At Paris Review Daily, Solmaz Sharif Discusses Gender in Relationship to Warfare, Much More

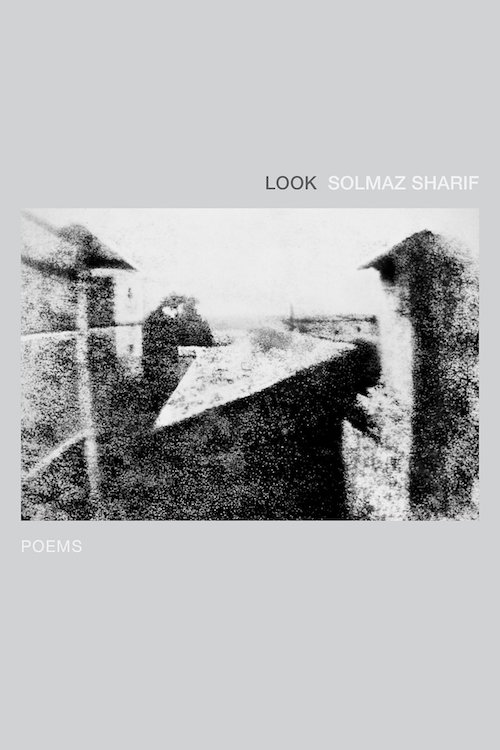

More Solmaz Sharif, this time at Paris Review Daily, where she talks with Zinzi Clemmons about racism, the distinction between poetry and activism, gender and warfare, and her debut collection, Look, which is getting lotsa attention at the moment. "Clichéd, bad writing often means clichéd, bad politics, and vice versa," says Sharif here, responding to a question about politics and aesthetics. More:

INTERVIEWER

Look, to me, has a very female point of view. Women’s relationship to combat—though it’s changing with the evolution of war itself—is usually more oblique. We often play more supportive roles, though our experience is no less devastating. Is there significance to approaching war and surveillance as a woman?

SHARIF

Before I was even a poet, when I studied sociology, what I wanted to look at were media representations of women—Palestinian women in the New York Times, for example. How are women described by media, or by state-sponsored language, in warfare, and how is that representation used to justify state-sponsored violence? Women are often purposefully brought into descriptions of what war is—to justify the rescue of a nation, or to justify its decimation by showing its entire people as despicable or threatening, for example. By default, war seems to be just what happens to men on the front lines, during wartime. The boundaries of warfare—who it affects and who it doesn’t, and for how long—are very much divided along gendered lines, historically. I definitely wanted to challenge those lines.

INTERVIEWER

The book’s power is in its observations of the long-term effects of wars on individuals and families—some of its less-discussed casualties. I think part of the reason you’re able to take this view is because you’re a woman.

SHARIF

I think you’re right. There’s the old personal-is-political adage. But then, to be a woman is also to know that your body and your self and your mind are subject to and delimited by power at every turn, even in your own house, in your own lovemaking. There is no part of your life that has not been somehow violently decided for you by a narrative that was established before you were even born. This is not only true for women, right? It cuts across various identity strata—queerness, race, class, ability, et cetera.

But to have that sense of precarity or vulnerability questioned and challenged by misdirection—for example, when you’re told that you’re overreacting, that what you think is going on isn’t actually happening—this is how the U.S. largely deals with warfare. They say, The war is no longer happening on this block, what are you talking about? That’s something that’s natural to my experience as a woman, and something that seems necessary to expose over and over again. I want to talk about how far-reaching these effects are and how intimate these effects are and how there’s no part of our bodies or desires that are not somehow informed or violated by these atrocities. This is a conversation that began with my own gender.

Audre Lorde’s essay on erotics was a huge influence on me. When she talks about the erotic as a dark feminine power, that’s an argument that could be made here, but I’m not as comfortable making that argument myself anymore. I think all of these questions—what is femininity, what is darkness—and I’m so up in the air about them myself that I don’t really know what to say, other than that I feel, as a person and especially as a woman, that I am under constant threat and attack, and it’s not just me that’s happening to. Somehow, I want the work to show that every time you’re washing the dishes, every shower, every grocery trip—that’s all informed by this violence, whether we’re seeing it or not.

Read more of this great interview at Paris Review Daily.