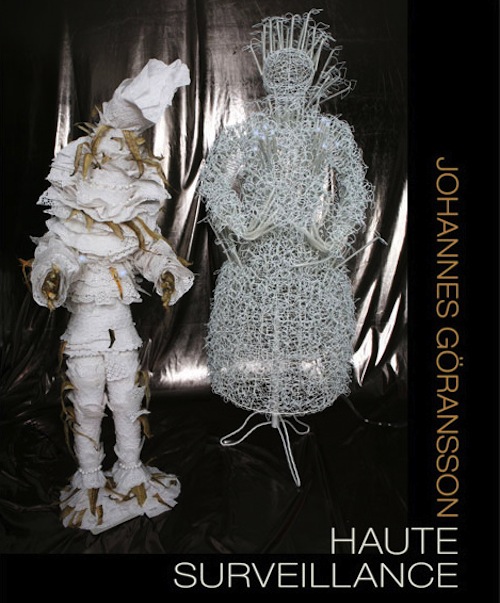

John Yau & Blake Butler Both Review Johannes Göransson's Haute Surveillance

A couple of good reviews in for Johannes Göransson's new book, Haute Surveillance (Tarpaulin Sky, 2013)! First up, John Yau writes for Hyperallergic that HS is a book that "shares something with Whitman, Monique Wittig, J. G. Ballard and Dostoevsky’s 'underground man.'" Futhermore: "Göransson, who has previously published five books and translated the Swedish poet Aase Berg into English, is one of the few contemporary poets who bring disgust into his writing without cloaking it in irony or some other self-protective device."

In addition to the Virgin Father and Mother Machine Gun, Göransson has populated Haute Surveillance with the Starlet, Father Voice-Over, the Black Man, Sister Dark, the expresident, the Soldiers, the Genius Child Orchestra, abortionists and anti-abortionists. These and other archetypes keep reappearing in unexpected ways. Shelley Duvall, in The Shining, drops in from time to time. Various movies (Hiroshima Mon Amour) and books (In the Penal Colony) get mentioned.

What the poets associated with “Flarf” recognize — and the literary mainstream still ignores to a large degree — is that the Internet has flattened daily life into a constantly swirling, cacophonous mosaic. Instead of extending that jarring, two-dimensional world into poems, Göransson has absorbed Frank O’Hara’s “intimate yell” and made it all his own. Haute Surveillance is a world of wounded voices.

I have a nightmare about a girl covered with blood and when I wake up sweating my wife tells me a fairytale.

For all the disparate information that Göransson brings swiftly and confidently into play, Haute Surveillance is not a collage. None of it feels arbitrary, which is nothing short of miraculous. At the very least, the author’s ambition was to write a new “Song of Myself” addressing these confusing, contradictory times in which we are at war, as well as to construct memorable situations without resorting to a plot or other familiar literary devices. He succeeded at both. His reasoning is simple and direct:

Sometimes I want a room of my own, but mostly I just want a room without all these corpse-patterned wallpaper.

Blake Butler also wrote about Goransson's book for Vice:

...Taking its title from a Jean Genet play of the same name, it’s kind of like a novelization of a movie about the production of a play based on Abu Ghraib, though with way more starlets and cocaine and semen.

One of Haute Surveillance’s many sources of power is how it forces other artworks into its bodies and reconstitutes their mythologies into an even deeper unknown. The novel is set in part, for instance, in what seems to be the hotel from The Shining, which has been remodeled into some sort of prison where the prisoners are forced to perform acts of theater and unusual sex. The only direct reference to the The Shining itself, however, both reveals the aesthetic contrivances of the production of the film, while embellishing the method used to provoke the veils of horror. “All of The Shining was shot with sets,” Göransson writes. “The snow was salt. It was 110 degrees inside the soundstage. The air was saturated with gasoline fumes. The cameramen and camerawomen wore gasmasks as they ran through the rooms chasing the little boy. There were antennae in the walls. The production crew built up an entire hotel inside. Nothing was fake.” These accusations manipulate the reader’s previous understanding of a terrifying setting and bend it in such a way that destabilizes the whole foundation of our memories and expectations of aesthetic experience.

This effect is threaded throughout Haute Surveillance. The reader is somehow being toyed with, being watched. Göransson presents his ideas and images often by explaining their symbolism before their appearance—the voiceover before the actual speech. The book is composed of countless chopped up scenes and fragments woven together in such a way that the book itself seems to have been beaten apart and reworked in some prisoner’s dementia. Timelines are for shit, as are the boundaries of the settings, the present fumbling right alongside both the future and the past. Like when explaining how his youngest daughter got pregnant and gave birth to six babies at the same time from licking a dirty towel, he explains, “This daughter goes by the fancy name The World. But we don’t use that name.”

Butler also includes an excerpt of the book. Read both reviews.