I Am Not a Medieval Egyptian Hermit but All Work Moves at the Same Speed as if Allowing the Desert to Speak About Lyric Conceptualism and Lisa Robertson

The last possible day! It's wonderful to hear that Lisa Robertson has a new book out, especially if it's one that sheds light on her reading and writing practices. Sina Queyras's most recent post troubles Robertson's logic of the melancholy; and coming out of Night 1 at The Public School/Recess workshop "Dark Nights of the Universe," in which I listened to a paper by Eugene Thacker about the desert called "Remote: The Forgetting of the World" ("At some point, all hermits discover that they have already left") and watched a film co-created by Simon Critchley on the female mystic Marguerite Porete, I'm quite drawn to what Queyras gets to regarding faith being limiting. Normally I'm against intentionality, but that's only in transcategorical art ("let appearance be our guide," wrote Eric Rohmer) and jokes (why do all of Lacan's diagrams of desire resemble the female reproductive system? no really--has this been written about?), and I don't mean to totally decontextualize faith here. But actually Queyras also calls for her reader to "[i]llustrate the mechanism of faith," so why not. Quoting LR first, she writes:

“It (melancholy) is a system that functions to pose a seemingly boundless cognitive space where transformation, never a neutral event, always a grievance or an astonishment, can claim potential…” and later, “melancholics concern themselves with the structure of doubt, rather than the structure of belief, because doubt is inventive. Doubt complicates. Even repudiation is a doubling. In this sense doubt is erotic, as is melancholic space. Doubt, eros, melancholy: affective ornaments” (51).

This is a point of tension for the Lyric Conceptualist though, because it’s hard to believe that belief cannot be inventive…by that logic faith is limiting. Faith, hope, praise become the dead weight of the lyric.

It's true, as Queyras has written in her in-progress manifesto (brave soul), that "Lyric Conceptualism" is not new. But it's clear that something of its sort, a sure poetics, has now been affixed to a vagary that more was going on "out there" (not exactly Baudelaire's "Tout un monde lointain," but close call) than extreme aesthetic/ethical points from which to deliver ourselves. Jean Day and Alan Bernheimer at one time were both described to me as the "lyrical Language poets." And what do we do with Marguerite Duras? I mean, she quoted herself her entire life, writing in ellipses. "You can't like both, Bergman and Dreyer, no, that is impossible," Duras wrote. She preferred Bresson, who I'll get to later. Actually, and this makes sense the more you think about it, Duras really loved Chaplin. "Chaplin's greatness. All by himself, he was the crowd."

I picked up this book called Green Eyes today at Unnameable Books after having coffee with Jean Day, who is in town for a bit, having just read at Bard. She and I were talking about the terrible romantic chemistry Fred Astaire had with Audrey Hepburn (Funny Face!). Jean said, thinking of Daddy Long Legs, "Astaire was his own chemistry." (Look how he imperceptibly turns to exist in his own world next to the astonishing Leslie Caron near the end of this clip.) Chaplin, acting as his own audience, and Astaire, his own partner, had more than grown used to their own images; they were faithful to them. And Duras often sought purity in such a twin, the doubled, then exhumed, the alone, the dead, nothing, non-work, and so on. Also of Chaplin, she wrote: "Drowned as in a bottomless pit. Nothing would stop his fall. The event would drop to the deepest part of him....When the event would come back to him, after some time in him, in forgetfulness, especially in the unintelligible, it's then that Chaplin would recognize it and would make it concrete. Chaplin is not a whole person. He is an inspired cripple, a hiatus of the cinema. He is mentally impoverished" [my italics]. I feel like typing out this entire book to you--she actually calls Chaplin retarded--but I guess that's what paychecks are for (pain for le pain!).

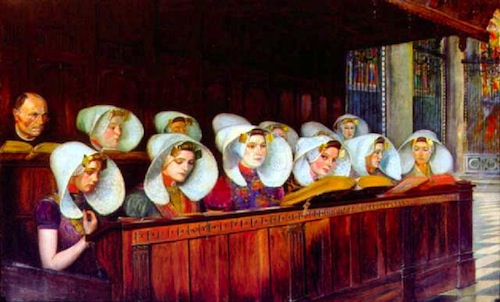

Speaking of pain, Duras was too much of a narcissist to self-annihilate, unless you count her intense alcoholism, but Marguerite Porete was intent on boring a hole in herself ("hacking and hewing" were her preferred verbs) in order for Divine Love to enter--her only answer to the question, How can I will not to will if willing is an expression of sinfulness? But the original state/common human condition might not be sin, someone I would follow everywhere said in our discussion tonight, but poverty. Porete was a member of a tribe of women called the Beguines, from which we derive the word beggar. An annihilation of the soul then begets forms of utopian community.

So so much can be made confluent, can be "found" together to create a constellation of influence, and yes, I'm wary of chain-working, casually picking flowers. But I also see the tyrannical limits of a frame. So just here I am thinking of Anne Carson on Simone Weil in Decreation, Dreyer's Joan of Arc, Duras on the defamiliarizing nature of Bresson, and Jeff Nagy writing for BOMBLOG about Le Diable, Probablement, which I saw alone on Tuesday night ("But later in [Bresson's] life [his Christ-martyrs] became increasingly ambivalent, their martyrdoms more a mulish insistence on their own annihilation than Balthazar’s self-abnegating sacrifice") (PS: cinema as hermitage?). A "mulish insistence on their own annihilation"! Talk about inaccessibility and intimacy at once (Thacker's Remote)! And yet Nagy is right about these nihilistic later "models," as Bresson called his actors. Death drive put in gear by a Godhead working behind one. How many Gods do operate our will to find God. And the film was very of its time (1977); Agnes Varda took it a step further in Vagabond (1985) with the already-dead, wandering Mona.

Duras wrote of her loquacious narrator near the end of "The Painting Exhibition," a story in Writing: "He speaks so that a discomfort will arise, so that deliverance from pain will finally occur." I cannot express to you how pleasing it is for me to arrive at this. It is not transcendence or transformation that is sought or poised for experience, but alleviation. Ha. Transformation might lay claim to potential over melancholy, to go back to Lisa Robertson, but haven't we always, having gotten over the cilice and anorexia mirabilis, wanted to just take a pill? If anything, we can have faith in eventual repose. But "My fidelity is my own disaster," Robertson has also written.

"We are already in the land of melancholy," writes Clint Burnham of Robertson in The Only Poetry That Matters: Reading the Kootenay School of Writing (just out). "That is," he continues, "the pastoral is never anything more than what Robertson calls 'fondly describ[ing]' the land, a 'pining rhetoric [that] points to obsolescence.' The object lacks from the very beginning, and we--as melancholics--misrecognize this lack as loss. The land always lacks, and we only possess its lack through the pastoral, through the signifier of that lack." Or, "The hermit driven to the desert is already occupied by a desertion," said Thacker (also, Vagabond again). Hermits are not empty as in having been emptied, but they are uninhabited to begin with. Forget "I"'s neediness completely, and doubt is inventive, faith delimiting before unlimited, praise (somewhat) undead. This space welcomes affective uselessness. So Lyric Conceptualism at bottom might be too useful (for me), though welcome.