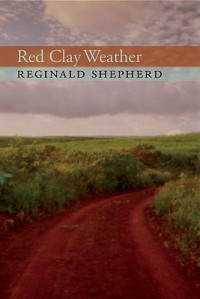

Reginald Shepherd (1963-2008)

A former Harriet poet, Shepherd’s sixth collection was published posthumously by the University of Pittsburgh Press earlier this year. Though this is Shepherd’s work, the book was edited and structured by his partner Robert Philen. I felt it was more than appropriate to respond to the book as a tribute to a writer whose words on Harriet were as complex, provocative and intelligent as his poetry.

In Philen’s opening remarks, the following paragraph guided my journey through Red Clay Weather:

“Among other things, Shepherd has always been an elemental poet. His work abounds with the imagery and motifs of water and fire, and while those elements are important here, it is air and earth that are the most dominant elements in this collection.”

Indeed the language highlighting the tactile and the olfactory shape a consciousness of the body in decay — the speaker continually acknowledges “this elegant, unkempt earth / of rust and dust, smashed cat and armadillo / roadkill, abandoned pickup trucks / blocking the berm.” The overheated car, the polluted forest, “summer and the sublime / come apart in his hands, a clutch / of crumbled leaves and sun-burnt myths / in cracked mud.”

It may be easy for readers who knew of Shepherd’s health problems (he succumbed to cancer) to “read” the imagery of deterioration as a type of mirror, but they should resist that impulse since Shepherd usually aimed for complexity. Those are not mirrors but studies of the stages of life, of perseverance and transformation — evidence of sustained value: “Oh, destroy it / so we can use it again.”

And to keep the collection from surrendering to a dark emotional tone, Shepherd throws in the celebratory, almost spiritual poem, “In Bloom” — the irises “exchanging molecules” with those who smell them, overwhelming the room with perfume, “scattering / what the surfaces give away: the / pigmented muscular curtains part, / make room for all that bountiful, our / open hands flowering between us.”

Red Clay Weather is divided into two parts, the second heavy with the Greek myths that Shepherd repeatedly embraced in his work — Achilles, Orpheus and Narcissus, among them. He was a classicist at heart who made no apologies for his “hero worship,” and who remained unfazed throughout his career by critics who argued that his work could endure without these allusions and tropes. It was a type of censoring that, thankfully, Shepherd never listened to.

Part One, however, leans more explicitly toward the personal and autobiographical. Though Shepherd minced no words in his stance about writing the gay black body into the poetry (“I have always intensely disliked what I call identity politics, the use of poetry to assert or claim social identity,” he wrote in his evocative essay “The Other’s Other: Against Identity Poetry, for Possibility”), he didn’t shy away from exploring his difficult youth in his work. “Mother Was No White Dove” (but she’s described as “the clouded-over night” and “a murderous flight of crows”), situates the woman within a life of distress and hardship, and also, I argue, racializes her. The poems “Flying” and “Falling” move from the lyrical to the narrative with lengthy lines rich with detail about the difficult, impoverished times, events Shepherd revealed with unflinching honesty in his extraordinary essay “To Make Me Who I Am.”

The first half of the book ends with a substantive prose poem “Some Dreams He Forgot,” each paragraph an example of fear and anxiety funneled into the cryptic and symbol-heavy dreamscape. Here’s one nightmare that other writer might relate to:

“Dreams in which I write the perfect poem, painstakingly setting down each word, but forget it when I wake up. Dreams in which I wake up and write down the poem I’ve just dreamed to make sure that I won’t forget it, but then I wake up again and realize that I was still dreaming. Sometimes a phrase or a line lingers in my head, and it makes no sense at all.”

The following is the poem that most resonated for me in light of Shepherd’s afflictions and early demise. I remember how news of his death was not altogether unexpected, but a shock nonetheless, to the poetry community especially. So it was particularly painful to watch how two days later news of another literary death (David Foster Wallace), compounded the sense of loss and devastation. And I can’t help but recall the opening sentences of “Why I Write,” the final essay in Orpheus in the Bronx: “I write because I would like to live forever. The fact of my future death offends me.”

To Be Free

It’s winter in my body all year long, I wake up

with music pouring from my skin, morning

burning behind closed blinds. Dead

light, dead warmth on dead skin

cells, the sky is wrong

again. Hope clings to me like damp

sheets, lies to my skin. As if I were a coat

wearing my bare body out on loan,

accumulated layers of mistake

and identity, never mine.

I’m dressed as so many people, well known

wrong me reviving my old heresies,

praying them into sunset

and the weather they’ll become:

folding them into snow. The forecasts

are always accurate, the only promises

kept. Foolish Narcissus frittered himself away

to a flower, Echo suffered down her life

to someone else’s syllables wind throws

away. Neither knew how to survive

the period style, long days

in their disastrous completeness.

I won’t let the myths outlive me, won’t drown

in my nostalgia for the here and now.

I lie down in the imperial purple

as if I were the sun, lay my body down

in distance. Correct all deviations

and make the moon change its tune.

Rigoberto González was born in Bakersfield, California and raised in Michoacán, Mexico. He earned a ...

Read Full Biography