‘Le cri vain’: On Philip Terry & Enoh Meyomesse

BY Oli Hazzard

This morning I came across a passage in an essay (Frederick Ahl’s “Ars Est Cameleer Artem,” in On Puns, edited by Jonathan Culler) which describes a scene in Cicero’s On Divination. A merchant cries, “Cauneus!,” which means "Carion figs!" The Roman general Crassus, passing by on his way to war in Syria, hears the phrase as the homophonous "Cave ne eas!," or, "Take care not to go!" A momentary chasm between the world of the merchant and that of the general is revealed through the accident of the homophone; the incidence of apparent synonymity or conjunction in fact allows for a sharp registration of difference, of indifference. Right now, there are lots of ways this story could be taken, and I’m not equipped to talk about many of them, but I am interested in the expository potential of punning it brings to light. Over the past few months in the U.K. (as in the U.S.), political discourse has become tuned to such a maddening, Steinian frequency—Brexit means Brexit means Brexit means Brexit—I’ve been particularly grateful for poems that have helped me hear and think about what I think I hear in new ways. A few weeks after the E.U. referendum, an anthology of poems responding to Brexit, edited by David Grundy and Lisa Jeschke, was published online. One of the most striking pieces included is Rachel Sills’s “Brexit Reshuffles,” an anagrammatic work which brings to mind the potent, willfully blunt political poetry of Bob Cobbing. The anagram, as a means of rhetorical exposure and ridicule, is crude, apt, and mimetic: the title describes the formal procedure of the poem, but also anticipates the grotesque charade of political position-switching which occurred in the aftermath of the vote. I find both ludicrous and curiously moving Sills’s process of re-arranging—in what seems like a dazed, livid, doodling state—the letters of key terms from the election campaign in order to try to make those words mean what they mean:

GREAT: GRATE

BRITAIN: I BIN ART

BREXIT: EX BRIT

FREEDOM: DEFER ‘OM’

HATRED: DEARTH

EUROPEAN: A PURE ONE

ISOLATION: INTO A SILO / I, TOO, SLAIN / I SAT IN LOO

NIGEL FARAGE: A GRIEF ANGEL / I ENRAGE FLAG

LEAVE / REMAIN: A VILE RENAME / AM EVER ALIEN

There is something about procedural work of this type—poetry which works with what resources it can find, and rather anxiously foregrounds the contingency of its own utterances—that appeals to me as a way of responding to public events. It suggests, with an emphasis so excessive as to be formally distortive, that the other worlds the poem wants to imagine and (distantly, impossibly) bring into being must necessarily be built from the materials of the one we have (to paraphrase a host of poets, from Allen Grossman to Lisa Robertson).

Stills’s work reminded me of a very different but related poem, Philip Terry’s translation of Dante’s Inferno, written partly in response to the coalition government’s disastrous tripling of university tuition fees in 2011. Of all the translations of the Inferno I’ve read, Terry’s satire appears to have taken deepest to heart Mandelstam’s remark that “it is unthinkable to read the cantos of Dante without aiming them in the direction of the present day. . . They are missiles for capturing the future.” In this version, Hell is re-located to the campus of the University of Essex (where Terry teaches); Dante's original cast of sinners is replaced by an eclectic mixture of poets, university administrators and members of the coalition government; the role of guide once occupied by Virgil is taken by the New York poet Ted Berrigan; and the role of the pilgrim is assumed by Terry himself. Though structurally Terry's poem remains largely true to the original—it chronicles the journey of pilgrim and guide through the nine circles of hell, punctuated by encounters and interviews with the various sinners condemned there—such modifications tell us this is a translation toward the looser end of the spectrum. Terry's version of the famous opening lines of the poem illustrates the idiosyncrasy of his approach:

Halfway through a bad trip

I found myself in this stinking car park,

Underground, miles from Amarillo.Students in thongs stood there,

Eating junk food from skips,

flagmen spewing E's...

Immediately apparent is the chatty vitality of Terry's lingo, but also its unorthodox fidelity to the music and appearance of the Italian. The strange rightness of “Amarillo” lies in its affinity with “smarilla” (lost), which concludes the opening stanza of the original; while the bizarre image of “flagmen spewing E's” was prompted, I’m guessing, by the many occurrences of the letter E in Dante's second stanza. Terry's poem is generated as much by these kinds of verbal and visual puns as by more conventional translation techniques. Unlike Mary Jo Bang's similarly irreverent 2013 translation, the vast majority of changes Terry introduces have a clear satirical purpose, and it is towards the then-government (a coalition of Conservatives and Liberal Democrats) that Terry most often points his futile missiles. At one stage David Cameron and Nick Clegg (former Deputy Prime Minister and leader of the Lib Dems, who during the election campaign had pledged, in a humiliating and much-repeated clip, not to raise tuition fees) are to be found metamorphosed into “two shapes, part human part fox,” hunted down by a pack of hounds; while Canto XIX replaces Simon Magus—from whose commercialisation of sacred things the word “simony” derives—with the then-Minister of State for Universities and Science: “David Willetts, you wanker, and your shit-brained / Followers, pick-pockets in silk suits, / Who play the pimp with HE, // Which should be a right, / and free . . . Don't you ever stop to think?” The cast of sinners also includes those involved in the War on Terror and the Troubles (Belfast is the “strife-torn city” substituted for Dante's Florence). There are some horrifying encounters. In Canto XXXIII; Terry and Berrigan reach the very base of hell, where the worst of sinners—Blair and Bush among them—are suspended in an icy landscape. Here Terry encounters the hunger striker Bobby Sands and Margaret Thatcher locked in an interminable embrace, the former continually sinking his teeth into the brain of the latter “as a famished man sinks his teeth into / A crust of bread.” Sands describes the conditions of his imprisonment on earth in these terms: “The stench was appalling, / The cells were literally covered in shite, / And everywhere you looked were flies and maggots. // It was like something out of Dante, like, / Only this was really happening, in 1979.” This gruesome (and eye-wateringly on-the-nose) passage describes Terry's intention in all its clarity and simplicity. By repopulating Dante's poem with modern imagery and allusions, he is attempting to demonstrate how hellish our own world is. Sometimes this equivalence is illuminating, sometimes it feels too easy. But what it offers consistently is something more traditional translations cannot replicate: the frisson of satisfaction a fourteenth-century readership might have experienced at the prospect of public figures being called to account, however unknowingly and inconsequentially, in their lifetime. I don’t know what to do with this feeling, with the knowledge of its necessity and its insufficiency. But I hope he’s writing a poem at this moment.

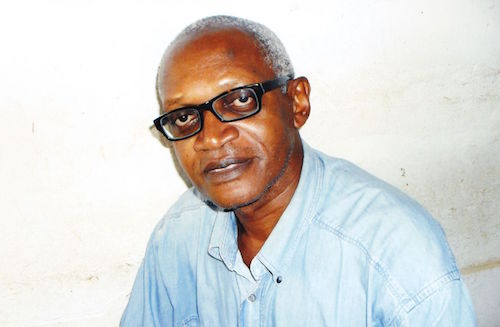

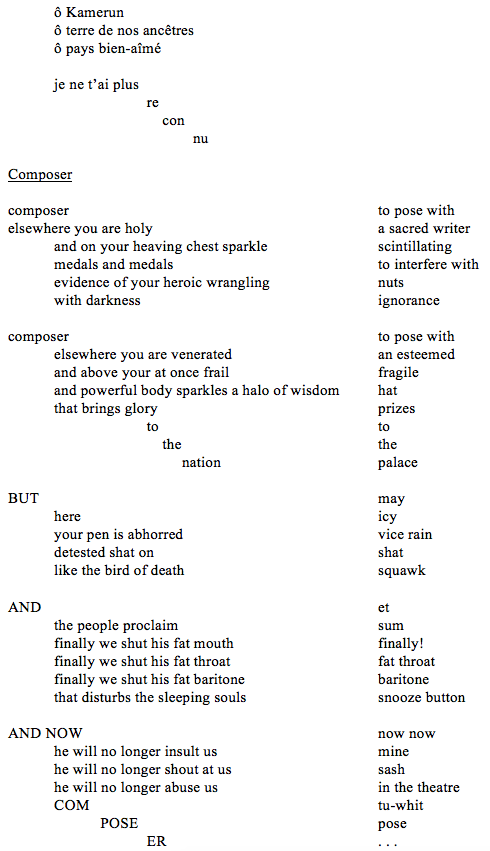

The work of Sills and Terry brings me, in a rather roundabout way, to a poet I’ve been reading a lot this year, the Cameroonian writer Enoh Meyomesse. I find Meyomesse's poems hugely affecting, for the directness of their address, their wit and ingenuity, and ability to uncover meanings and local freedoms within the most limited confines: the prison in which some of them were composed, the broader climate of censorship and persecution in Cameroon, and the self-imposed strictures of their own formal expression. (This is too easy to write.) All of these qualities are demonstrated abundantly in Poeme Carceral, a collection of poems written while Meyomesse was imprisoned between 2011 and 2015, recently translated and published as a pdf by English PEN. Meyomesse had been incarcerated, in his own words, “without any proof of wrong-doing on my part, without any witnesses, without any complainants, and more than that, after having been tortured during 30 days by an officer of the military.” His persecution was a consequence of his long-standing political activism, and the political content of his writing, which bears witness to the widespread corruption of the Cameroonian state, which has been led by President Paul Biya since 1982. Despite the terrible privation of his time in prison, Meyomesse was able to produce poems whose speed of thought, depth of feeling and good humour astonish. It is in language and the complex operations of poetic form that Meyomesse finds a means of imagining other realities than the one in which he found himself. In poem after poem he is drawn in particular to the expressive power of homonyms, which, like Sills’s anagrams, function simply and vitally as figures for the ways the same world can be made to mean different things. In “The Cursed Truck,” which describes the journey of a truck carrying prisoners to jail—“hardly a truck,” the poem states, “on which folks gaze longingly / like the truck of flight attendants on their way to Nsilamen airport”—Meyomesse converts the word “prisonniers” into the phonetically identical phrase pris sans nier, “taken without denying.” As a translator of this poem, Ollie Brock, states, the point of this gesture is not so much that all prisoners are “taken without denying”—however that phrase might be understood—but that the very term “prisoner” has embedded within it multiple possible meanings which the acts of fragmentation, enjambment, and stepped lineation serve to illuminate. The poem “Écrivain,” which I’ve translated (v loosely—a more accurate version can be found here) below, does something similar. The poem features incantatory repetitions of the title word, repetitions which recognise the fact that the term “writer” means something very different depending on the geographical location, political context, and moment in time in which it is spoken. At the conclusion of the poem, Meyomesse again segments the word into three discrete units across three stepped lines, so that the notion of “L'écrivain” itself becomes Le cri vain, or “the vain cry.” Poetry makes nothing happen, Meyomesse tells us, and that inability is a constitutive condition of being a writer; and yet the very utterance serves as its own disavowal. What these instances of formal ingenuity demonstrate is the extraordinary facility this poet has to find in the act of composition alternative ways of seeing the world in which he finds himself; and to recognise in language what has changed beyond recognition. As he writes at the end of “Arrest”:

Oli Hazzard is the author of two books of poems, Between Two Windows (Carcanet, 2012) and Within Habit...

Read Full Biography