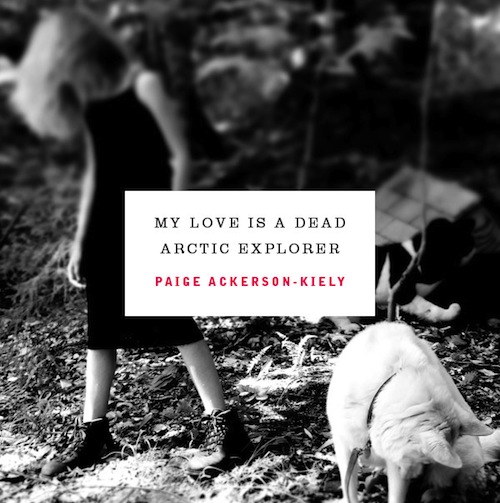

Michael Robbins Reviews Paige Ackerson-Kiely's My Love Is a Dead Arctic Explorer

Michael Robbins wrote about Paige Ackerson-Kiely's new book, My Love Is a Dead Arctic Explorer (Ahsahta Press 2012), for the Chicago Tribune, beginning with the blanket, "Most poetry published is mediocre at best, and often plain awful" (could be, could be!), but moving to "Ackerson-Kiely is setting the woods on fire." More:

Here's the end of a prose poem called "The Meteorite":

This is how a night goes insane. It is brutal and you will surely die even though you are strong and beautiful and I love you so much. There is no way around it. I used to be a jackass to strangers, just brushing past them on my way to the market to buy bottled water and limes — but those strangers were not being discovered, and if they had a meteorite in their backyard from which they chiseled tools important to their survival, I did not know of it. I did not help myself.

A friend once described someone's work to me as "what poetry would be like if the earth had no atmosphere" (that's a dig). Ackerson-Kiely's poems are what poetry should be like, given the atmosphere we have — life-supporting but containing the highest levels of carbon dioxide seen in three million years. Human interference has made her corrosive:

I became aware of one or two things: I did not want to keep the baby, this was already on the list, but I wanted you to want me to keep the baby, and I wanted to keep the baby for you. I wanted not to keep the baby, but if you did, to name her something serious, like Dolores, with its root of pain and grief, which, I suddenly recognized with a fair amount of surprise, was exactly the name of what we already had between us.

How much better this directness is than Ackerson-Kiely's infrequent dalliance in the flummery of purple redescription, a popular malady to which not many poets have acquired immunity. "The dust chirring behind the car choiring up in brief staccato" is just the fancy version of Mad Libs that plenty of poets belch forth like exhaust pipes. But "the great limitations of love plainly announced on the elementary school billboard: Early Release" is a testament to the uses of poetic materials for thinking and seeing, as are these lines from "Ars Poetica":

The sheets lay flat upon the beds. Not once had they been tied to a bedpost, let from a window and carefully slid down until a foot touched the grass below. All grass is a relative of the poet Donald Justice. In fact, I cannot think of grass without imagining how it goes yellow secretly, and at the root.

Or these, from "Cry Break":

I thought of the way the singers that particular station favored created a chest-pulse, commonly known as the cry-break in Country Music, and how I had, while doing the laundry or tending that which required my tenderness, until that moment, been really listening for it.

Ackerson-Kiely returns often to tools in her poems, and it is apparent that poetry is a tool for her, one of those important to survival. None of this estranging the familiar — her poems make the familiar more familiar. The kids never eat the lunch you pack, and you are a native of gas-station buzz, and the flight attendant says, "Other way, honey." Her poems resituate us in our home, here — in meadows and convenience stores and airplanes and bars and motels and mountains — and remind us to be absolutely shot through with anxiety and uncertainty and desire. . . .