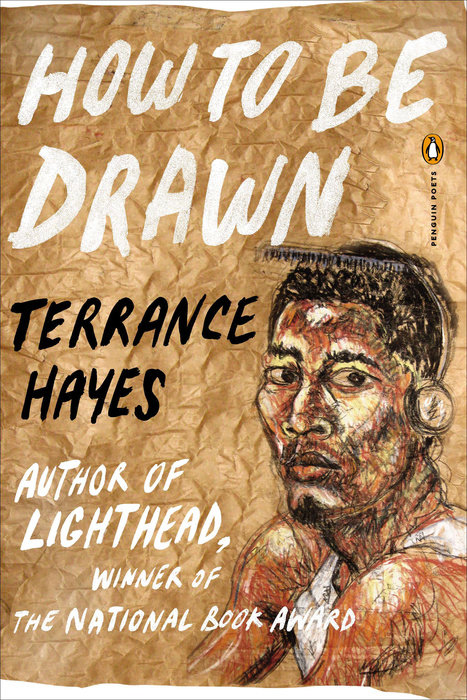

Terrance Hayes's How to Be Drawn Handles One's Ghosts

Terrance Hayes's How to Be Drawn (Penguin Books, 2016) is reviewed by Christopher Spaide for Boston Review. "How to Be Drawn refines, without drastically rewiring, Hayes’s aesthetic, and pursues longstanding obsessions: race and gender performed quietly or extravagantly, absent fathers and emptied masculinities, showboating singers from Orpheus to Marvin Gaye." More:

...Its new questions are how to draw and be drawn by visual arts and stereotypes, how to talk about and to the dead, and how to handle one’s ghosts. Ghosts of a sort have always surrounded Hayes, whose poems make one-way conversation with absent artistic forebears, and with equally intangible family members. But Hayes’s newest poems feature campy, campfire poltergeists alongside the historical haunting of slavery, an aborted child still “pushing a cry out” of its mother next to a séanceful of disagreeable phantoms, all named Vladimir.

Hayes’s suspicious respect for the ghosts orbiting him makes him a terrific poet of ambivalence, of two roads diverging and neither one taken. “I can no longer grasp the logic // Of conflicts,” he admits in “Elegy with Zombies for Life”: “In the pro-life versus pro-choice debate, for instance, / It’s the versus that’s of interest to me.” “Versus,” the political-debate-as-mano-a-mano-boxing-match, is of interest, and so is the very word: more than any living American poet, Hayes is enamored with English’s tiny tokens of qualification, with “or,” “almost,” “maybe,” a “like” that’s both “similar” and “not quite the same,” a “may be” missing the assurance of “is.” He is similarly fluent with repetition and chiasmus, with slight torques of sound that generate upheavals of meaning. (In this transposition of uncertainty into style, and so much else, Hayes’s closest companion is nobody in his own generation but that congenital skeptic, Paul Muldoon.)

A self-professed “gray-area, between-area person,” Hayes invented a style that can air every opinion but support none wholeheartedly, and submit every multifaceted thing, from a word to a metropolis, to scrutiny. In “New York Poem,” Hayes is marooned at a subpar rooftop party in Chinatown, “where there are more miles / of shortcuts and alternate takes than / there are Miles Davis alternate takes,” and where the conversations are just as convoluted. Hayes stands aloofly aside, bottling thoughts: “I am so / fucking vain I cannot believe anyone / is threatened by me. In New York / not everyone is forgiven.” As the poem winds down, as words’ meanings double up and double back, Hayes receives a reassuring reminder that everything can be seen and said anew:

. . . someone is telling me about contranyms, how “cleave” and “cleave” are the same word looking in opposite directions, I now know “bolt” is to lock and “bolt” is to run away. That’s how I think of New York. Someone jonesing for Grace Jones at the party, and someone jonesing for grace.

Read the full review at BR.