Williams, Sensory Deprivation, and Robert Irwin

The only thing I really know about poetry or being an artist is that in order to do it one has to somehow get out of the way to let it happen. To attend to the material rather than orchestrate it. To sit with it, let it reveal itself. Let it behave how it’s going to behave. A tall order, a difficult practice. But without it, no discovery. No discovery for the writer, no discovery for the reader.

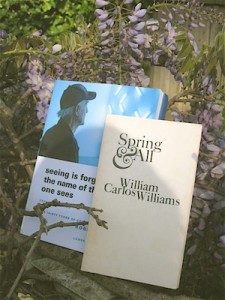

Here’s William Carlos Williams in Spring and All––

“Writing is not searching about in the daily experience for apt similes and pretty thoughts and images. I have experienced that to my sorrow. It is not a conscious recording of the day’s experiences ‘freshly and with the appearance of reality’–– This sort of thing is seriously to the development of any ability in a man, it fastens him down, makes him a–– It destroys, makes nature an accessory to the particular theory he is following, it blinds him to his world,––

...A word detached from the necessity of recording it, sufficient to itself, removed from him (as it most certainly is) with which he has bitter and delicious relations and from which he is independent–– moving at will from one thing to another–– as he pleases, unbound–– complete and the unique proof of this is the work of the imagination not ‘like’ anything but transfused with the same forces which transfuse the earth––at least one small part of them.”

Rereading Spring and All this spring much to my joy but also discovering troublesome areas I may get to in another post, it’s that how to be “transfused with the same forces which transfuse the earth” I find myself most struck with. And wanting to be struck with.

Just how does one do that.

Also simultaneously reading Lawrence Weschler’s great book on artist Robert Irwin, the great master of space and light: seeing is forgetting the name of the thing one sees, over thirty years of conversation with Robert Irwin, expanded and recently republished by UC Press.

Robert Irwin is known for periodically removing himself from society, spending great expanses of time in his own head. Early on, in 1954, by isolating himself in Ibiza, in a small cabin in which he did not converse with a single fellow human being for eight months. Then later, in the ‘60s, for spending 10-12 hours alone in his studio (few personal relations, marriage falling apart) staring at two lines he’d placed on a monochromatic canvas, periodically falling asleep, waking, back asleep, moving the lines 1/8 of an inch at a time to see how that changed the composition, the light and space, and thus, the presence of presence, of phenomenological being he was after.

And then, in the late sixties, working with artist James Turrell and Garrett Aerospace Corporation, where environmental control systems for NASA’s manned space flights were in the works (first moon landing only a few months away!). This activity resulted in a sort of unlikely yet highly intriguing collaboration between Irwin, Turrell, and a Dr. Ed Wortz, head of the laboratory.

All three were intrigued by a human being’s perceptual experience of environment. Hours of conversation ensued, and from these hours, several experiments, including an anechoic chamber, a sensory deprivation room in which they would each go in, separately, for 6-8 hours at a time, experiencing powers of perception, with no other goal, no “product” to come of it.

The anechoic chamber they used was in UCLA, suspended so that earth rotation was not experienced, no light, no sound. Irwin explains, “You had no visual or audio input at all, other than what you might do yourself. You might begin to have some retinal replay or hear your own body, hear the electrical energy of your brain, the beat of your heart, all that sort of thing…. There were all kinds of interesting things about being in there which we observed, but the most dramatic had to do with how the world appeared once you stepped out. After I’d sat in there for six hours, for instance, and then got up and walked back home down the same street I’d come in on, the trees were still trees, and the street was still a street, and the houses were still houses, but the world did not look the same, it was very, very noticeably altered.” Soon they administered the same time period in the chamber on 25 volunteer subjects, who all reported the same intensified perceptions.

Here’s Irwin again on his experiences of re-entering the familiar world: “You start spending more time making a tactile read, building your world in that black, soundless space with information from those other senses, so that when you come out, that shift simply persists for a while, it continues to be honored, and you take in different degrees of information. And we all know that the complexity out there is… we might as well say infinite…”

And in Turrell’s notes in the documentation of the collaboration there is the quintessential Blake quote: “If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.”

In coming posts I hope to continue this exploration/inquiry, how to cleanse the doors, how to see, how to experience the untapped perceptive abilities awaiting, dormant for the undoing. Would love to hear (sans drugs–– been there, done that) of other experiments, methodologies, processes….

The daughter of radio station owner-operators, poet, editor, and translator Gillian Conoley was born...

Read Full Biography