Good Poems About Ugly Things

Is Frederick Seidel an exquisite misogynist?

Introduction

Frederick Seidel. I wonder: Is it all true? I begin to read his Poems 1959–2009, and the first thing I notice is his poetry's dazzling mix of the historical and the individual. Into the emptiness that weighs / More than the universe / Another universe begins / Smaller than the last. The second thing is the vaginas. Or I guess I should say “vaginas,” since Seidel’s women feel less like people and more like abstractions. Nonetheless, the “vaginas” are everywhere: in Seidel’s dreams, in the eyes of a Modigliani subject, on the poet’s motorcycle. All it lacked / Between its wheels was hair. / I don’t care / We do it anyway.—Molly Young on reading Frederick Seidel.

Read the whole article.

Frederick Seidel. I wonder: Is it all true? I begin to read his Poems 1959–2009, and the first thing I notice is his poetry's dazzling mix of the historical and the individual. Into the emptiness that weighs / More than the universe / Another universe begins / Smaller than the last. The second thing is the vaginas. Or I guess I should say “vaginas,” since Seidel’s women feel less like people and more like abstractions. Nonetheless, the “vaginas” are everywhere: in Seidel’s dreams, in the eyes of a Modigliani subject, on the poet’s motorcycle. All it lacked / Between its wheels was hair. / I don’t care / We do it anyway.

Seidel had long been in my mind a figure like Clarice Lispector or Georges Simenon: someone of debated importance whose work I’d failed to investigate for no real reason. There must be a German word for this type of figure. Every reader has his own gallery of them.

Poems 1959–2009 is arranged in reverse chronological order—a decision that squares with the poet’s obsession with aging and deterioration. As the poems grow younger, they become less powerful, less potent, less vehement. They are still these things, but without the full force of Seidel’s maturation. Reading the book is an experience in moving from forte to mezzo, the body’s slowing opposed by the sharpening of Seidel’s mind. The arrangement is a smart idea— what other book progresses in a manner that mimics its primary theme? Act your age! / I don’t have to. I won’t. You can’t make me. I’m in an absolute rage.

Profiling Seidel in April, 2009 for the The New York Times Magazine, Wyatt Mason excerpted a recent poem, “Climbing Everest”—

The young keep getting younger, but the old keep getting younger.

But this young woman is young. We kiss.

It’s almost incest when it gets to this.

This is the consensual, national, metrosexual hunger-for-younger.

and noted that “much of your susceptibility to Seidel’s poetry depends upon how you receive—or are repelled by—such loaded lines.” I don’t speak for all of us in that strange minority of female Seidel readers, but repulsion is not something I particularly feel when absorbing Seidel’s poems. As is usually the case with poetry, one identifies with the voice of the poet rather than with his subjects, and the voice here is all too human. My own poetry I find incomprehensible. / Actually, I have no one. Seidel’s women, on the other hand, feel less like people than like forces reacting to the poems’ speaker. Without feeling empathy for the women of Seidel’s work, it’s hard to take offense at his brutal talk. When it comes to his notorious “I make her oink when we fuck,” there’s simply not a “her” to be offended on behalf of. He might as well be fucking air and making it oink. Which turns out to be quite a feat of willpower and imagination.

I wonder if this is what the crowd of male critics who have been oinking appreciatively since Poems was released last year feel when they read Seidel. The bulk of these admirers seem to me to be smart, youngish city-dwelling men (does Seidel have a rural constituency? Can someone be devoted to both Jim Harrison and Frederick Seidel, or does the sensibility simply halt at the thought?). I have to wonder if some of these men adore Seidel the way their forebears might have adored Henry Miller or Charles Bukowski: as a stylish, debauched avatar to borrow from selectively, but also as a retro figure planted firmly in the past. I remember the vanished days of the great steakhouses. / Before the miniaturization in electronics. / When Robert Wagner was mayor and men ate meat.

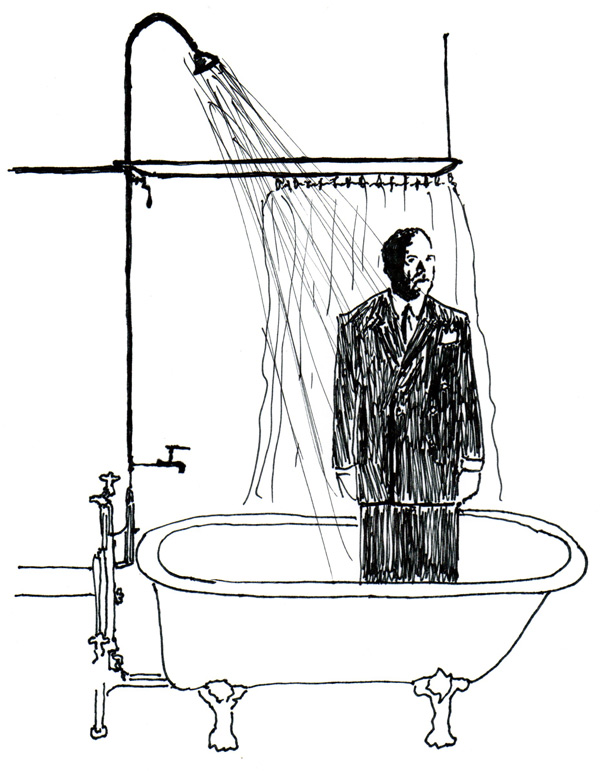

Like that of Miller and Bukowski, Seidel’s style is one of incriminating self-exposure coupled with an exacting (and therefore imitable) aesthetic. But here’s a funny thing. Writing a poem about lust, pride, imprudence—about ordering a call girl or staying at “literally the most expensive hotel in the world” or racing a bike at 200 mph—has a way of neutralizing the unpleasantness of that vice. To write a good poem about an ugly thing, as Seidel does often, is not to write an ugly poem.

Poems 1959–2009 is a book in which it’s not surprising to encounter the words “anus” and “herpes” or “Hadrian” and “Stradivarius.” In other words, it feels like an accurate X-ray of Seidel’s concerns, a suspicion fortified by the comprehensiveness of the collection, which shows Seidel to have the same voice at 29 as he did at 70. Not unchanged, but certainly constant. A large part of this consistency boils down to Seidel’s vigor—sexual vigor, imaginative vigor, an appetite for experience on every part of the globe. And those vaginas.

Seidel is still often miscast as a chauvinist or a perv when what he comes closest to embodying is that bygone type: the rake. He even uses that word to describe himself, along with “heartless” and “dashing,” in “In the Mirror.” These words are used tongue in cheek, of course, but not entirely. It’s never easy to tell when he’s joking. He speaks casually of naked women, war, and Ducati motorcycles, all of which is unsettling to readers who like their “indeterminacy” a little more determined. And then he goes and calls cunnilingus “muff-diving.” Is that horrifying? Or is that funny? If you’d never seen a photograph of the poet in your life—if you closed your eyes and conjured an image—he might look something like Jean-Paul Belmondo or Serge Gainsbourg. Someone filthy-minded and French but with the slightest trace of an American smirk. I want to date-rape life.

Instead of a mindless Dionysus or a guilt-wracked wretch, Seidel often comes across as a man who can’t help thinking cynically about things that might lend a less complicated human an easy pleasure: fucking a younger woman, buying a dozen lilies, wearing a platinum watch. Christian Lorentzen called Seidel’s America “a land of endless delight and unceasing atrocity,” and it is true that the two sensibilities are never far apart for the poet. This is another one of those charms that we enjoy so much in our literary antiheroes, from Philip Marlowe to Jack Kerouac. Perhaps like those men, too, the poet has an unmodern way of seeing people—especially women—that is more a stark beholding than any attempt to empathize. Ah, Tallulah— / Always standing there with her mouth hanging open.

Regardless of whether this is acceptable to the equity-minded modern conscience, the aesthetic consequence is that Seidel’s men and women remain categorically distinct in a way that feels occasionally fierce and occasionally antiquated. The ways in which the sexes relate in his poems are based on the differences between them and not the common ground, the differences that allow them to dance and to mate, both literally and figuratively, without ever fully understanding each other. This may be disheartening for the poetic utopian who balks at conflict, but isn’t conflict one of the endlessly fascinating ways of the world? This is as sensitive as the future gets.

Original illustrations by Paul Killebrew.

Molly Young's writing has appeared in n+1 and the New York Observer.