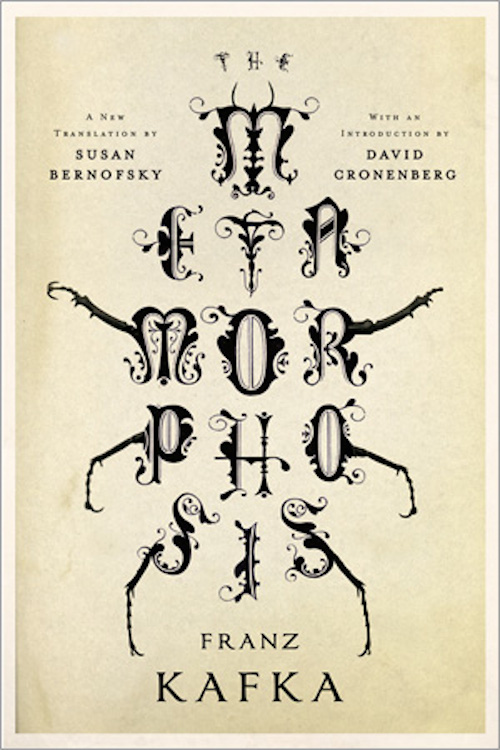

Joyelle McSweeney on Susan Bernofsky's New Translation of Kafka's The Metamorphosis

Just up at Fanzine is Joyelle McSweeney review of Susan Bernofsky's new, "fastidious," translation of Kafka's The Metamorphosis, published by Norton this year. "Wake Up for the First Time Again" is at first a comparative study:

“Als Gregor Samsa eines Morgens aus unruhigen Träumen erwachte, fand er sich in seinem Bett zu einem ungeheueren Ungeziefer verwandelt.”—FK

“One morning, as Gregor Samsa was waking up from anxious dreams, he discovered that in his bed he had been changed into a monstrous verminous bug”—Ian Johnston

“When Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from troubled dreams, he found himself changed into a monstrous cockroach in his bed.”—Michael Hofmann

“When Gregor Samsa woke one morning from troubled dreams, he found himself transformed right there in his bed into some sort of monstrous insect.”—Susan Bernofsky

McSweeney also goes into the final line:

when you re-read The Metamorphosis, it becomes a shifting topo-map, the text presenting new clefts and declivities, welling with intensities and sinking away into a diminishment one might choose to view as repose.

The same might be said of different translations of The Metamorphosis. The latest is that of Susan Bernofsky, the marvelously nimble translator of such contemporary German-language authors as Yoko Tawada and Jenny Erpenbeck as well as Walser and Hesse. As a translator, Bernofsky is as daring and precise as an aviatrix. One could say she pilots the English text, with Kafka’s sentences spreading out like a landscape just millimeters below. She moves us along the dips and rises in Kafka’s tone, surprising us with the swoops of its intensity, pulling us up short at its most painful moments, and landing, finely, neatly, on the ground. For the English and German texts are finally identical in the silence which follows the concluding paragraph.

What a bitter irony to survive The Metamorphosis where Samsa could not; in Bernofsky’s translation, the final sentence reads

And when they arrived at their destination, it seemed to them almost a confirmation of their new dreams and good intentions when the daughter swiftly sprang to her feet and stretched her young body.

[Und es war ihnen wie eine Bestätigung ihrer neuen Träume und guten Absichten, als am Ziele ihrer Fahrt die Tochter als erste sich erhob und ihren jungen Körper dehnte.]

Some survive with a young body; others, transformed into vermin, are chucked out with the trash. I admire Bernofsky’s reconstruction of the German here; the good bourgeois phrases ‘new dreams’ and ‘good intentions’ are like parcels which must be gathered up so the sentence’s pronominal passengers can disembark. Irony—gentle yet bitter as the arsenic in the apple—wells up in those pocket-like phrases ‘new dreams’, ‘good intentions’, even ‘their destination’ at which they were so lucky to ‘arrive’. Samsa himself did not enjoy such an arrival, nor did Kafka, nor did the similarly adjudged ‘vermin’ who would undertake train journeys in the horrendous decades to follow. Bernofsky’s athletic limberness, her loops and dives, the closeness with which she rides the subtle curves of Kafka’s sentences and his logics, makes present Kafka’s own virtuosity, so easily grasped in this short, digestible work. Yet the way she, like us, like Samsa’s sister and parents, can pilot away, can spring up from this text, where Samsa could not, calls to mind the precariousness of intimacy, of music, of talent, of communication, of all the little compensations for our verminous human existence.

Read it all at Fanzine.