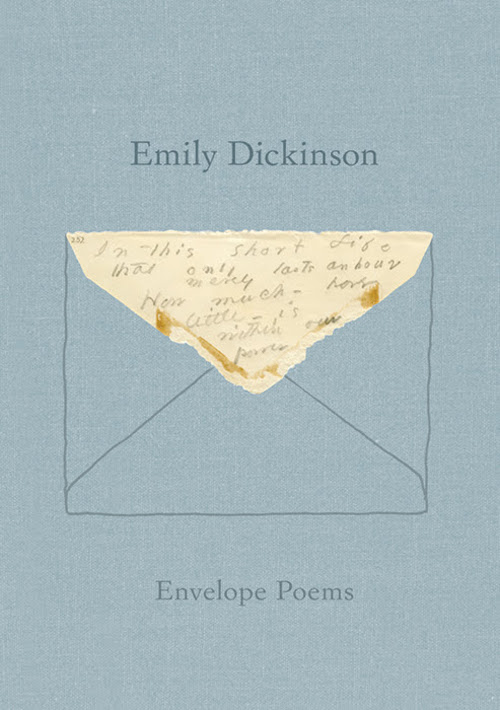

Unfolding the Envelope: A Look Into Emily Dickinson's Scrap Poetry

Anytime is a good time to read some poems by Emily Dickinson, but over at the New Yorker, Dan Chiasson argues that the current moment may be the best time to delve into verse by the Belle of Amherst. Chiasson writes: "This is an extraordinary time to read Dickinson, one of the richest moments since her death. The publication of 'Envelope Poems' and the growing collection of Dickinson’s manuscripts, available online and in inexpensive print editions, coincides with an ambitious restoration of the Dickinson properties in Amherst, including a reconstruction of the poet’s conservatory—a space that was second only to her bedroom in its importance to her art." Chiasson spends time thinking through the fascicles, the envelope poems collected in The Gorgeous Nothings and Envelope Poems, Dickinson's handwriting, and newly available online archives featuring facsimiles of her manuscripts. A brief excerpt for your pleasure:

The envelope poems suggest the current exhilarating paradox of Dickinson’s work: her unique actions of mind are bound in unusually dramatic ways to slips of paper a hundred and fifty years old or more, rarities whose near-perfect reproductions are nevertheless now widely and freely available online. It sometimes feels as though Dickinson’s sojourn in print, so fraught from its inception, was a temporary measure, now nearing its end as it’s replaced by a better technology. To write this paragraph, I looked hard at an envelope: what a mercurial object it is, more like origami than like a sheet of paper. If you use the back of a closed envelope, as Dickinson did in “A 496/497,” you get three squat triangles, like faces of a flattened jewel. She wrote within, and occasionally across, the folds and creases of this complex surface. To read the lines, you have to turn the image counterclockwise. The vertical column of the first panel then becomes a broad horizon, which, when the poet runs out of space, picks up on the third blank panel. The pleasures and the challenges of this kind of reading are impossible to ignore; next to a clear facsimile of these manuscripts, a print version seems, at best, a kind of crude trot. “Letters are sounds we see,” the poet Susan Howe, a major force in Dickinson studies, wrote. Handwritten letters express a far greater variety of sounds than printed ones. And, if the letters are sounds, so, too, are the spaces between the letters, the margins and gaps, the shape and other material aspects of the paper she chose.

There are no masterpieces hidden among the envelope poems, but Dickinson’s incandescent thinking is everywhere on display, and the makeshift nature of the scraps gives us a vivid idea of what composition must have felt like for a woman whose thoughts raced far ahead of her ability to capture them. Who knows how many of Dickinson’s lines were forgotten before the poet had a chance to write them down? Her idiosyncratic punctuation sometimes feels like triage for the emergency conditions of her muse. Her dashes stand for all the nonessential and time-taking aspects of syntax: she is a process poet even in her finished drafts, preserving the urgency of composition. The poems often detail their own state of evanescence: in “A 316,” Dickinson addresses the “sumptuous moment” and entreats it to “Slower go / That I may gloat on thee.” Except that the actual manuscript has multiple anomalies, cross-outs, and alternate words surrounding the lines I have just quoted. The brief “moment” that the poem describes is enacted by the cramped space on which it’s written. Time, on these little scraps, is a function of space: both run out at the same instant.

Head over to the New Yorker now to read in full, including a fantastic look into this old chestnut.