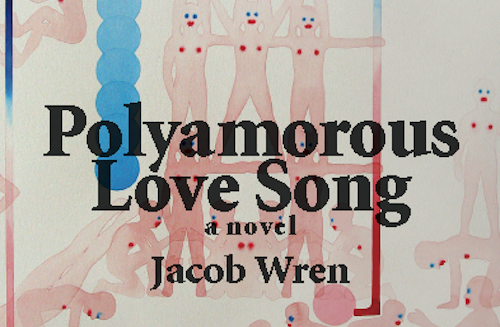

Examining Art in a Larger Sense: Jacob Wren's Polyamorous Love Song

Writer of the poets Jacob Wren has a great interview up at BookThug in honor of his newest novel, Polyamorous Love Song, which seems in dialogue with the likes of Chris Kraus, Michel Houellebecq, and Javier Marías, according to interlocuter Malcolm Sutton. Wren responds:

One through-line might be that most of the writers I love most aren’t afraid of ideas. (To the list you began ... I might also add: Juliana Spahr, Alvaro Mutis, Jan Potocki, Renee Gladman, Nicholas Mosley, Lynne Tillman, Wolfgang Koeppen, so many more.) There is perhaps a strain of North American literary anti-intellectualism that I am strongly reacting against. For me, ideas don’t need to be hidden within or behind narrative, you can have ideas and narrative side by side. The banal writing class cliché ‘show don’t tell’ seems, to me, to conceal an ideology I find almost pernicious. If you have something you want to say, concepts or insights you feel are worth conveying, I see no reason not to state them clearly. I use the word ‘pernicious’ because, I suspect, a rule against speaking out in literature is in some way connected to a reluctance to speak out in other areas of life.

Then there is the fact that I read all of these allegedly ‘obscure’ authors, authors that deserve to be better known but for whatever reason aren’t. For me, reading is always an act of creating one’s own personal literary canon and then trying to put it into play, put it into some sort of dialogue with the world. (I also wonder if there are writers in Europe and Latin America that I would like even more than the ones I know, but that I cannot read because they haven’t yet been translated. I have tried to learn other languages but always fail almost completely.)

As well, I’m not only in dialog with literature, but also with visual art, theory, performance, cinema. One of my desires for twenty-first century art is that more of the barriers between the disciplines continue to break down. That, for example, artists working in conceptual poetry would know more about what’s happening in conceptual dance. I think, because of the way different art forms are taught, and also because of funding structures, there is not nearly enough interdisciplinary dialogue. Ground-breaking things begin to happen when artists stop thinking only about their own narrow field and examine art in some larger sense.

Another interesting topic:

MS: Is comedy as important to you as heartbreak?

JW: I sort of hate comedy in art. On the other hand, I don’t mind writing about, or re-imagining, the world in ways that also happen to be funny at certain moments. In fact, I am often extremely surprised by what people find humorous in my books. When I’m performing, I often feel I have failed if the entire audience laughs in unison. However, if half the audience laughs, and the other half wonders why the hell they are laughing, then maybe I have created the condition for something interesting to begin, for some debate or dialog. I want to create questions, in a sense create conflict, within the reader and between readers. If something is only funny there is not nearly enough tension. Another way of saying this might be: comedy without heartbreak would be meaningless to me, not nearly complex enough.

Both comedy and heartbreak are, of course, very much parts of life. I remember first seeing the work of Bas Jan Ader and being amazed at how he took the basic structure of seventies conceptual art and filled it with so much vulnerability, comedy and sadness. It was like he glanced at conceptual art and immediately, instinctively saw what was missing. If you can see the humour even in moments of greatest heartbreak it might very well help you survive, but I suspect the opposite is also true, and might prevent one from laughing too much at the expense of others. I am fascinated by how often humour is used as a defense mechanism or form of attack. Comedy is seen as joyous but it can just as often be overly protective or violent. As well, as I get older I become more bitter, though I definitely don’t want to be, and I keep telling myself over and over again: never lose your sense of humour. I have no idea whether or not this particular mantra is working.

It must! He also discusses sex and violence! Violins! Read it all at BookThug.