Jimmy: What I Learned From My Father About the Criminalization of Black Griot Culture and the Poetics of Rehabilitation

I was so young when it happened that I did not really allow myself to unite the two hemispheres of meaning until this year, as the cavalcade of black men and women dying in prison is becoming more apparent to the mainstream, it dawned on me that the police officers taking my father away to jail the last time I laid eyes on him in this realm meant that he died in that cage, and spent his final weeks living in it. I was so young that I couldn’t imagine past the threshold, where I remember peering through a crevice in the door as they drove him away in chains, waving like this was a carousel at some carnival or fair or carnal barricade to stare into and through. And I was a ruthless accomplice. I was never afraid of my father, but my mother’s life was in danger—I knew that. Every once in awhile I would watch him pull one of his many guns out of his suitcase and threaten her with the barrel to her head, or choke her, or suddenly I’d look up from a coloring book and she’d be tumbling down a staircase. This became casual. But now she was nine-months pregnant with a broken jaw, living on liquids and baby food while it healed. My father wanted to take me and run away from what he knew was coming, and every time my mother threatened to leave the violence would escalate.

I scrutinized his every move with a child’s unmatched, brooding secrecy. I knew that he took long afternoon naps with the phone off the hook and right by his head—that was when we used stationary phones attached to the wall and anyone who called would get that obnoxious old-school busy signal; if we picked up and tried calling anyone, much less calling for help, he would wake up and draw a gun on my mother. So this snowwhite winter Iowa afternoon it was a near miracle that my mom had managed to call the police during his ritual nap, unprecedented that dad had slept through it, that when the men in uniforms arrived at the door and my mom told me to go up and wake him and say it was his brother who had stopped by to see us, it was as if staged that I marched upstairs to their Clockwork Orange-esque circular bed, nudged his shoulder, dad, Uncle Percy’s at the door, and he woke in a cheerful mood, grabbed my hand and headed down to greet him. I’ll never forget the agape, petrified stillness of his eyes when he saw the two white cops standing there, and how, though I was too young to fully comprehend, I felt I had betrayed something organic and just in the power structure. I wanted to slam the door and say never mind, but I also wanted us all to survive. If you leave me I’ll die, he pled quietly, the last words I remember him saying, though those were not his last words at all.

A mugshot, fingerprints, strip-search, maybe a light clubbing and some degrading words, before the cage door of blind fate slammed shut. It can’t be overlooked that my father was bipolar and that when he married my mother, aware of his talents as a songwriter, she suggested he go off his dosing of lithium, and he complied. My father was a famous songwriter and singer who lived for his craft, the drugs made him safe but also apathetic. He had used his talent to escape life as a sharecropper in the Mississippi Delta and found his way to Hollywood where he worked alongside Ray Charles and Bobby Womack. He was back in Iowa after divorcing his first wife, because life in Hollywood had served to drive him all but mad. He bought his mother a house across from ours, and his brother Percy lived a couple doors down. Had it not been for the violence, ours might have been deemed an utopian family scene. My cousin Liza and I would play outside everyday for hours, my grandmother would fix my hair and cook perfect greens, my mom and I had fun doing crafts while my father played the piano and composed new music. We would take long winter walks, the three of us, and arrive at the small black church where I watched my whole family, cousins, aunts, uncles, dad, sing and testify, and I would have never guessed the kind of trouble that unfolded as our beauty.

And then every once in awhile my dad would pile us in the car to drive cross country during a manic phase, or sleep or sit on our sofa in catatonia when disillusioned. I am not saying any of this makes my father a victim, but I’m certain that he was a born poet and where on his journey from the Delta to Hollywood, to rural Iowa, had he learned to turn on himself in these ways, how were his external conditions as a black man in Jim Crow U.S.A. related to his internal struggle, which ultimately overrode all of his harrowing accomplishments in his own mind, and took his body away from this place. How did his time in jail in those final weeks of his life impact his spirit, in relation to the rest of his life, and in relation to additional black artists who are placed behind bars for both violent and nonviolent crimes, from Etheridge Knight to Tupac to Malcolm, and MLK. It is my belief that in order to survive as a black male artist in the era during which my father was most active, you had to be Machiavelli, you had to be feared as well as loved, destructive as well as creative. The tools developed to sustain a professional life under these conditions are actually intended to preclude a stable personal life. The dignity sacrificed to be seen and heard in pop culture context was recouped in private as how-you-like-me-now attitudes in the home, postures that could not be taken by black men publicly, like exhibiting any semblance of true self-confidence, turned into lashing out in domestic spaces or dope habits to satisfy the urge to go over the ledge. A mixture of a decimated self-image, disembodied and then reembodied with the vapid cult of celebrity, overcompensating machismo, and a deep inner faith and sensitivity that marks the souls of all true black artists, made life away from the stage decadent and totally disjointed. Mates could not understand this if they tried and all efforts to comfort the jagged edges away grew trite or empty, only peers could commiserate and so they gathered together and destroyed themselves little by little, in order to create.

--

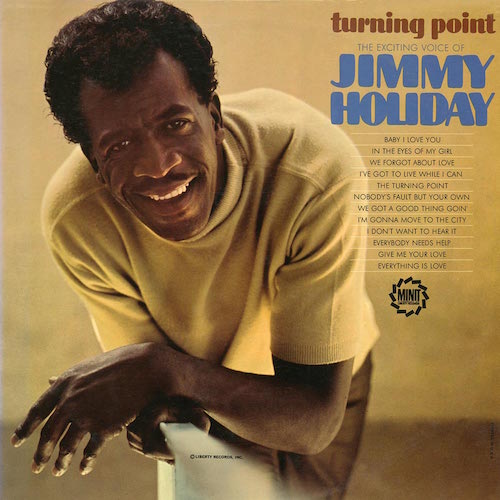

Economically, there isn’t much of a difference between sharecropping and slavery. Black families like my father’s lived in shanties on plantation land and tended cotton and other crops, and ‘sold’ the harvested crop to the landlords at a rate that afforded them lodging and covered the most basic needs. There was a quotient of emotional freedom that chattel slavery had not offered, but blacks were still bound to another man’s dream, still black bodies were creating white wealth which means still black bodies were and are the wealth of this nation. If the season yielded a sparse crop or if on a whim the owner of the plantation decided to lower the price of a crop, debt accrued, fueling a cycle that made it feel impossible for sharecropping families to get ahead. In my father’s case this meant he was a field hand along with his seven brothers and sisters. He went to grade school here and there but the duties of the land overrode any educational needs by the time he was twelve and even during the years he spent in school, books were hard to come by—school was a series of oral history lessons. So there was always music. He would use scraps of rough bark to build two-string guitars, and in church there was no economic injustice that could enslave the black spirit in my father’s town. Even as they used the bastardized doctrine of a religion tailored to serve colonialism, there was something more ancient at work in black hearts as scripture became song. And it was that fertile, invisible power source that gave my father the courage to leave his town for New Orleans as soon as the train started running along that route. With no formal education and hardly able to read his own name and heart full of song, my father set out to be a singer and songwriter. He was signed early on, this was the era of work-for-hire contracts, shoddy agreements that turned artists into a new breed of sharecroppers, trading the rights to their music in perpetuity for studio time. Jimmy made a series of 45s for Everest and Minit Records in New Orleans before trying his hand in Chicago and then ultimately in Los Angeles where he went straight from the train to Ray Charles’s office at Tangerine Records and sat there day after day, all day, for a whole week, with demo in hand until finally Ray instructed his stoic secretary, let that nigga in.

Jimmy’s days of work-for-hire bondage were over. He and Ray Charles became fast friends and my father’s recording career advanced at a meteoric pace. This was around 1960 and he would spend almost twenty years in Hollywood composing his most well-known work for both himself and other artists as well as doing A&R for major labels. And how did he manage to be a songwriter when he could not really write his songs down on paper? He married a woman who would spend hours up at night with him writing the words he dictated and reading them back while he worked out melodies at the piano.

Psychologically, all of this hustling to be essentially a properly compensated griot poet took its toll. Living in all-white neighborhoods after his childhood in the Delta took its toll. Jimmy mastered martial arts and started collecting cars and guns. He mastered megalomania and he mastered tenderheartedness and he mastered the art of making everyone with whom he crossed paths both love and fear him. He was known for playing chicken with a loaded gun with anyone who tried to swindle him, and for karate chopping recording engineers for trying to slip out of sessions early. He made my sister hold the wooden blocks he broke in half with his hand and trained her to never flinch. Imagine having a family to feed with this immense talent and not being able to read the contracts white men offer for your work, always in search of the hidden wink from these men who resemble the landlords that exploited your whole family in the Delta. It was safer to be feared than to be loved and the bravery of his position as someone who took no shit from anyone inspired both, along with the respect of his peers. He also shepherded his peers. My mom recounts a story of him at a party at Sly Stone’s house; he walked in and saw a group of his friends leaning over a table covered in thousands of dollars of cocaine, about to snort, and Jimmy knocked it all onto the carpet, quipping I’m sick of seeing my people do this shit. I inherited that sense of disgust with weak wills from him. He could have been killed, but a man willing do that clearly didn’t fear for his life in the traditional sense—he was out to guard his spirit. Alter egos allow that. Myth gives the spirit room to breathe, even if you have to perform the myths with your body in order for them to exist. If you’re not a myth, whose reality are you?

It went on like this until one day the myth became too real, it commingled with his sense of duty and underlying sense of despair and Jimmy began patrolling his Beverly Hills block shirtless with machine guns strapped to his chest, knocking on the doors of his ‘well-to-do’ Jewish neighbors talkin’ bout he was the neighborhood watch there to protect and serve them. This was displaced solidarity with the Black Panthers and the growing Black Power movement, enacted in a sterile suburban environment. Needless to say his neighbors called the police and he was taken to a facility where he was given drugs and electroshock therapy and prescribed a now illegal medication that was often tested on black patients at the time, called Thorazine, which gave him seizures and strange visions. Eventually, after years of depleting his body with that he was switched to lithium, but none of it resonated or fixed the core dilemma and Jimmy was wise enough to reprise the southern Baptist myth in the Midwest and move to Iowa to be near his mother and brother, to start a new life.

---

When Africans were abducted and brought here it was not just the sheer horror of that act and the system that ensued that made it so devastating. There is a reason certain bodies thrive in certain lands. We are a tropical people and require minerals that thrive in tropical soil and more minerals in general. And more sun. And more sunrays need to hit the soil to give the plants we eat enough light energy to be mineral-rich enough to sustain us in our optimal states. To keep our souls in our bodies and in charge of them. Specifically, overlooked trace mineral like lithium, copper, zinc, and selenium, which are missing from U.S. soil. Elements naturally present in West African soil and not all present here. My father was 6’3’’ and mahogany black which means he needed more selenium and lithium than most, copper to conduct them, zinc to regulate his endocrine system. Without these minerals in proper supply, which means coming in daily, our brains begin to turn on themselves and so it’s no mystery why lithium would help his condition but also sedate him, too much of one, and other minerals are kicked out and imbalances accumulate for a lifetime with little reprieve, and with imbalance comes delusion, hormonal imbalance, adrenal fatigue, a mire of symptoms that Western diets have no business dealing with, and cannot begin to overcome. So the man who emerged from that mire, the myth who did, had so much stacked against him that a kid from the Delta with dreams of being poet and piper was made into part-time monster.

His spirit was still in there though and when he got to jail it began bursting forth in soliloquy and song. The guards didn’t know whether to become his audience or discipline him, and he composed behind bars a kind of closure, a series of redemption songs that he would sing to me and my mother over the phone when we called to check on him. Having no one to write them down for him, he went back to relying on his memory, which took him back to the tribe in West Africa, which he was sure he was from, one with a clicking drum-like language that he explained to my mother in detail, how he had been a king and would be again. How we were his crowns and must wear ourselves as such. He rehabilitated in his own way, on his own terms, how he had always lived, and then his heart became so open, so weary with that sense of distant relief, that it stopped, broke under that, I hope serene, pressure. It was not a flaw in his essence that my father had to rehabilitate from, it was the flawed characterization that this society gives to black men of his stature that he had to unravel and rehabilitate from, and supersede, and forgive. My father was the first criminalized griot / poet I encountered, and he’s why all my heroes (including him) have a dangerous temperament. I see a kind of intelligence in being dangerous as a black man in this society—I see in it something I can trust more than docile black middle class obedience.

---

As I reconciled the many sides of my father, I had to face the way some powerful black artists are sabotaged or taught to sabotage themselves as an element of style, almost in order to be relevant to this society, one that craves and eats our suffering. I came to realize that the black poetic spirit in its highest iteration is more criminalized than any felony we know. One way or another owning it can cost you your life. It is the black griot poet spirit that inspired Amiri Baraka to lead the Newark riots in 1964, a role for which he was beaten nearly to death, nearer to god than thee, and thrown in jail where he too may have perished had it not been for Allen Ginsberg showing up to demand his release. It was the black griot spirit, unbroken, that led Malcolm X to spend his time in prison mastering the language, and to be killed for exciting his people with speeches, words, militant poetry, nearer to god than thee. Even poetry preaching love, in MLK’s case, cause for murder, now he’s nearer to god than thee. In Tupac’s case, embodying a new poetic form, cause for murder, brought him nearer to god than thee. In Fred Hampton’s case, speeches on the importance of solidarity and education and anti-imperialism, caused him to be murdered by the government, he rests nearer to god than thee. And then we have someone like Etheridge Knight, who became a poet while in prison and lived to tell it like only a griot can, he paints, taped to the wall of my cell are 47 pictures, 47 black faces… they stare across the space at me sprawling on my bunk, I know their dark eyes, they know mine, I know their style, they know mine, I am all of them, they are all of me, they are farmers, I am a thief, I am me, they are thee. Throwing black griots into prison is a dangerous and losing game for the white man, we come out stronger, and in the spirit-world we are even stronger than in a damaged Westernized vessel. The prison system, meant to pick up where slavery left off, and the accompanying assassination chessboard, accidentally rehabilitates some us into untamable poets. We come to know that we have no other choice but to uphold beauty and truth, that nothing else gives this life value. We come to rely on our memories and remember who we really are. And into the silence of those cells we learn to sing our stories. I picture my father trapped in his own freedom and narrating his way to order in a lost tribal tempo with family pictures taped to his cell wall and I make sure my picture smiles at him and I make sure to write these stories because his legacy of struggle allows my struggles to be much less severe, because it’s thanks to the spirit-science he left me with that I’m the criminal-minded pathologically tender poet I am today.

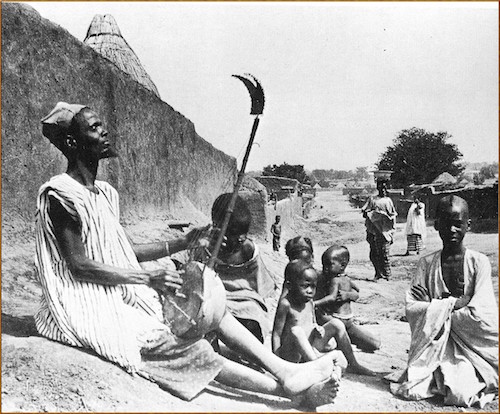

There is West African Malinke rhythm called Sofa played now for dancers, but traditionally played for horseback warriors with a string instrument called the Balon. Trained horses would perform a stepping dance to celebrate the warrior’s bravery while the warrior described the state of the battlefield. Today the dancers perform that dance and our warriors are too busy in the mimed combat of daily life to tell the story alongside us, so we tell the story and become the warriors ourselves, and become poets to tell of it, and drummers to know it by heart. For all of the West’s pathetic attempts on our lives, reparations begin in the body that can do and overcome all of these things at once without flinching. It is this strength, the strength of the griot exceeding himself and herself that has been criminalized in the West, too bad we come back stronger after every season of terror, better poets, more innocent, full of incident, brimming with will power, more and more like ourselves.

Harmony Holiday (she/her) is a writer, dancer, archivist, filmmaker. and the author of five collections...

Read Full Biography