The Rumpus Interviews Ravi Shankar

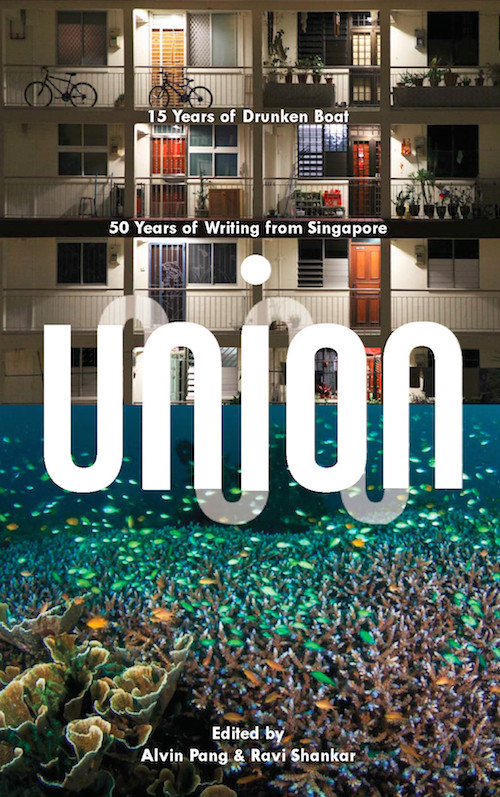

Ravi Shankar is interviewed at The Rumpus! Co-editor, with Alvin Pang in New Haven, of the recent anthology, Union: 15 Years of Drunken Boat, 50 Years of Writing from Singapore (Ethos Books and Drunken Boat, 2015), Shankar talked with Ann Van Buren about how it came to be published; his mother tongue, Tamil (which leads to his next project, Andal: The Autobiography of a Goddess; ekphrastic poetry; and more. An excerpt:

Rumpus: Can you talk about Andal: The Autobiography of a Goddess? You were referring to that earlier.

Shankar: This is a book of translations, and it was also a collaborative project. Priya Sarukkai Chabri is this very interesting Indian poet and novelist (who I met at a festival years ago) who in fact was the first South Asian woman to write a work of science fiction. She wrote this book called Generation 14 but she’s also worked with photographers and dancers, and in fact her sister is a very famous Indian dancer and it so happens that we both speak Tamil, that’s my mother tongue as well. When I was growing up I went to a lot of Hindu temples where much of the liturgy was in Sanskrit. I went to a lot of South Indian weddings and my mother would sing me ancient excerpts from the Vedas. Even when I couldn’t understand it—I don’t really know Sanskrit—I heard the language since I was very young and I feel like it’s almost part of my bloodstream. I almost have a homophonic relationship with the language that has shaped my own music in English in some way. But anyway, Priya and I were talking about South Indian weddings and these Tamilian weddings where they often recite the verses of Andal who is this ninth century Tamil poet/saint. She wrote poems that they still recite today.

Andal composed all of her work before the age of fourteen or fifteen. It was ninth century so life expectancy was different. The other thing about her work is that It’s really sensual and transgressive in a way. She’s a bhakti poet.

In Hindu mythology Krishna was known as the Hindi flute-playing god. Andal is in that tradition, but she’s writing on the precipice of becoming a woman, so her poems are paradoxically very sensual and corporeal and yet what she’s longing for is something transcendent and spiritual. So she basically said she didn’t want to have any mortal lover; she wanted the divine for her lover. She left behind this fascinating body of work. So Priya and I worked together. The work was composed in Chen Tamil, or classical and literary Tamil, which is the equivalent of Old English and even though I speak Tamil, Chen Tamil is a different thing and we had to work with a scholar in South India where these poems are preserved on palm leaves. We did a rudimentary translation and then worked on a colloquial idiom.

The more I learned about Andal, the more I learned that she is worshiped to this very day in India as a goddess. Yet she lived in the ninth century! I won’t go into her life story, although it’s really interesting— but ultimately Priya and I decided to translate her work. This is why people think of her as the South Indian Mirabai.

Are you familiar with Mirabai? She’s a mystic poet from North India and she’s really well known here in part because Robert Bly and Jane Hirshfield wrote a book of translations of her work. Mirabai was very much from the Raj courts, so much of the imagery in her poetry elicit a world of jewelry and diamonds and gold, even though she’s a mystic poet. Andal, on the other hand, comes from this very small village and the legend goes that she was born into the household of this Alvar saint—you know in India, Hinduism is so complicated...