Who: Andrew Zawacki

What: Paris graffiti

When: June, 2012

Where: Paris, France

“Open Door” features audio, video, and online media to document dynamic interactions between poetry and its audience. “Open Door” showcases performance, scholarship, and engagement outside the usual boundaries of slams, workshops, and book publications. This week: Photograffiti in Paris.

***

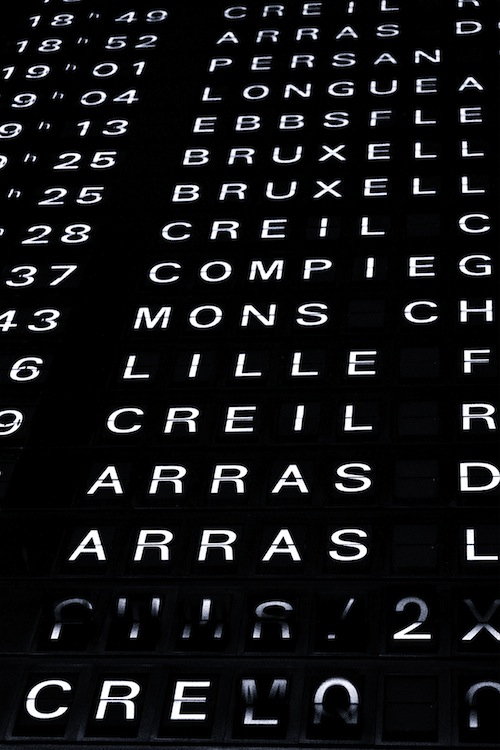

What I love about graffiti is the uncanny sense that a body was there—physical, if with a faceless face—, to lay the message down with its own two hands. While gorgeous in a mandarin way, most other contemporary signage in Paris—from the train timetable at Gare du Nord

to satellite placards at CDG1

—is riveted into place or laser-fit, flush with an attendant aesthetic of top-shelf kerning and bulletproof lines, to shimmer in a pair of aviators, à la Tron sashaying the autobahn and kryptonite and chrome fenders, polished with a chamois cloth, to the tune of Portishead’s “Nylon Smile” or Interpol, “Untitled.” But graffiti is embodied writing—acoustic, analog—, an unplugged choreography of shake, strafe, sweat and scram, the urban counterpart to Cy Twombly’s brushed articulations of mythical scripture in motion. An ambidextrous, hi-lo tableau: fine art with one hand, in the other roach repellent—though the arm that drew these arms is already a phantom limb.

Whatever the mechanical claptraps, narcissism, hubris, or political convictions involved, the graffitist is a gymnast, maybe even a contortionist. Propositions offered in propria persona—though the scribe has long since skedaddled. For the body is no longer present, at the moment of reading: an “absent visible body,” as the late Akilah Oliver described the graffitist ghost, his

writing comparable to guerilla tactics—to strike, retreat, in striking, to change the landscape, to alter the public, i.e. political, space, to force a discourse outside of the script, to flip the script—the body is present in the visibility of the language, in the style, in the technique(s) that inform the writing, but the actual body is coded, is phantom, is transient and nomadic, therefore evading not subjectivity, but ownership and control over that body, over the writing itself, since the author(s) are apparitions.

An elegy for her son Oluchi McDonald, as well as a collaboration with the graffiti he signed “LINKS,” Oliver’s poem “The Visible Unseen” is a beautiful braid of theoretical fragments and color photos that meditate on the relationship—less manifest than appropriately amorphous—among “graff,” grief, and the redistribution of socio-cultural identity. “who is the nomadic body,” she asks, “who by its very evasiveness, transmutes a stationary location? this body that is not a locatable physical subject.” Perhaps this retreat of a verifiable author—with which Plato reproached all writing—accounts, in part, for the poignancy of the after-dark mark. If nothing else, the meaning of graffiti is never less than the name—be it authentic or disguised—of the person who tagged it: a trace of former presence. The author’s signature, in his abstention or withdrawal, is what graffiti signifies.

Graffiti—diminutive of graffio, “scratch” or “scribble.” But why little? Even miniscule, in incorrect English, a prima donna ditty inked to a plank in a suburb called Creil, graffiti moves toward the middle, the major, a makeshift lintel gracing a portal, inviting us to take a gander at its delusions of grandeur. Aswim inside an aerial shot, as if it needed some space to say its peace, graffiti wonders Who WAtcH ME? even when we’re not.

If graffiti is a city’s subconscious, frequently its libido or Id, striving to cut the superego down to size, it nonetheless boasts a massive, missive ego of its own. Bravura, bravado, braggadocio, brogue—thy given name is graffiti. Case in point: the TER track, where it exits the tenth, is a tie-dyed ziggurat.

Every tag a biff of sabotage: no coincidence that an aerosol can, in French, is called a bombe. This hardcover, quasi-cuneiform corner of Jussieu, a university campus in the fifth arrondissement, is nothing short of hyperbolically threatening: throwback sci-fi, pretentious portentous—even my photo of its spine looks fake, from mirrored footer to the string of galactic code. IMP EB9, RE 108: android chips or supernovas, coordinates for a televised nuclear strike? It’s level eleven of a PlayStation game—CGI windows, dot-matrix walls—or HQ for the bad guys in a manga melodrama. Did the graffitist airbrush the storm clouds, as well, and the diving bird of prey? Are the titles a Rolodex of telexed tags?

Graffiti is less subversive, or “sub-” anything for that matter, than Surreal, from the preposition sur, for “above” or “beyond”—over the top, as we say. Dreamlike, running without interruption, viral and spiraling out of control, graffiti forgoes logical segues, the genetics of what goes where, why. Be it logorrhea—uninventive and ugly, simply to foul or deface—or the lowghost at its pretti- and prissiest, graffiti possesses a mania to make itself everywhere (to use Dickinson’s term for publication) “Ostensible.” It wants to override the system, overwrite the grand narrative, turn writing on a wall into The Writing on the Wall.

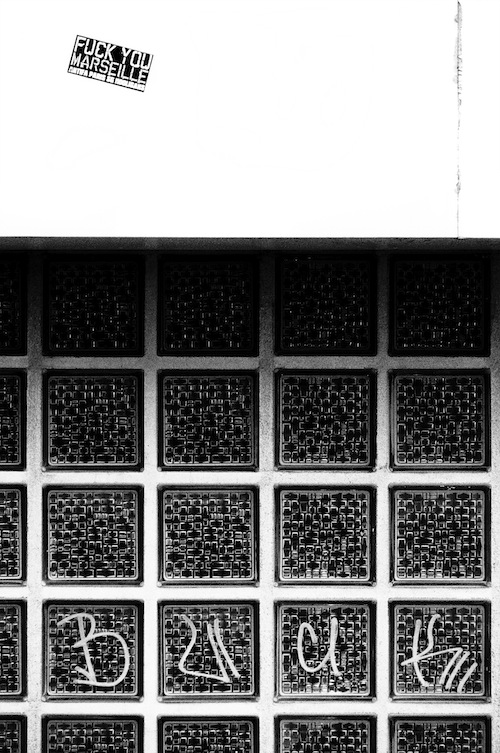

Such blatant scrivening is concerned with “upsetting and reconstituting the visual forms of public discourse,” Oliver claimed, “it advertises difference and insurgency, illegality, vandalism, distraction not just in its placement, but in its aesthetic, in its attention to the shape of the emotion, to the act of naming.” Just ask it to cooperate, say something reasonable, parrot discursive conventions or copy the patterns of acceptable display, and graffiti would prefer not to. Inherent in its default defiance, though, is a fever for fracas that’s periodically pointed inward no less than out: by no means does graffiti imply a unified front. There are toughs and turf wars, internecine flexing, and intercity rivalries, with soccer among the hottest arenas for adding serious injury to insult. Subtitled Antifa Paris SG Hooligans, this seemingly bromidic sticker, upper left—less graffito than graphic design, a tag for the age of mechanical reproduction: McGraffiti—is not a joke. Antifa for anti-fascism, SG for Saint Germain: more than mere football partisanship it’s a promise, if you’re a club Marseille supporter, to break your face.

La Ville de Paris and many mayors’ offices are increasingly allotting, even financing forums for permissible graffiti—until recently an oxymoron. (Example: I recently found myself amid a Paris Zone Libre live painting session in Belleville.) But the work of non-supported, some would say un-co-opted graffitists is still a far cry from marginal or peripheral, whether the artists hail from the projects or not. Graffiti lurks at the city’s center, as interloper or Trojan Horse, a paralinguistic terrorist, spelunking the cells or scaling the spires of our blithe cosmopolis—the visual genus of parasites, French for the static that interferes with a signal. As if every avenue in, or out, must pass through a door of anonymous allegation.

Which isn’t to say that graffitists don’t guard their identities closely. Who is Banksy anyway? His agent won’t comment, The Onion claims he’s a near nonagenarian Old London lady—he’s practically a Bristol stencil himself, applicable to any facade. His name is counterfeit, but he’s hardly a “phony” in the sense that Holden Caulfield meant, or that Gavin Polone intended when disparaging Michael Moore, or even a “real phony,” the phrase her own agent used to describe Holly Golightly. The alias preserves anonymity, in turn protecting the work. DeLillo’s avatar, whose specialty is hitting MTA trains that roar up onto aboveground tracks, goes by Moonman 157: one part astronaut, or lunatic, or Romantic who does his nozzle dazzle exclusively by reflected light, and one part postal address—although no one can find where he lives. A principle of restlessness, a ghost in the machine if ever there was, Moonman has molded his sobriquet, too, by corrupting propriety—his name. A Bronx backstreet teenager, it turns out Muñoz drinks Perrier, “in pretty green bottles. He believed in going elite whenever possible.” French is evidently synonymous with privilege, excellence, classiness, for this subway punk with a taste for natural mineral water, “renforcée au gaz de la source,” that hisses and spits like a spray paint can, finger on the valve. Speaking of supreme fictions, of apparitions of faces in a crowd: Moonman’s magnum opus is miraculous to his neighborhood of mourners and questing souls. A trompe-l’œil billboard gauzed with hydrofluorocarbon color, lit of a sudden at night, by a train, it lifts a dead girl back to life, for a second. Then she’s gone again.

Andrew Zawacki is the author of four poetry books, including Videotape, due in spring from Counterpath. He’d like to thank Cathy Wagner for reminding him of “The Visible Unseen,” as well as for sending him to this 2009 interview with Akilah Oliver at BOMBLOG: http://bombsite.com/articles/4539.

(If you would like to pitch an “Open Door” feature concept, please e-mail [email protected] with “Open Door” in the subject line.)

Andrew Zawacki is the author of five books of poetry: Unsun : f/11 (2019), Videotape (2013), Petals ...

Read Full Biography