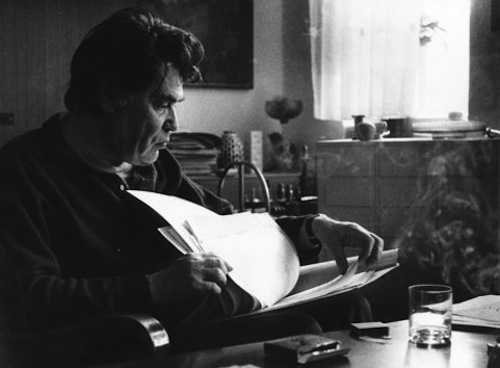

Death, Translation, and Ernst Meister

Rumpus reviewer Alex Estes takes on the new translation of Ernst Meister's In Time's Rift, discussing this German poet's thoughts on what it is that comes after life. Miester, who died in 1979, has been resurrected by translators Graham Foust and Samuel Fredrick, who, in Estes opinion, do an admirable job balancing the spirit of the text with its literal translation:

Where one translator may find themselves wanting to help the reader grasp the concepts while sacrificing the beauty of some of the best lines, another might focus too heavily on the poetic and hang the reader out to dry. Foust and Fredrick have struck a great balance between these two approaches. They state in the introduction that “Translation is impossible.” They are quite right. There will be loss and this loss can be found in a few places in the collection. But upon close consideration, the loss is justifiable almost every time. For example, “Es will sich/im Toten/das Nichts verschweigen” is translated into “Nothingness wants/to conceal itself/in what is dead”. In meaning, this is essentially what was written in German. What is lost is a bit of Meister’s wordplay. Im Toten does mean in the dead but it’s also used in German to mean blind spot. The phrase is able to pull double-duty in the German. In the English what goes missing is the slightest touch of warmth.

In the translated lines there exists nothing relating to people, nothing warm or human. It is only a touch, but in a collection so devoid of it, a touch can be all that’s needed. For it is only animals that have blind spots and humans who speak of them. One would not say that a boulder or a tree has a blind spot. And maybe boulders don’t experience death, but trees do. Here, though, the problem was unavoidable. The English term for blind spot is blind spot and the German term is not. Simple as that and therefore forgiven...

Learn more about Ernst Meister and his translators here.