Emily Dickinson, Cannibalizer of Words in Her Lexicon

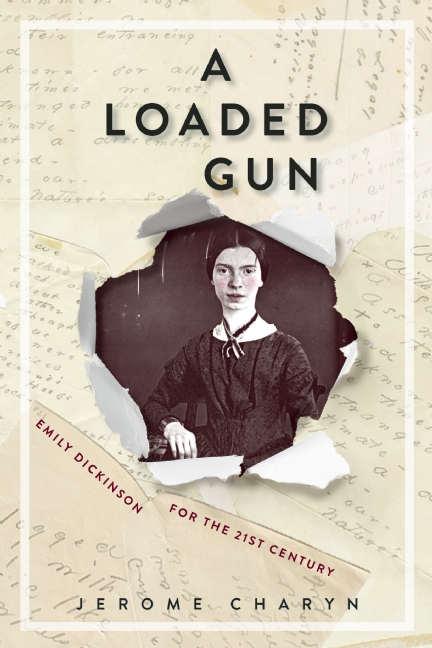

At Longreads, an excerpt from A Loaded Gun (Bellevue Literary Press 2016), by Jerome Charyn, "who writes that Emily Dickinson was not just 'one more madwoman in the attic,' but rather a messianic modernist, a performance artist, a seductress, and 'a woman maddened with rage—against a culture that had no place for a woman with her own fiercely independent mind and will.' ” An inneresting scrap:

Dickinson was reinventing the language of poetry, not by examining poets of the past, but by cannibalizing the words in her Lexicon. Jay Leyda was the only one who understood this. In his introduction to The Years and Hours of Emily Dickinson (1960), he talked about the “omitted center” in her letters and poems—all the tiny ribs of language that were left out. But Leyda was much more optimistic than I am about where those ribs came from. She told riddles: “the deliberate skirting of the obvious— this was the means she used to increase the privacy of her communication; it has also increased our problems in piercing that privacy.” Leyda assumes she always had a reader in mind, that all the missing keys depended upon a specific audience, and that Sue or Austin would know what that “omitted center” was about. Hence he gives us the minutia surrounding Dickinson’s life. And The Years and Hours of Emily Dickinson is a monumental book that reads like a musical composition or collage, filled with every sort of scrap. That sentimental legend of a lovelorn Emily “isolates her—and thus much of her poetry—from the real world. It shows her unaware of community and nation, never seeing anyone, never wearing any color but white, never doing any housework beyond baking batches of cookies for secret delivery to favorite children, and meditating majestically among her flowers.”

Leyda believed that Dickinson was no more isolated from the world than most other artists, that “she wrote more in time, that she was much more involved in the conflicts and tensions of her nation and community, than we have thought.” Yet she remained a riddler, like Leyda himself. Perhaps that’s why he was able to penetrate her personality—crawl right under her skin—before any other critic. It’s difficult to uncover where Leyda was born, or who raised him. Leyda’s “omitted center” is as elusive as Dickinson’s. He still believed that hers was recoverable.

Read the full excerpt at Longreads.