Jace Clayton and I were children on a raft in an endless sea. We were supposed to be on a radio show in a movie about John Wieners, but I could no longer think of any words. Language was a mess. Michael Brown was murdered by the police the day after my diagnosis. The world was a mess, as always—and I remember telling a friend I couldn’t join him on the streets, me such a mess, too. Ferguson, though a few hours away from me, could well have been at a distance of years. My feeling of political helplessness was a mess. And my apartment was a mess, the kind with vertical blinds on the sliding doors and furniture from the dumpster. Everyone visiting had to sleep on a sofa in what was supposed to kind of be the dining room half of a living room, or sometimes on an air mattress with holes in it, one that would deflate each night.

My friend Louis-Georges came for the first chemo, leaving behind his anarchist poodles to take care of me. His father had basically been one of the inventors of chemotherapy, and LG helped me with the condescension of the oncologist we’d all taken to calling “Dr. Baby.” That doctor looked like a cherub and acted like I was crazy. Each time I showed up for an appointment, he could never understand my people, none of whom was family or of any expected relation in a place where the chemotherapy infusion room was limited to “one family member at a time.”

I was alone at the surgery to put in the chemo port—a plastic device installed into the chest, connected to the jugular vein. That’s the place the infusion needle would go and with it the substances they would infuse into me—these substances so poisonous that they would otherwise burn flesh and corrode veins, that would, if they were spilled on the floor, eat a hole through it. I wasn’t supposed to be alone after that surgery, but I didn’t know what that meant or why no one told me beforehand—wouldn’t they have said to have people around before they gave me anesthesia if it had been important?

Audre Lorde began her Cancer Journals in 1978 with: “I want to write about the pain.” I want to write about the pain, but instead I woke up in terror with it, inarticulate. That night Cara drove across town to drive me to the ER, stayed with me as long as she could, but had to go to work, so I spent hours alone in a room there—forgotten by the staff, no pain control, dehydrating, sending upsetting texts to my friends until the phone died, unable to move myself out of the bed, except very slowly and with a lot of pain, which I finally did, and dressed myself, would have taken out my own IV, too, walked to the hallway and said “This place is horrible. I’m leaving.” The doctor, feeling sheepish they’d forgotten me, gave me so much morphine for the road, then a work colleague, Jonah, drove me home. This—all of this, but particularly the suffering of considerably more pain and fear than necessary—is what happens to a person who is sick alone.

Cancer is an industrially-transmitted disease. The kind of cancer I had—a non-hormonal breast cancer in a young-ish woman—was historically specific to the 21st century carcinogenosphere. The world had made me ill, then it made serious illness impossible—not enough money, not enough leave from work, not enough care. My friends—many of them poets—had to patchwork a form in which to care for me in a world in which single mothers who work for a living did not fit into the scheme of care, except as the people who provided it.

“Promise when I am ill, you will take me out back and shoot me,” a person at work said. Many people said, “I would rather die than …”—the ellipsis to be filled in by whatever it was I was going through, their frequent and absent-minded reminder that so many people would rather be dead than be me. There is a respectability politics to cancer, too, the blatant calculations of what you must have done to have fallen ill with it—did you eat your kale? exercise? stress manage? The other blatant calculation, the one no one even felt ashamed of performing, was that of whether or not I was cheerful or strong enough to survive my illness, as if cancer actually cares about personality. The disease, I assured the speculators, wasn’t interested in the particularities of my character.

I was on the phone to Dana Ward so much in those early days, full of fear and complaint. Under the existing logic of the world, reproductive labor (the Marxist term for what it takes to keep alive ourselves and others) was mostly unwaged, often invisible, unrecognized. Care was mostly to take place unwaged inside the structure of the family or through the poorly waged work of women. The distribution of care—just like the distribution of cancer—was often gendered and racialized, part of a larger history of what is kept mostly invisible, mostly outside of politics. Care was work that was supposed to be paid with (that brutal abstraction) love. When sick, I read that Maggie Nelson book, The Argonauts, in which a single woman with breast cancer—Nelson’s partner’s mother—is removed from the nuclear family’s home because there was not enough space in it for her to die. Breast cancer is the disease of the minor character. And hadn’t this kind of expulsion of sick women without a partner, hadn’t this been exactly the political condition that I had spent so much time worrying about with Dana and in the poetry we would share with each other, this condition of who is always supposed to give care, but never supposed to receive it?

Poet and essayist Anne Boyer was born and raised in Kansas. She earned a BA from Kansas State University...

Read Full Biography