At The New Yorker: The Medieval Dream Vision of Louise Glück

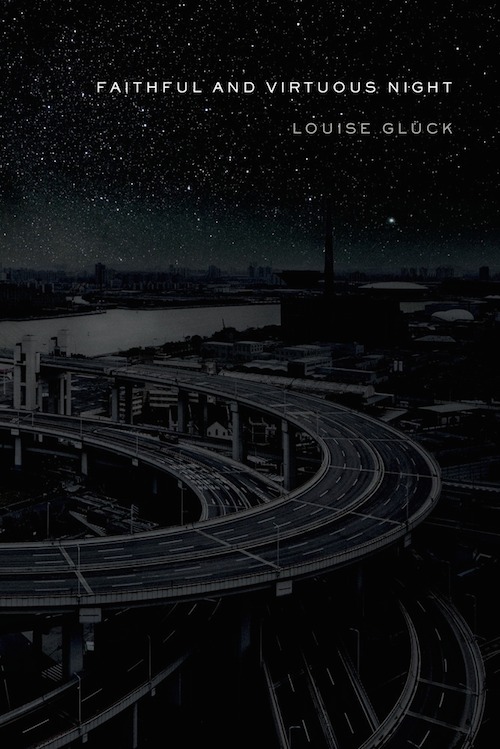

At The New Yorker, a review of Louise Glück's new book (and National Book Award finalist), Faithful and Virtuous Night (FSG 2014), by Dan Chiasson! "From its opening pages, 'Faithful and Virtuous Night' is governed by the logic of medieval dream vision, where the enigmas of the day are not resolved but, rather, reconceived as symbol and allegory," writes Chiasson. You had us at "medieval dream vision." More:

The book ferries between thinking and dreaming, a strait navigable only by poetry, which, even this late in its development, keeps an equal interest in both. The brute facts are, more or less, that Glück is growing old and that her mother has recently died, at the age of a hundred and one. But most of the book happens on the dream side, where a woman orphaned late in life becomes a young, orphaned boy, where to embrace the night is to become a knight, and where to forswear the “amorous adventures / to which I had long been a slave” is to welcome the possibilities that take the place of eros in the “vast territory” of sleep. As in “The Tempest,” old age is greeted here with the rituals of divestiture and abjuration: the occasion for verbal magic is the renunciation of every other kind. First, love goes, and then poetry itself, followed by “various other passions and sensations.” “Each night,” Glück writes, “my heart / protested its future, like a small child being deprived of a favorite toy.”

Glück is not the first writer to figure old age as a second childhood, but the idea has rarely been developed with such eeriness and poignancy. “I never lost my taste for circular voyages,” she writes. Circularity is the theme and the vast aesthetic principle guiding this book; the language is so archetypal and fanciful that we can imagine it in an illuminated manuscript. “Time,” “book,” “night,” “darkness,” “adventure,” and, especially, “stars”: these words occur with chiming regularity, the child’s vocabulary employed to express the deepest secrets of time, like an obituary written in crayon.

The book, or the review anyhow, moves from the child to the parents, as is oft the case...read it all at The New Yorker.