London Review of Books on Ern Malley, Doris Lessing, & "Hoaxer's Backlash"

Ian Hamilton explores the highish and lowishness of the literary hoax in a "Diary" for the London Review of Books. As a long-ago "anonymous hack" for the Times Literary Supplement, Hamilton used to drum up rather flimsy content when news was slow: "The idea was to mop up publications which were not considered worth full-scale reviews but which nonetheless had to be ‘covered’ by a journal of record such as ours," he writes. Hamilton went so far as to cobble together very famous lines of poetry in order to submit to "one of those ‘Poems Wanted’ publishers who advertise in all the weeklies." The composition was accepted, with the promise the author might pay for eight copies to hand to his grandmother when the anthology ("Best Poems of 1969, or whatever year it was") appeared. "Although it wasn’t spelled out, the deal was clear, no purchase, no publication. We calculated that with, say, two hundred poets buying eight copies each, this rather shoddily printed anthology would chalk up a decent profit before a single copy reached the shops, if shops indeed figured in Mr Daley’s plans." He then went on to rake the editors of said book over the coals: "So we wrote it all up, mingling tired mockery with almost-prim reproof, and bunged it into the column during a slack week. There was much applause all round, as if we had dealt the philistines a telling blow."

Hamilton was more concerned for the swindled poets than anyone else, and eventually suffers from "hoaxer's backlash":

After all, who had we damaged, if damage had been done? Not the publisher, certainly: poetry might be a tidy little earner if you play it right but Arthur could as easily switch to monogrammed nappy-liners or one-legged tracksuits. By the time our piece appeared, he had probably already diversified, moved on. No, the most likely victims of our little jape were the two hundred ‘poets’ who had no doubt been quite happy with the way things were. . . .

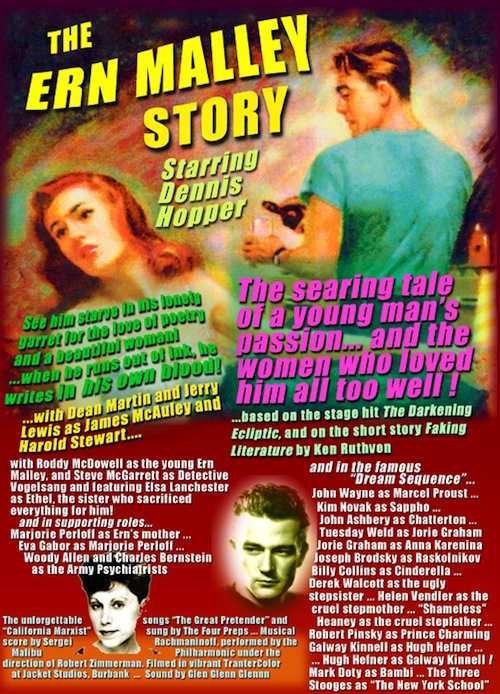

Most fun in all this is that Hamilton invokes our favorite literary hoax, Ern Malley!

Do all hoaxers end up feeling a bit wretched, after the event? Did the inventors of Ern Malley experience a few spasms of discomfiture after their spoof poet had taken the Australian literary scene by storm? I suppose not – after all, this was a high-minded hoax, an act of Criticism, really: its authors could boast that there was nothing in it that was petty or vindictive.

Read all about Ern Malley in Jacket #17's Special Hoax Issue. Ah, but the point for Hamilton is the newest literary hoax to cross his desk, that of Jane Somers AKA Doris Lessing.

On the public front, Lessing contends that she has revealed important truths about the state of publishing and reviewing: it’s all so mechanical and yet it’s all so name-fixated – by means of her hoax, she has established that a known author gets more respect than an unknown. Well, thanks for telling us. She also wanted to help these said unknowns by demonstrating that even somebody as gifted as herself could, when rendered nameless, be treated with institutional disdain. And, as if all this were not sufficiently confusing, she (parenthetically) rather liked the idea of exposing the shoddiness of her regular reviewers. ‘Some reviewers complained they hated my Canopus series, why didn’t I write realistically, the way I used to before; preferably The Golden Notebook over again? These were sent The Diary of a Good Neighbour but not one recognised me.’ That’s pretty shoddy, you might think; after all, these people are supposed to be her fans. A sentence or so later, though, Lessing herself lets these (and, I should say, all other) dunces off the hook: ‘it did turn out that as Jane Somers I wrote in ways that Doris Lessing cannot ... Jane Somers knew nothing about a kind of dryness, like a conscience, that monitors Doris Lessing whatever she writes and in whatever style.’ And it is here that the girlishness intrudes. What she seems to be saying now is that when Doris Lessing becomes Jane Somers she stops being Doris Lessing; it is only afterwards that she becomes Lessing enough to blame people for thinking Somers is not her:

Some may think this is a detached way to write about Doris Lessing, as if I were not she, it is the name I am detached about. After all, it is the third name I’ve had: the first, Tayler, being my father’s; the second, Wisdom (now try that one on for size!), my first husband’s, and the third my second husband’s. Of course there was McVeigh, my mother’s name, but am I Scots or Irish? As for Doris, it was the doctor’s suggestion, he who delivered me, my mother being convinced to the last possible moment that I was a boy. Born six hours earlier, I would have been Horatia, for Nelson’s Day, what could that have done for me? I sometimes wonder what my real name is; surely I must have one.

Find out what Hamilton really thinks about the whole thing here.