Sadness as a Language for Other Readers

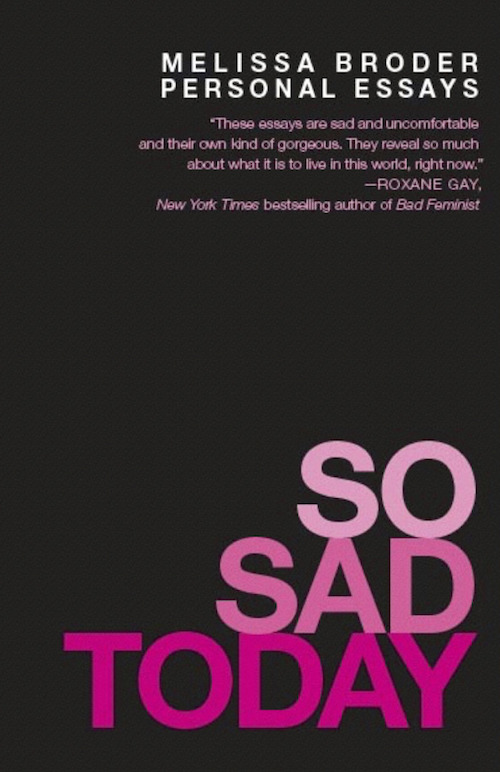

In The New Yorker this morning, Haley Mlotek considers confessional writing by women, with a look at Melissa Broder's new book of essays, So Sad Today. Mlotek weaves in a lot of writers and poets who have expressed themselves similarly:

One way to fend off isolation is to confess. Works of confessional writing, especially those written by and for women, are as much an attempt to connect as a way to unload; as Adrienne Rich once said, “When a woman tells the truth she is creating the possibility for more truth around her.” When authors like Kathy Acker and Virginie Despentes explore taboos like incest and violence, they are confronting deeply engrained ideas about sex and morality; when Chris Kraus writes about a “conceptual fuck,” she explores the limits of our understandings of female sexual desire; and when Catherine Breillat writes about pornography, she is pushing us to consider the distance between what the eye sees and what the body feels. In recent years, writers such as Sheila Heti, Leslie Jamison, and Lena Dunham have published books and essays that confront ideas of self-surveillance, self-loathing, and self-respect with humor, sadness, and detailed descriptions of bodily functions, asking their readers to consider the boundaries that get placed around representations of women. The female authors who write about their sadness—whether as searingly as Sylvia Plath or couched in jokes like Broder—provide a language for other readers, a direction for likeminded women to point themselves in, a rope to climb over a wall.

Like her Twitter feed, Broder’s essays often left me with a sharp sense of feminine recognition. I would read her accounts of heartbreak, sexual dissatisfaction, and alienation and think, Same—the solitary reader’s equivalent of a fave or a retweet. But recognition is not the same as deep connection, and Broder’s preëmptively dismissive sense of humor just as often acted as a barrier keeping me out. “Once a cucumber turns into a pickle, you can’t turn it back into a cucumber, and I’ve been pickled by the Internet for a long time,” she writes, of her Internet addiction. When describing ending a toxic relationship, she writes, “If you really love yourself, you will block and unfollow the person on all social media,” before adding, “But if you really love yourself you probably aren’t reading this essay.” In “Keep Your Friends Close but Your Anxiety Closer,” Broder talks about her “funny mask,” the So Sad Today character a disguise that allows her to feel like she can get away with bare admissions. “If I’m going to alienate you, I want to curate that alienation. I want to craft the persona that turns you off. I don’t want the real me, my vulnerabilities and humanity, to leak out and make you run. I don’t want to have needs . . . So I deflect my vulnerability into humor or ‘wise platitudes.’ ”

Read more at The New Yorker.