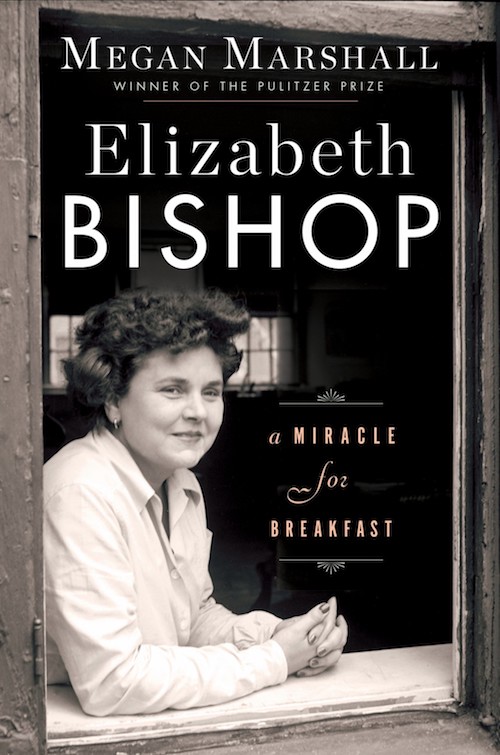

New Elizabeth Bishop Biography Mirrors the Distance & Reserve Found in Poet's Own Work

Megan Marshall’s biography of Elizabeth Bishop "focuses more on the life than on the literature," writes Troy Jollimore about Elizabeth Bishop: A Miracle for Breakfast, forthcoming from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. "And Bishop’s life, like everyone’s, was at times difficult and messy, if not as visibly and extravagantly tumultuous as many of her poetic peers." More at the Washington Post:

Unlike many of those poets — Lowell, of course, but also Allen Ginsberg, Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, John Berryman and others — she kept the difficulty and mess out of her writing, permitting the poems only to gesture toward them in indirect, encoded ways. Her work was never about self-display, let alone self-dramatization. Beneath the surface, though, lay considerable complexity and genuine drama.

She conducted love affairs with multiple women, sometimes overlapping, sometimes involving concealment and secrecy, during a period in which being openly gay was difficult and potentially dangerous. The most significant romantic relationship of her life, with the Brazilian architect Lota de Macedo Soares, ended with Soares’s suicide in 1967. Bishop herself acknowledged that she drank too much, putting a strain on many of her relationships; she frequently promised her partners that she would stop, but was not able to. It may have been, in part, her way of dealing with the scars of a difficult childhood: Her father died when she was an infant, and her mother was committed to a mental institution when she was 5, leaving her in the care of more distant relatives, feeling homesick and abandoned.

Marshall’s book makes use of some previously unavailable materials, including letters from Bishop to her psychiatrist and to three of her lovers, and as a result is able to offer a more detailed portrait than existed before of the romantic relationships about which she could not be fully open during her life. But its portrait of the poet still feels somewhat remote, mirroring the control, distance and reserve Bishop insisted on in her work. (“Some surrealist poetry terrifies me,” Bishop once wrote, tellingly, “because of the sense of irresponsibility & danger it gives of the mind being ‘broken down.’ ”).

Read the full review at the Washington Post.